Research interests that stretch back over time and space sometimes result in the most unexpected friendships. Enduring affection for Macau, and an abiding enthusiasm for the works of her Vladivostok-born artist father, George Vitalievich Smirnoff, forged a warm, long-term friendship between myself and Irene Smirnoff, mostly conducted by voluminous correspondence.

“In our shared love of the city,” she once wrote, “we found an unusual common bond.”

Part of the White Russian diaspora that settled in China, initially as refugees who fled eastward after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the Smirnoff family first lived in Harbin, in what was then known as Manchuria.

With his mother, George Smirnoff moved to Harbin as a teenager. Later trained as an architect, he designed various buildings, such as the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club premises in Causeway Bay, which still exist today.

Fine art expressed through various mediums remained an abiding love; an early flair for sketching and draughtsmanship carried across into his professional life, while his talent for painting in oils and watercolours was later – quite literally – a life-saving skill.

Irene was born in Harbin in 1934. After some years in Tsingtao (Qingdao), where he established an architectural practice, the family moved to Hong Kong in 1939 to escape the war raging in northern China.

Macao vs Macau: what’s in a name? More than you might think

Macao vs Macau: what’s in a name? More than you might think

“But how was I to guess,” Irene wrote to me once, with characteristic wisecrack humour, “that I would later get the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong for my seventh birthday present!”

Bombed out of their Kowloon home during American air raids in 1944, the family moved to Macau – refugees once more – where Smirnoff painted his famous series of watercolours.

“The year and a half that we spent in Macau during World War II was probably the most peaceful and rewarding period of my father’s life,” Irene recalled. “We had nothing of any material substance. But our family was intact, the people of Macau were wonderful to us and generously gave all kinds of help and support, and we had food on the table every day.”

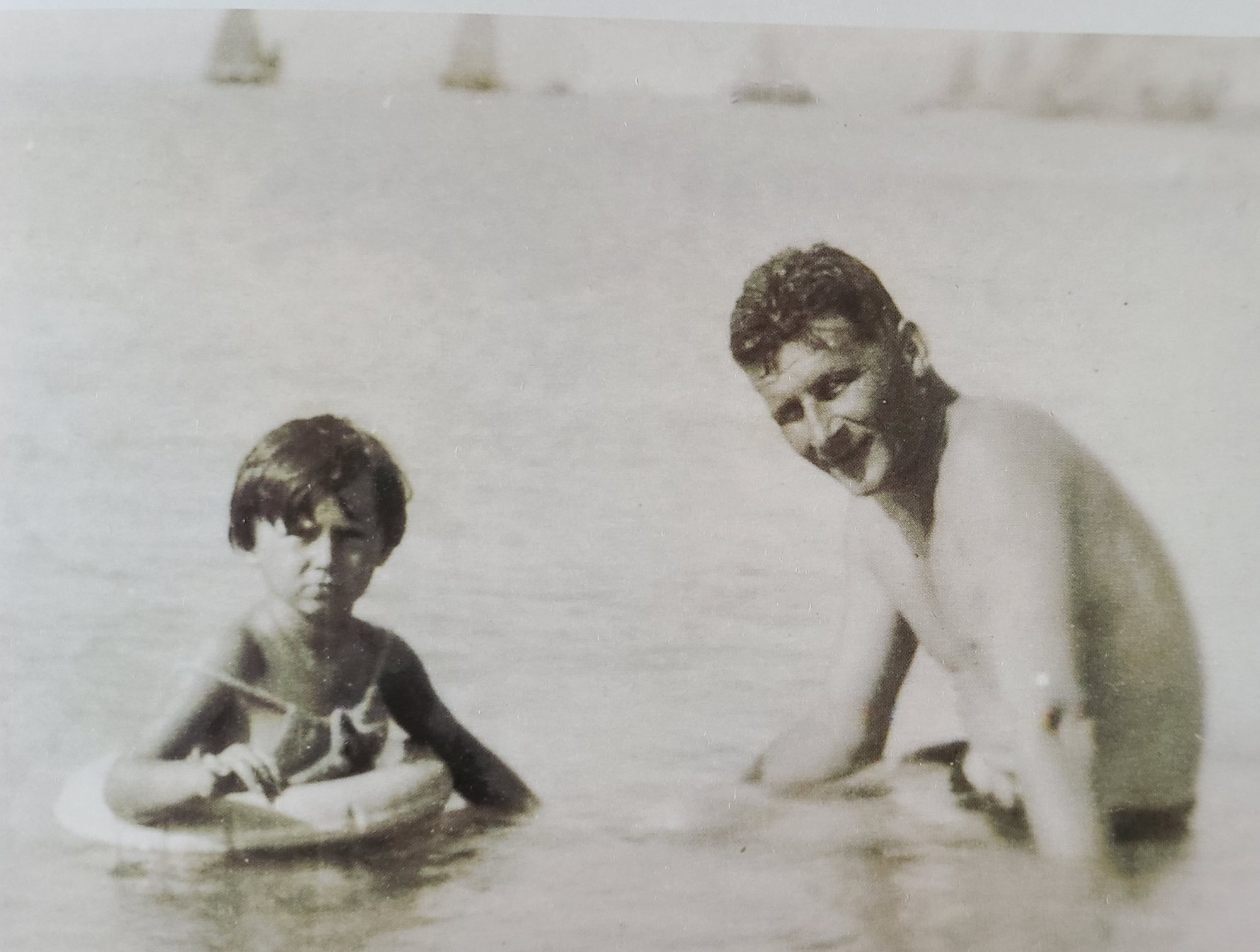

Irene and her father were inseparable.

“He would spend days sketching or painting or staring at scenes he would later depict on paper or board (there was no canvas) or just fishing and thinking,” she recalled. “That dark period, with war always just over the horizon, was almost the only time in his life that my father was truly at peace with himself and his surroundings.

“After our rambles, we would go home, and later that night he would sketch and colour what he had seen earlier that day from memory. If you matched what he painted to the real setting, it was almost like a photograph. I thought that was how every artist and watercolourist worked.”

The family returned to Hong Kong in 1945; George sadly died in 1947, and is buried in the Hong Kong Cemetery in Happy Valley.

Irene left Hong Kong in 1959, worked in England, and later moved to New York. On a return visit to Hong Kong in 2005, we spent a memorably nostalgic day in Macau; Irene hadn’t returned to Patio das Seis Casas (“Courtyard of the Six Houses”), the family’s wartime home, for decades.

Familiar backstreets remained recognisable; Irene even found her way back to her childhood home – literally with her eyes closed.

If anyone knows the history of the Portuguese in Hong Kong, it’s this man

If anyone knows the history of the Portuguese in Hong Kong, it’s this man

“Boys – indulge me!” she laughingly told her husband, Paul, and me, and what had once been a childhood game commenced. “Hold my hands, so I don’t walk into anyone or anything.”

We set off from the bottom step of St Lawrence’s Church, slowly counting our paces, turning right and left, pausing and going on. Eventually, she said we must now be at Patio das Seis Casas, and when Irene opened her eyes, the gateway to their old home was directly in front of us.

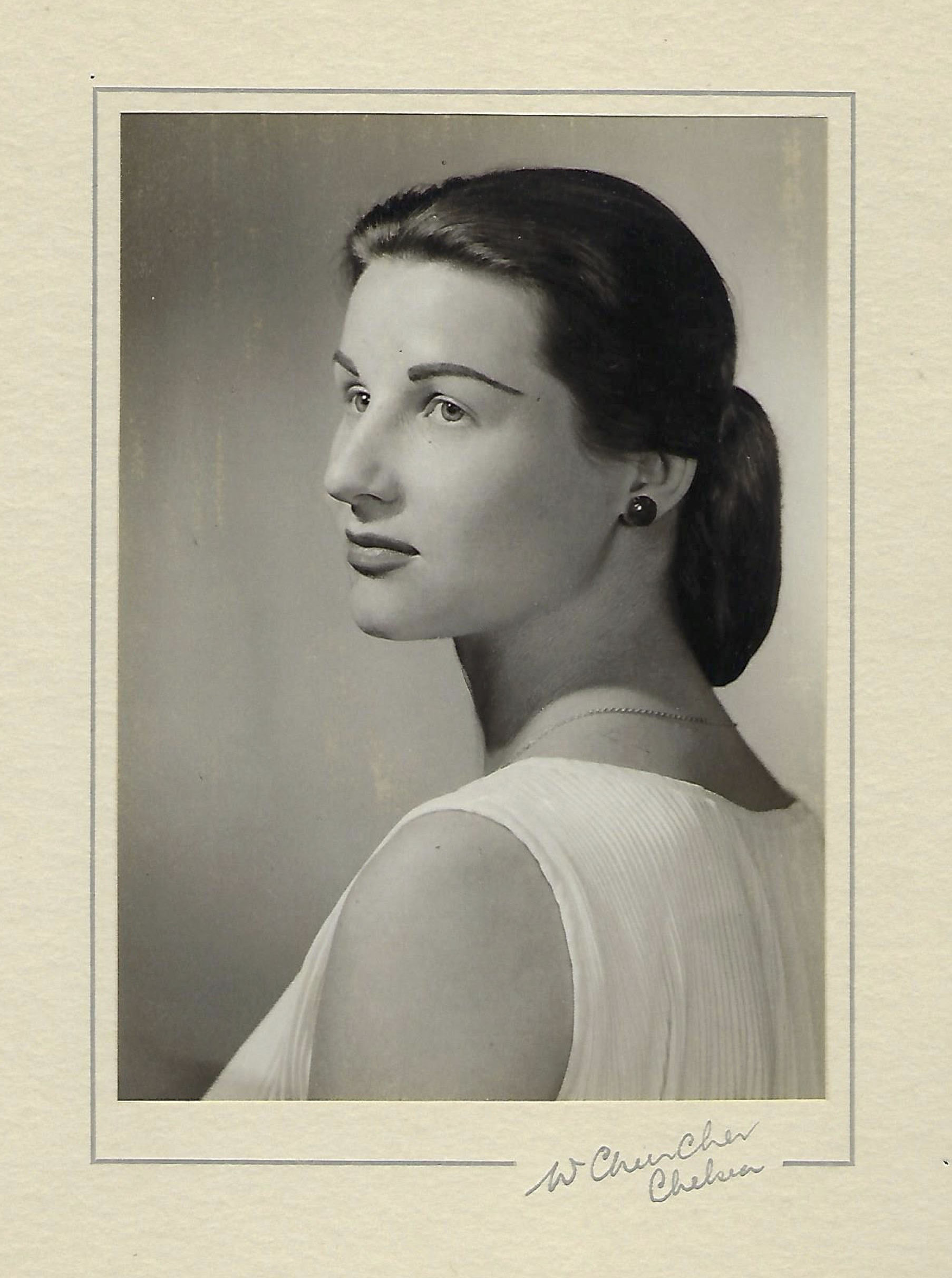

Irene Smirnoff recently died in Florida, just before her 89th birthday.