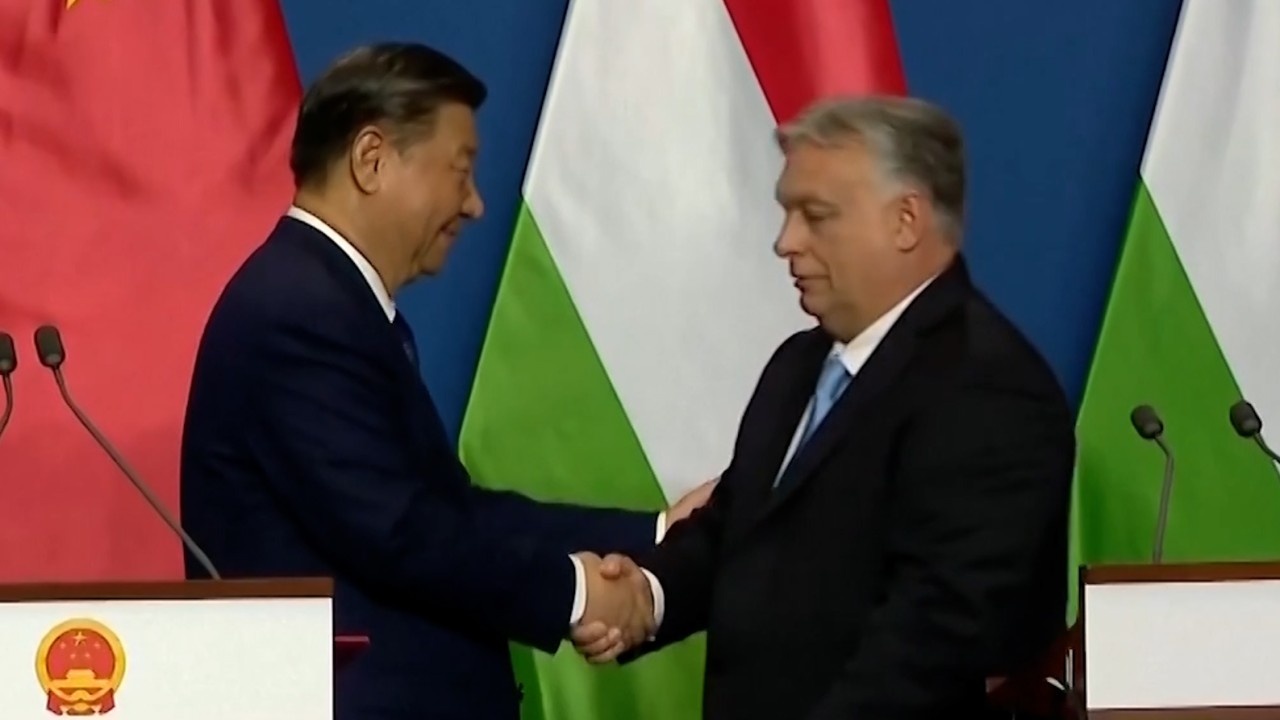

All these developments highlight the strength of an emerging and China-friendly Hungarian-Serbian axis in Europe.

To most European leaders, being endorsed by Orban is not a badge of honour. Indeed, it is seen as something to be avoided as much as possible. By associating closely with Orban, Xi runs the risk of the Hungarian leader’s very poor reputation negatively affecting China’s image in the rest of Europe.

In the medium term, it is questionable whether Orban might really be the best choice for China when it comes to looking for friends in Europe. Sure, things will run smoothly as long as he is in charge in Budapest. But – despite its many serious flaws – Hungary is still a democracy.

Sooner or later, Orban will lose his grip on the political patronage system he has nurtured over the years and the power that comes with it. Any new government taking over from him is likely to be far more liberal and pro-EU. Such a state of affairs would spell trouble for China and also put at great risk the political and economic inroads made so far.

In the long term, there is a risk that China might be overestimating the benefits of the leverage that Beijing is buying in Budapest in terms of its relationship with the EU. While Orban is likely to try and counter any EU foreign policy initiatives that Beijing might view as threatening to its interests or its proxies, a trend is clearly emerging whereby other European capitals are learning to cope with Budapest’s antics.

As work is under way for the EU to shift its foreign policy decision-making process from unanimity to a qualified majority vote, Hungary will eventually be systematically relegated to a losing position within the European Council. Any remaining influence China might have over European foreign policy through the leverage that Beijing holds in Budapest will be lost.

Xi is a master of diplomacy and he handled his trip to Europe extremely well. However, one must question if China’s long-term strategic posture vis-à-vis Europe is the most appropriate. Brussels and most European capitals might very well welcome an enhanced role for Beijing on the global stage and in Europe’s economy.

But by becoming so friendly with the two leaders with possibly the worst reputations in Europe, China risks tarnishing its image in the eyes of the rest of Europe, while reaping economic and political gains that are merely superficial and for the short term.

Matteo Garavoglia is professor of practice and research director of the China-EU Centre at Tsinghua University in Beijing. He is also a senior research associate at the University of Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations