Relations between great powers and their neighbouring regions are often fraught. The cases of the United States and Latin America, or the European Union and North Africa, come to mind.

For instance, tensions related to immigration from Latin America and North Africa, has led to the rise of right-wing populism in the US and Europe, respectively. This has fuelled the rise of populist politicians such as Donald Trump in the US and Marine Le Pen in France.

In China’s case, economic engagement has helped stabilise and strengthen its relationship with Southeast Asian countries, despite ongoing disputes in the South China Sea. One important facet of this engagement is the Belt and Road Initiative, which China launched 11 years ago.

Most of the Southeast Asian countries do not have the means to fund major infrastructure projects, resulting in an infrastructure deficit in the region. Chinese investments, including those of the Belt and Road Initiative, have thus become an important economic force in Southeast Asia. The reality is that very few economies have matched Chinese business groups’ appetite in pushing infrastructure projects, especially capital – and technology-intensive ones, which take a long time to produce returns. While other players have attempted to promote infrastructure building and other forms of cooperation in Southeast Asia, such as the EU’s Global Gateway, there is considerable room for improvement.

By contrast, Chinese firms have managed to deliver some of the most challenging projects in the region. Two recent examples come to mind: the Boten-Vientiane railway in Laos and the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway in Indonesia. The generally positive reception to these projects since their opening has likely increased the appeal of similar initiatives to the public.

Indonesia’s experience in opting for China (over Japan) for its landmark railway project is worth discussing. The Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway was one of the most heavily criticised Chinese projects before and during its construction. Despite some delays and dissenting voices along the way, the project began commercial operations in late 2023. Indonesian President Joko Widodo and Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Pandjaitan are evidently satisfied enough with the project’s outcome to want to continue cooperating with the state-owned China Railway Group Limited to extend the railway service to Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-biggest city.

The Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway has allowed Indonesian policymakers to address long-standing issues, such as the challenging task of setting up development links between Jakarta and smaller urban hubs. And, importantly, working on this project has enhanced the organisational capabilities of the Indonesian central and local governments, which will help them manage other complex undertakings in the future.

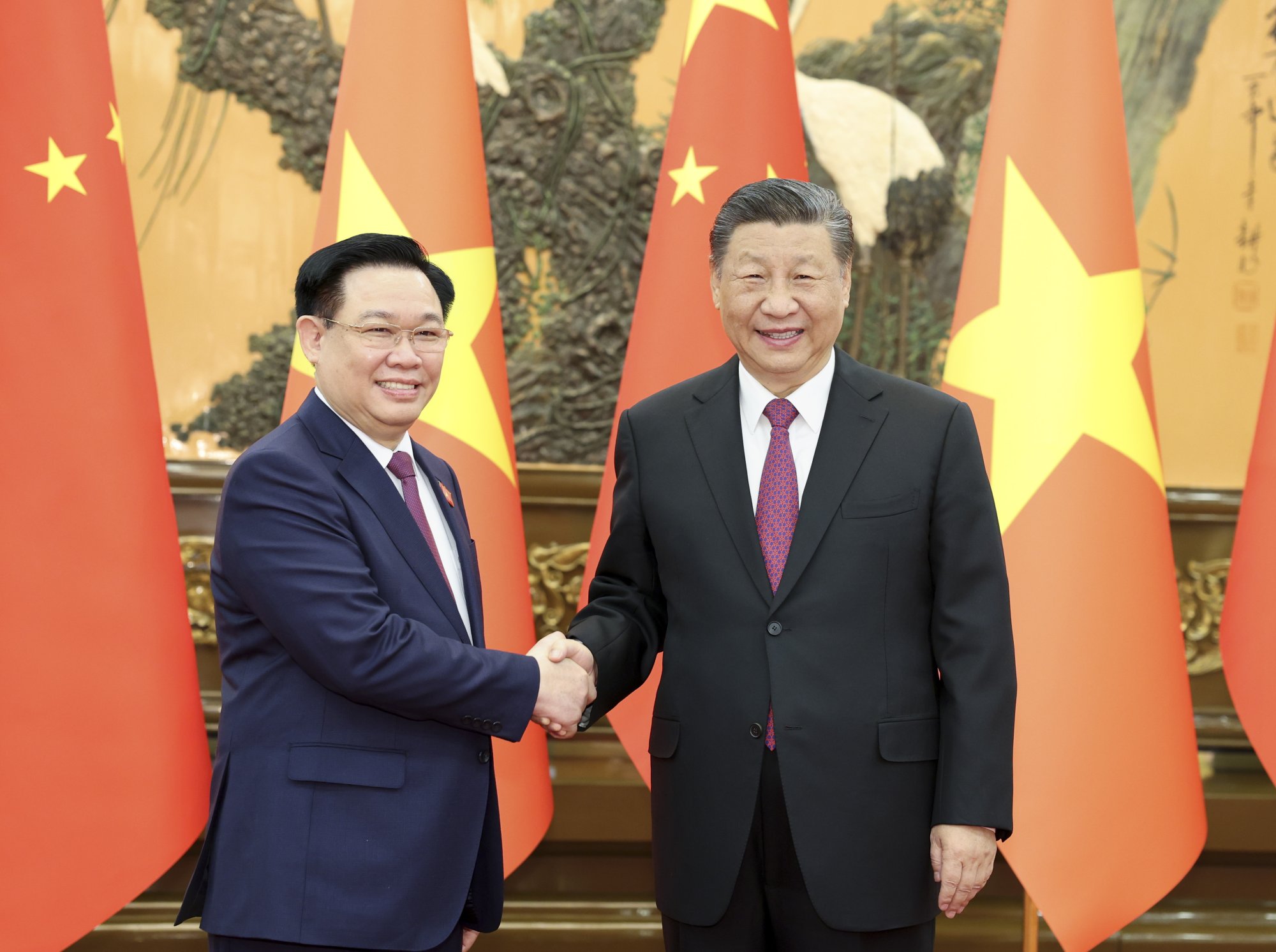

In Vietnam, ties with China have generally been cordial. Notwithstanding reservations in some quarters over the economic domination of China, the reality is a lot more nuanced. For one, Vietnam has harnessed the investment dollars of transnational corporations de-risking from China, transforming itself into a “connector economy” interlinking the US and Chinese markets.

There is another subtext here – the influx of investment and businesses triggered by the US-China competition adds positive momentum to Vietnam’s attempts to continue and even deepen the pro-market reforms it first initiated in 1986. Vietnam and China are currently in the midst of exploring strengthening rail and road infrastructure and connectivity between the Yunnan province in China and Vietnam (including Hanoi and the port city of Haiphong), through the Belt and Road Initiative.

It is true that some of China’s “Going Out” efforts have fallen short of their initial aims. Reasons for this range from political resistance in certain host economies to over-optimistic financial projections. This has led to adjustments, resulting in a shift towards “smaller, greener, and more beautiful” undertakings and projects centred on knowledge and technology, rather than resource- and labour-intensive endeavours.

In addition, ad hoc deals are transitioning towards more institutionalised arrangements, especially after the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) was established in 2018. The CIDCA represents an institutional innovation to harmonise efforts across multiple state organs, with the overarching goal of implementing and overseeing development aid projects more effectively. These transitions, while not usually mentioned in the popular media, underline an important reality of economic cooperation: real and consequential changes often happen slowly and subtly, hidden far in the background.

It is reasonable to expect some occasional pit-stops as the Belt and Road Initiative heads into its second decade in Southeast Asia. The key lies in exploring common platforms to further Southeast Asia-China cooperation. At the same time, it is important to avoid sweeping, oversimplified caricatures of Chinese capital exports. A more balanced perspective, which takes account of context-specific issues in the host economies and the region’s wider economic architecture, would be more fruitful.

Great powers and their neighbours share a common interest in fostering regional peace, prosperity, and political and economic stability. China has been instrumental in meeting the pressing need in Southeast Asia for infrastructure development through the Belt and Road Initiative, and it has in turn reaped political and economic dividends. Economic interdependence has also raised the costs of potential regional conflict. The role of the Belt and Road Initiative in managing the China-Southeast Asia relationship could serve as a valuable model for study for other great power-neighbourhood relations, such as those between the US and Latin America and between the EU and North Africa.