Unrealised demand reveals a significant “patient engagement deficit”. Patient engagement refers to the willingness of individuals to collaborate with the healthcare ecosystem to address their needs. Without effective patient engagement, even the most advanced healthcare infrastructure falters and lives slip through the cracks.

Asia is home to more than half of the world’s population. The continent is particularly affected by infectious diseases and non-communicable diseases are rising. There is a need for effective patient engagement, as early intervention can help prevent diseases and greatly affect a person’s quality of life, productivity and life expectancy.

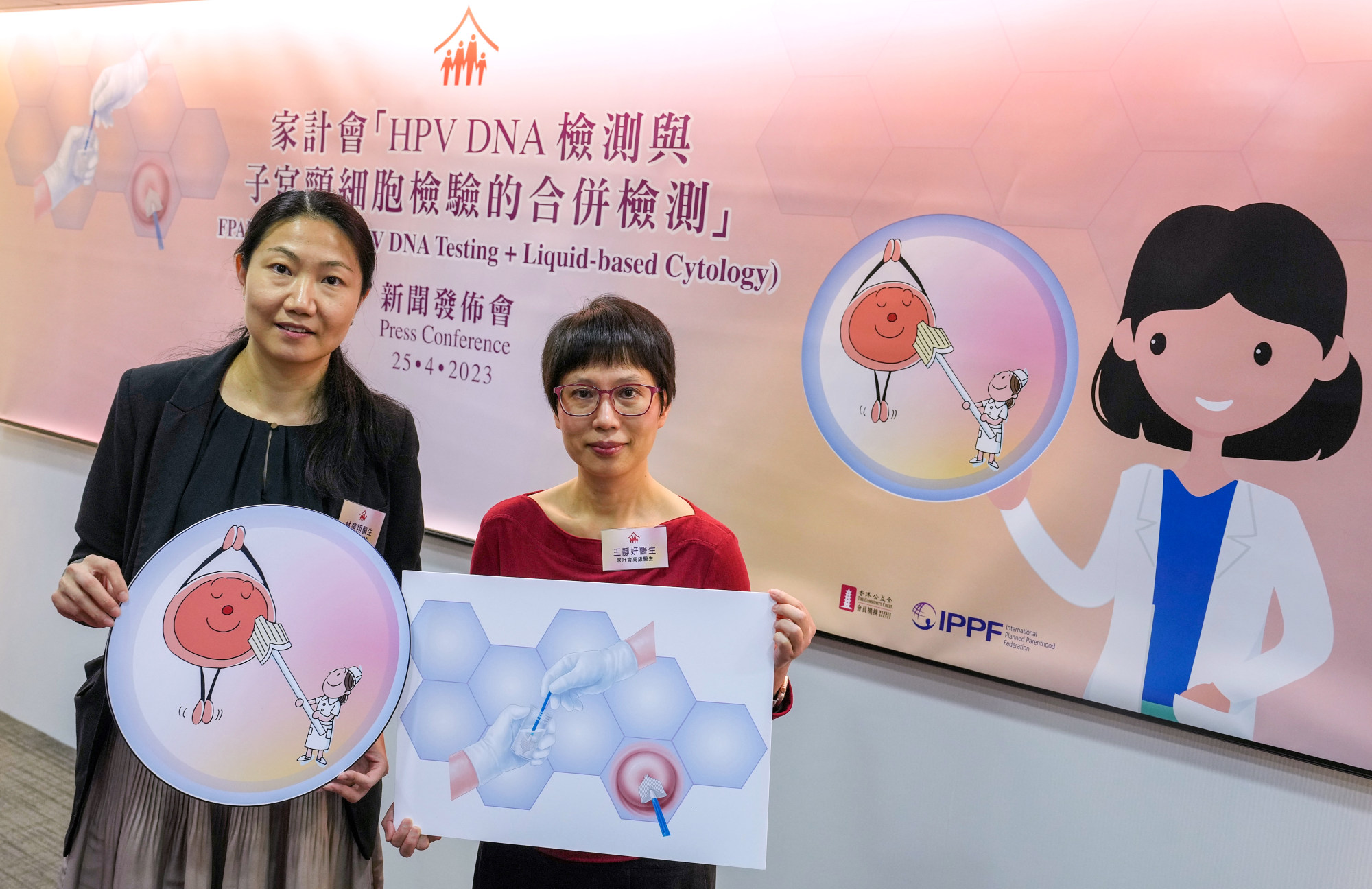

The 2024 Roche Diagnostics Asia Pacific National Women’s Health Survey found that only 22 per cent across Australia, Hong Kong, mainland China, India, Japan, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam feel very knowledgeable about cervical cancer. One in five said they delayed or avoided medical treatment.

Such hesitancy is partly due to women prioritising other responsibilities like childcare, and partly rooted in the belief that undergoing such screening is shameful or embarrassing. That means social stigmas might be keeping millions of women from taking life-saving medical tests.

Cultures in Southeast Asia tend to be more paternalistic and doctor-patient communication is typically one-way, where clinicians provide information on the patient’s health and recommend steps for treatment or monitoring without much consultation or discussion. Over time, this lack of agency results in patients having low curiosity about or a lack of drive to take charge of their health decisions. Patients see their role as passive recipients of care.

Another barrier to effective patient engagement is low health literacy. Studies have shown that many countries across Southeast Asia have limited health literacy, owing to factors such as education, income and socio-economic background.

This knowledge gap is a tangible barrier; it prevents people from taking advantage of the health resources and infrastructure that might exist in their community.

Looking ahead, Asia’s middle class is expected to rise from 2 billion to 3.5 billion in the next five to 10 years. Clinicians should develop more patient-centric modes of communication and processes to allow patients to play a more active role in their health journey. Over time, this creates an environment with more trust and appreciation for proactive and preventive care.

Why free breast cancer screening should be one of John Lee’s priorities

Why free breast cancer screening should be one of John Lee’s priorities

The understanding of how people make their healthcare decisions can go beyond the scientific and commercial to encompass the cultural and behavioural aspects. Addressing unmet healthcare needs across the Asia-Pacific is complicated. With a multitude of factors in play, getting to the root of the issue is anything but straightforward.

The biggest lesson is to understand the diversity of local cultures that shape and drive how people in Asia-Pacific make healthcare-related decisions, and then to develop solutions within these contexts. We can then pave the way for targeted collaborative efforts among healthcare providers, policymakers and communities to bridge the gaps. It takes a global village of passionate players to engage and empower people’s approach to healthcare.

Lance Little is head of region at Roche Diagnostics Asia Pacific