A good friend of mine, who was visiting from Hong Kong, gave me two vials of cologne and a bottle of aftershave. These scented items, which are stocked by the barbershop he patronises, smell so good.

According to the brand literature for this particular line, the fragrance is a “bouquet of tobacco, leather, bay rum, barber’s talc and anise”.

I don’t like the smell of tobacco and anise on their own, and I don’t know what “barber’s talc” is or how it differs from ordinary talc, but in the expert hands of a professional perfumer (known in the industry as a “nose”), they’re all blended together to create an innervating fragrance that cools my skin and uplifts the mood every time I put it on in the morning.

The ancient Chinese used scent in the form of incense, which they burned to perfume interiors and their clothes. People also wore sachets filled with dried pieces of aromatic resins and woods. These scented sachets were usually hung from the belt, looking and smelling sweet.

Liquid perfume, the form with which we are familiar, first appeared in China – at least in Chinese writing – in the year 958 as a gift to the Chinese emperor from Champa, a kingdom located in what is present-day central and southern Vietnam.

A book written in the late 10th century records that the king of Champa sent his envoy to the capital of the Later Zhou dynasty in 958, to present tributary gifts to the emperor.

Available artists: imperial China regulated brothels, Malaysia bars them

Available artists: imperial China regulated brothels, Malaysia bars them

Among the gifts were 15 glass bottles containing liquid infused with the essence of roses. The envoy from Champa said that the sweet-smelling liquid originated from the western regions.

It was noted that when the rosewater was sprinkled on clothing, it not only prevented discolouration, but also gave the clothes an intense fragrance that lingered for a long time.

The “western regions” referred to the Arab world and Persia, where the steam distillation technology for extracting rose oil was mastered by Persian chemists in that period. The rosewater had probably made its way to Champa, a transport hub in Southeast Asia, by way of trade.

In time, this technology of the Islamic world was brought into Guangzhou by Arab merchants in the Song period (960–1279), and adopted by the Chinese. Instead of roses, which weren’t readily available, the Chinese perfume makers used jasmine blossoms.

By the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Chinese perfumers were already blending the oils of jasmine, daisies, hibiscus, and dozens of other flowers to create different perfumes with scent profiles that were more complex and sophisticated.

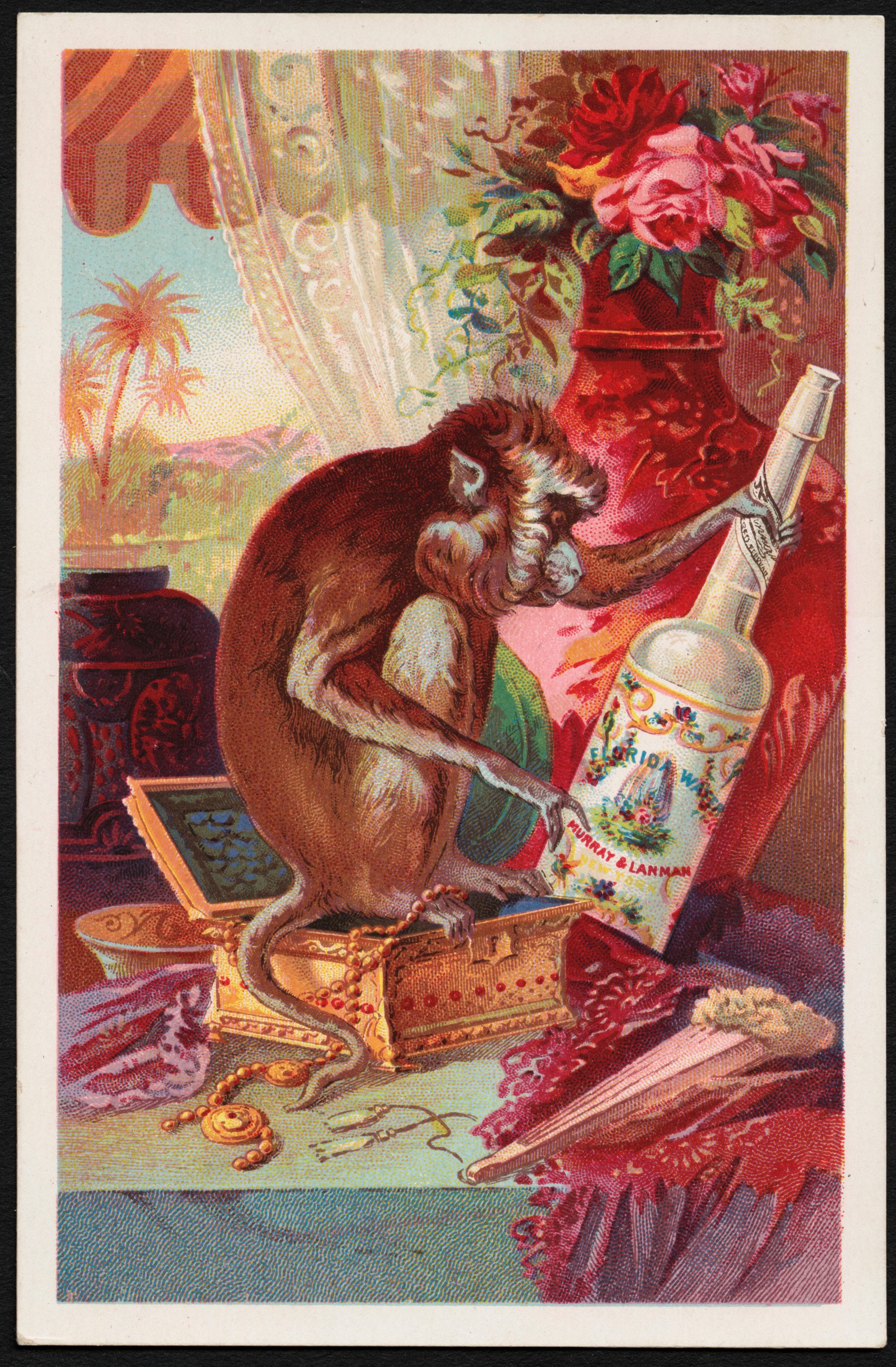

At the turn of the 20th century, inexpensive, mass-produced Florida Water, the American version of Eau de Cologne, became widely available in China. The original formulation created in New York, sold under the brand name Murray & Lanman, was the most popular.

“A light floral scent with lemon overtones, Florida Water cools, cleanses, and calms” says the website of the manufacturer, which is still going strong after more than 200 years.

Murray & Lanman, known as Lin Wen Yan in Mandarin, appears in multiple Chinese works of fiction in the early 20th century.

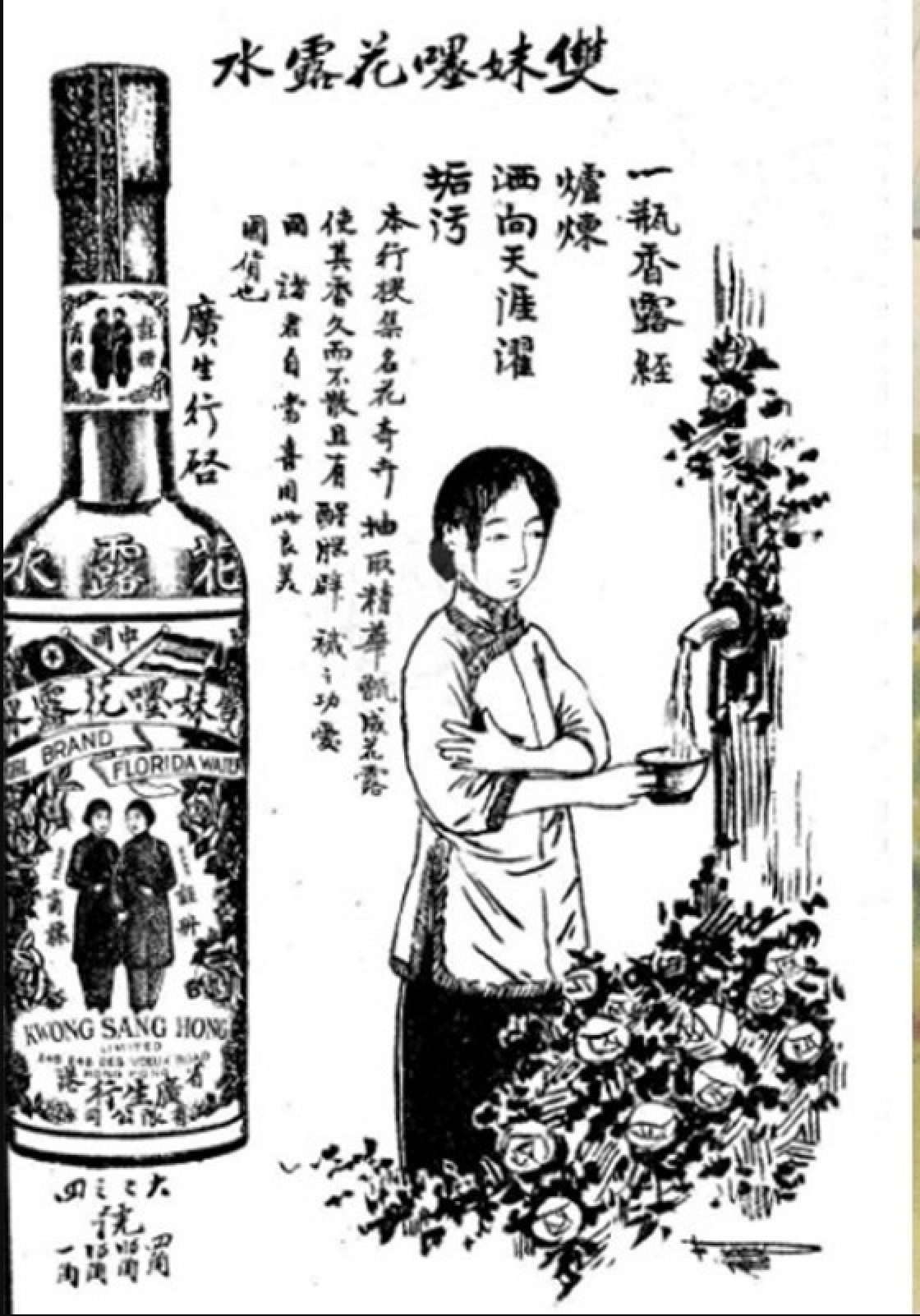

Very soon, Chinese companies were producing their own versions, the most well-known of which was Two Girls Florida Water, created in 1898 in Hong Kong.

The brand has enjoyed a revival of sorts in the past decade or so, and bottles of the vivid yellow juice can be found in shops and even vending machines all over Hong Kong.

They say that smell evokes memories. Every time I wear the barbershop cologne now, I’ll recall the deep conversations, amazing meals and enjoyable moments I’ve had with my friend.

We may not see each other often, but the times we do more than make up for our long absences from each other.