An initial “zero draft” that circulated more than a year ago now appears to have been diluted, or as the Lancet medical journal notes, “filled with platitudes, caveats and the term ‘where appropriate’.”

In early 2023, the “zero draft” contained details on building an equitable global health security ecosystem. It included recommendations on supply chain resilience for products needed to ensure health security.

But now, with the World Health Assembly meeting just weeks away, differences between the rich Western countries and the developing world seem wider than ever. When the latest round of negotiations ended inconclusively on March 28, the Fox News channel in the United States went on the attack with a story highlighting critics who say the Biden administration was selling out US sovereignty.

The foundation insists the agreement should be rejected in its current draft form, and that even an “improved” draft would need to be submitted to the US Senate for “advice and consent”.

In the US Congress, Brad Wenstrup, the Republican chair of the US House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic, insisted the treaty “must not violate international sovereignty or infringe upon the rights of the American people or the intellectual property of the US”.

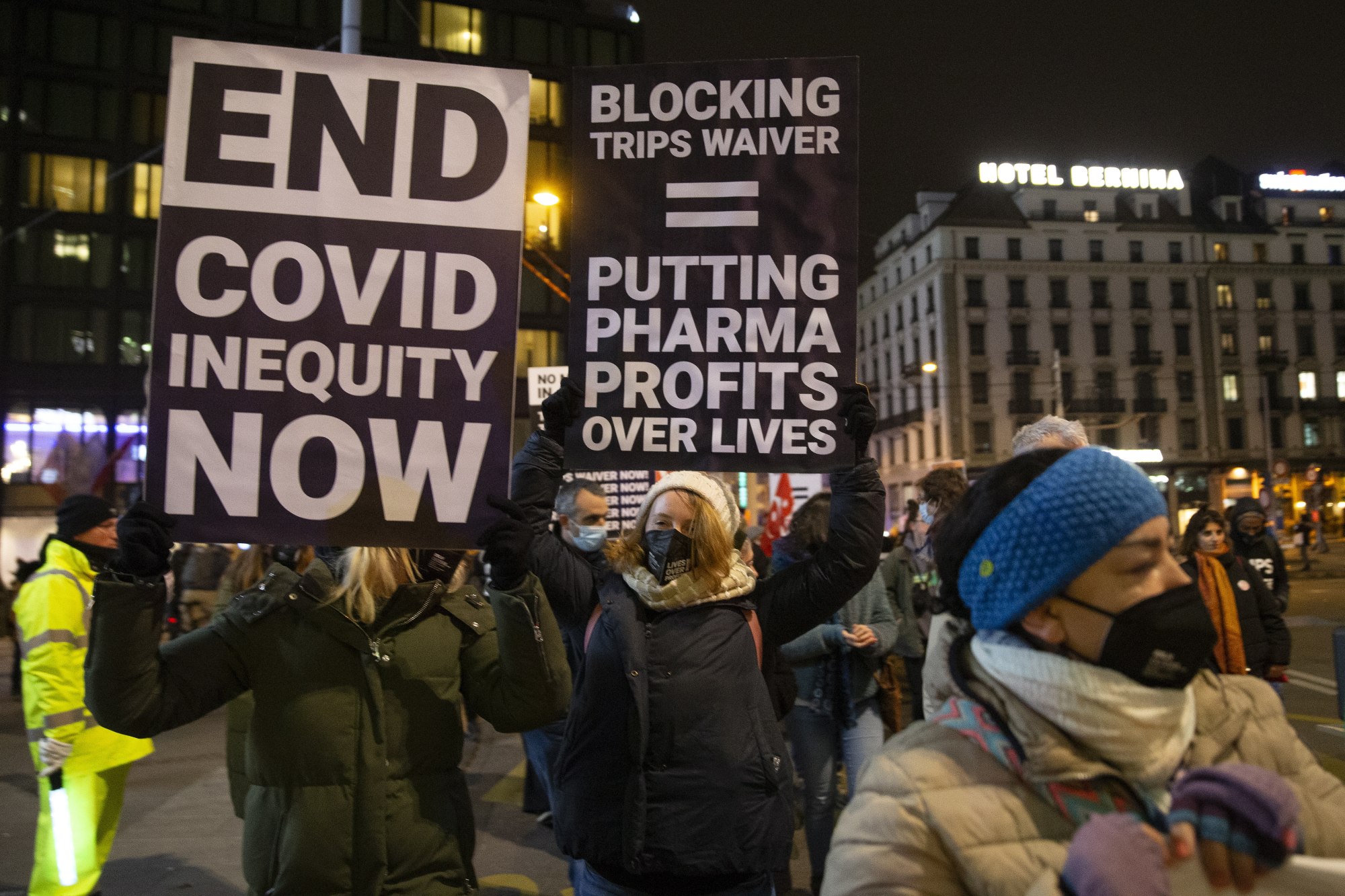

Voicing the concerns of the global science community, a Lancet editorial retorted that such approaches were “shameful, unjust and inequitable”, saying that there is a “need for high-income countries and private companies to behave fairly, [and] that they do not stockpile millions of doses of vaccines or refuse to share life-saving knowledge and products”.

The editorial complained that, under the current draft treaty, the WHO would only have access to 20 per cent of the pandemic-related products for distribution based on public health risks and needs, leaving 80 per cent of medicines and vaccines “prey to the international scramble that in Covid-19 saw vital health technologies sold to the highest bidder”.

Ensuring equitable access “is not an act of kindness or charity”, it insisted: “It is an act of science, an act of security and an act of self-interest … Ultimately it is the politicians of G7 countries who must put aside vested industry interests and finally understand that in a pandemic it is not possible to protect only your own citizens.”

It is of course possible that, by some miracle of pragmatism, a meaningful pandemic treaty will emerge from next month’s World Health Assembly, just as it is possible for China to open its doors to further investigations into the origins of Covid-19, or for the US government to face down the pharmaceutical giants keeping a firm grip on intellectual property rights.

The realist in me says we are likely to emerge with few meaningful protections. As Horton noted a year ago: “Delivering a global agreement on pandemic preparedness and response would be challenging even in the best of circumstances. And today’s fractured and hostile world does not present the best of circumstances.”

Failure to secure an agreement would be a tragedy for which we would pay a terrible price, perhaps dangerously soon.

David Dodwell is CEO of the trade policy and international relations consultancy Strategic Access, focused on developments and challenges facing the Asia-Pacific over the past four decades