Cultural organisations that brought together otherwise disparate people through similar interests, shared backgrounds and common causes have a long history in Hong Kong. Some organisations flourished and continued for decades while others lasted only a few years.

How these bodies came about, their original aims, the interesting personalities involved over time, and the variegated factors that caused them to eventually vanish, reveal much about Hong Kong society.

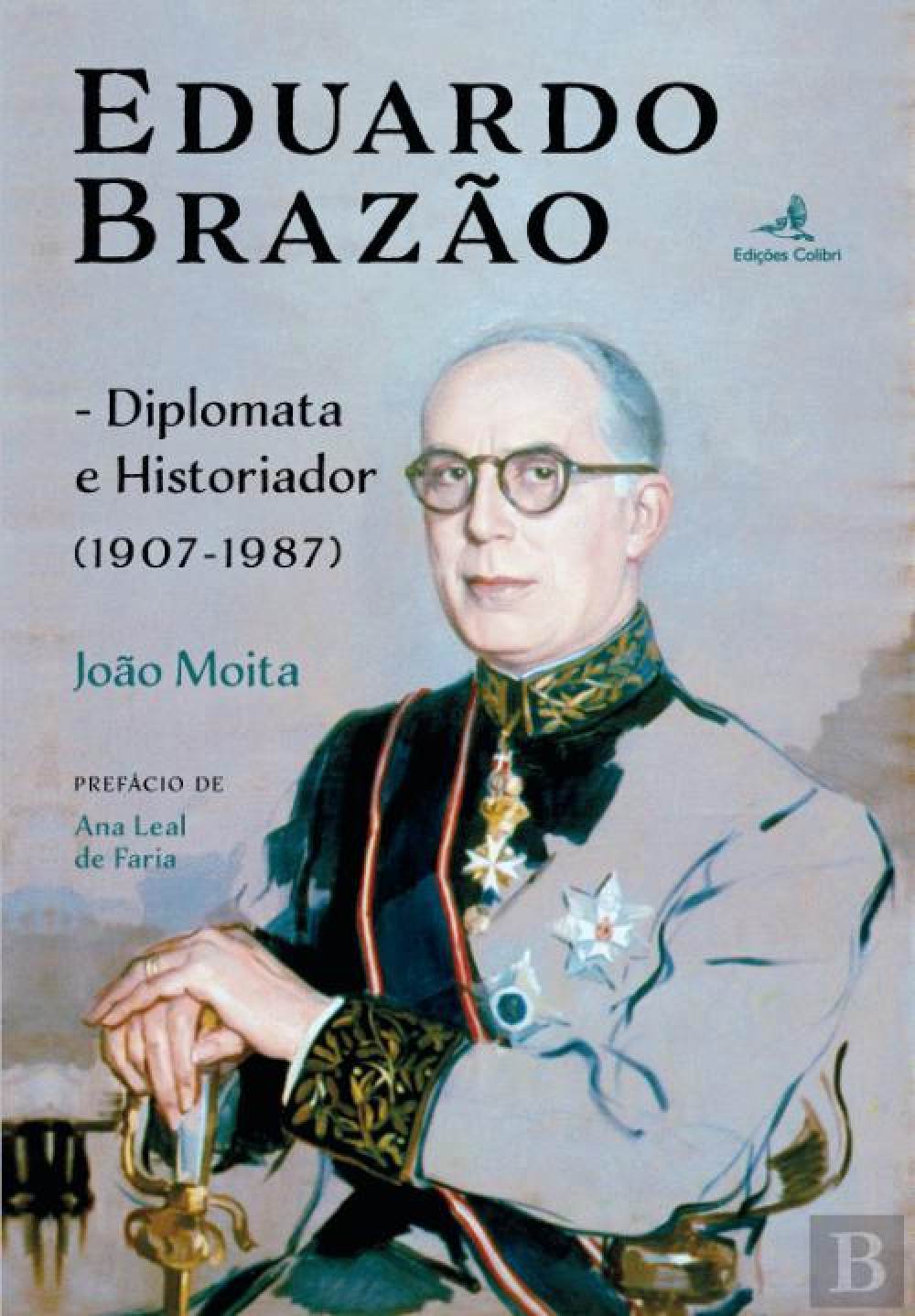

Instituto Português de Hongkong (the Portuguese Institute of Hong Kong), the brainchild of Eduardo Brazão, a particularly farsighted, energetic and scholarly Portuguese consul general, was one such cultural body that briefly flourished from the late 1940s before petering out in the early 50s.

Born in Lisbon in 1907, Brazão was a distinguished career diplomat who was also a trained historian with a keen interest in his subject; he was a member of the Portuguese Academy of History and also the Royal Academy of History in Madrid, Spain.

From his arrival in 1946, Brazão threw himself into the emerging cultural life that marked post-war Hong Kong, largely fomented by the diverse range of people who lived in the British colony after the Chinese civil war.

In Hong Kong, he encountered a large Portuguese community, numbering more than 5,000, whom he described as “descendants of the first Portuguese who had settled in China”.

Through various initiatives, he attempted to encourage these ancestral Portuguese communities to better appreciate and understand themselves and their place in the world.

Brazão’s belief in historical scholarship, which inevitably stripped away centuries of comforting origin myths that served to both divide and unite the local Portuguese, caused periodic friction with others insistent on their own version of events, however self-serving and distant from reality these sometimes were.

He astutely recognised that broad factors of commonality – in particular, aspects of ancestral culture and language – would help facilitate connections with both the British and the Chinese.

His monograph, Portugal and England in China (1947), sets out his viewpoints in characteristically clear-eyed terms.

Unfortunately, Brazão’s enthusiasm for some kind of community renaissance was not widely shared.

Most local Portuguese regarded cultural initiatives with indifference – insofar as they were accorded much attention anyway due to everyday pressures of life in post-war Hong Kong’s overcrowded realities.

Five years of struggles in a terrible climate

His 1951 monograph The Portuguese in Hong Kong, informed by some years of close observation of the local community, was measured but realistic.

Disillusioned by his Hong Kong experiences, as certain tart remarks found within his personal writings suggest, Brazão left Hong Kong in 1951 to become ambassador to Ireland.

On the eve of his departure, the governor, Alexander Grantham, and the local press, showered Brazão with fulsome praise. While he graciously received these accolades with diplomatic aplomb, in a later memoir he dishearteningly described his Hong Kong sojourn as “five years of struggles in a terrible climate”.

While the Instituto Português de Hongkong succumbed soon after his departure, Brazão’s promotion of Things Lusitanian nevertheless had some enduring results.

In 1954, Escola Camões, a Kowloon school intended for the local Portuguese, was initiated with great fanfare. But acceptance into Hong Kong’s more prestigious English-medium schools was always regarded as a pathway for socio-economic advancement – and not instruction in a virtually foreign ancestral language that most local Portuguese were unable to speak beyond basic conversational levels.

From the start, most instruction was in English anyway; before long, Escola Camões had more Chinese and Indian students than Portuguese.

Brazão died in Cascais, Portugal, in 1987. By then, the scenic coastal town near Lisbon had become a retirement bolt-hole for various local Portuguese community figures with whom he had once been acquainted.