“Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names can never hurt me!” was a trite riposte that – once upon a time – was taught to bullied children, in a misguided attempt to deflect deeply felt pain caused by unwanted personal labels. And being habitually referred to by names not of one’s own choice does hurt.

Some once-ubiquitous racial terms directed at certain ethnic groups, such as Chink (for Chinese), have now become unmentionable and – in some instances – unprintable: one immediately obvious epithet, formerly common parlance in North America, is the now literally life-changingly offensive “N word”.

For many of those whose world view is constructed from politically correct theoretical ideologies, racialist terminology is generally assumed – mistakenly – to be exclusively directed by “white people” against the rest.

Like most easy-to-digest metrics, nuance is lost in the process. But the opposite direction also contains many unattractive epithets.

Jap jung – literally “mixed species” – was formerly a common Cantonese term for Hong Kong’s Eurasian community. “Bastard” was another blunt and – it must be honestly admitted, not always unreasonable – label.

A common assumption was that obviously mixed-race children were illegitimate and thus, by definition, fatherless. In urban Hong Kong’s earliest years, racial mixing and illegitimacy were the same state of affairs, which made the term an accurate, if offensive, observation.

An inherently racist epithet normalised by constant use, gwei (sometimes rendered kwai) literally means “ghost” or “devil”.

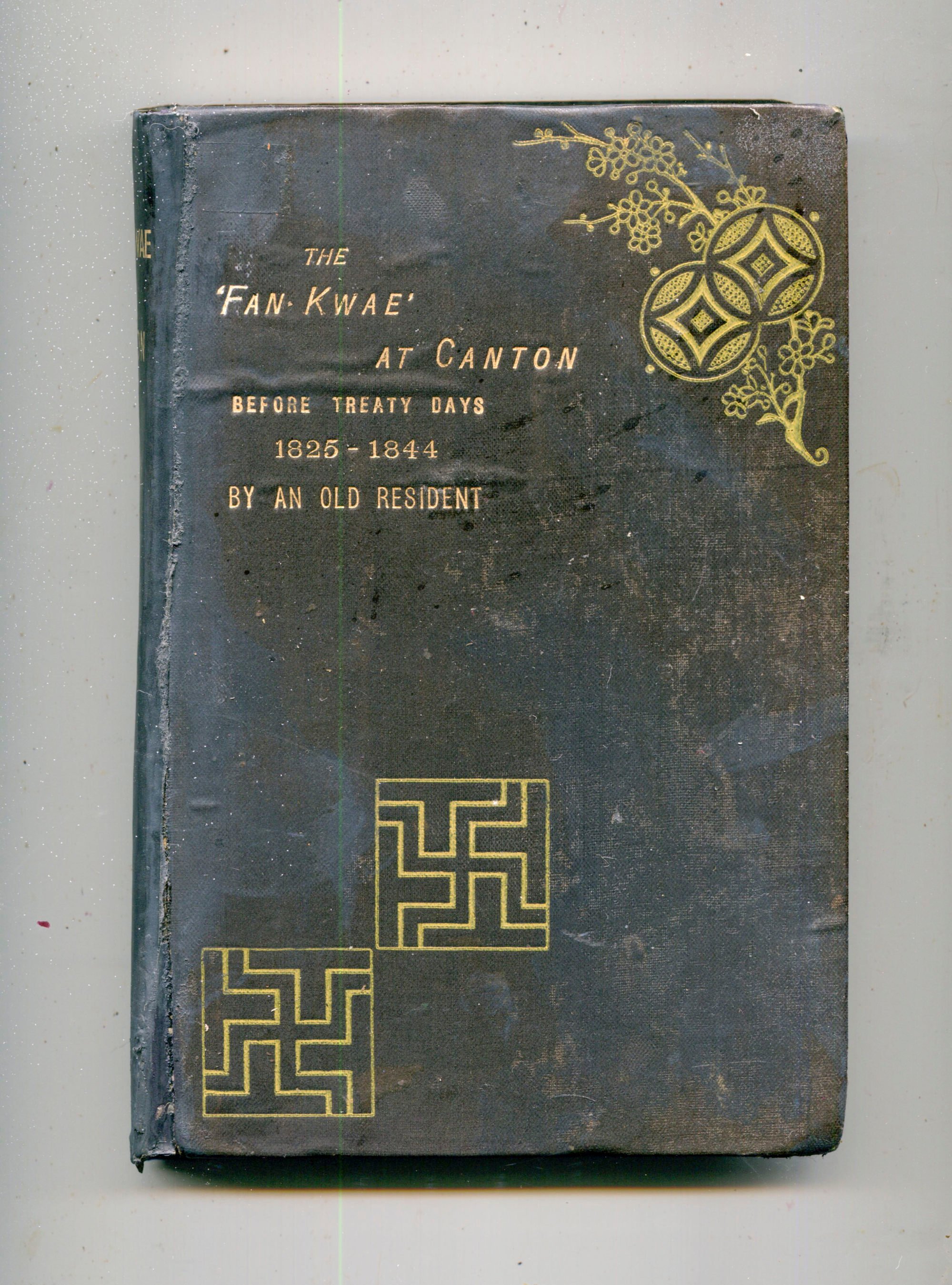

As epithets go, fan kwai (or fan kwae) is older and literally means “foreign devil”. It derives from the (still-standard) Cantonese reference to Chinese as humans and the rest as devils.

Fan kwai – much like gweilo today – was appropriated by long-term European residents and even forms the title of an entertaining, long-ago memoir, The ‘Fan Kwae’ at Canton Before Treaty Days: 1825-1844, published in 1882, by American trader William C. Hunter.

Among the rudest labels were deployed by those of mixed race, either towards Europeans or Asians. Local Portuguese, whether in Macau, Hong Kong, pre-liberation Shanghai or elsewhere on the China coast, referred to Portuguese from Portugal by a number of terms – some more complementary than others.

“Metropolitan” was the preferred polite label – though the Cantonese ngau sook (“cow stink”) predominated among the Macanese. And the Macanese, in the manner of intermediate groups, had preferred names of their own for those they considered generally below them, including os Chinesas (“the Chinese”) and Chino rico (“rich Chinamen”).

In Hong Kong, as elsewhere in pre-liberation China, Eurasians generally referred to Europeans as “the Pures”. An obvious comparative inference from this latter term was that many sadly regarded themselves as “the Tainted”, because of their diluted ethnic origins.

Depending on individual levels of personal confidence that the person using the terms possessed, the label could be ironic, defiant, sneering – or anything in between.

Another touchy term was directed towards those who aspired to European status in colonial and semi-colonial contexts. Those able to successfully palm themselves off as being without Asian ancestry were said to “pass”; those unable to do so ruefully said that they “couldn’t pass”.

On the Indian subcontinent, “half-caste”, along with “blackie-whitie” and “12 annas” (the Indian rupee formerly contained 16 annas, thus 12 annas represented three-quarters of the whole), were commonly deployed by Indians towards Anglo-Indians, as persons of mixed-race there were more politely termed.

In the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia) the mixed-race Indo community referred to those of entirely Dutch origin – or who looked that way – as totok.