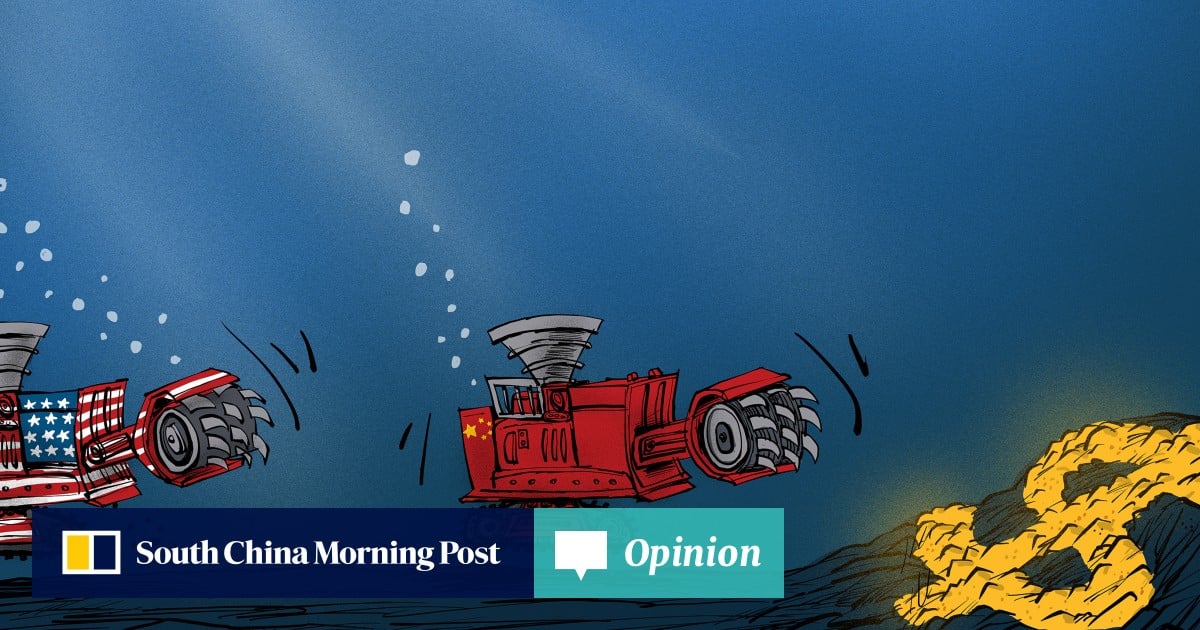

On land, China has used its power to drive mining and build processing infrastructure at a scale and pace unfathomable in Western markets. But polymetallic nodules in the deep sea offer an opportunity to flip this script. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which governs the use of these resources, operates by consensus of 168 countries plus the European Union. This is drastically different from the influence China enjoys on land.

While today, the US does not have voting rights within the ISA, many of its allies do, balancing adversaries on the international scene. By supporting responsible sourcing of these minerals and the means to process them domestically, the US not only can secure its mineral independence, but also uphold robust environmental and labour standards.

The US and its allies need to find new supplies of these minerals and the deep sea floor may provide the answer. The Clarion-Clipperton zone in the Pacific is the main area of economic interest, estimated to hold more cobalt, manganese and nickel than all known land deposits combined.

While the ISA which governs these resources has been successful in issuing and regulating exploration contracts since the early 2000s, mining regulations have yet to be adopted.

With an increased frequency and heightened level of detail in negotiations, the secretary general of the ISA has described commercial mining as “inevitable”. The ISA has defined a road map towards adopting the final code by 2025.

While the US has been on the periphery of deep-sea mining for years, there are promising signs that Washington is moving in the right direction. The ratification of UNCLOS is an essential step, as it would guarantee US membership at the ISA and enable Washington to balance out Beijing’s rule-making position.

Furthermore, the US could sponsor companies to conduct exploration and even mining activities. This past year saw American senators from both sides of the aisle introducing a resolution urging the US to accede to the treaty.

The US could also partner with allies in Europe and the Indo-Pacific region to ensure their views on environmental thresholds and financial aspects are included in the final rules, as well as construct processing infrastructure required to convert deep-sea minerals into high purity products for clean tech and defence manufacturing.

To this end, Congress instructed the US Defence Department to submit a report on the domestic capability of processing minerals on the sea floor. Some companies have expressed interest in locating deep sea mineral refining infrastructure in Texas.

At present, the US stands at a dangerous precipice. China is restricting access to key land-based minerals for defence and green energy technologies, electric vehicles, telecommunications and other essential products.

While deep -sea mining offers a chance for the US and other nations to shore up their supply chains, Beijing is rapidly working to become the first to market, codifying a favourable international regulatory regime. Unless Washington quickly acts to counter China, the US may quickly find itself under water.

James Borton is a non-resident senior fellow at Johns Hopkins/SAIS Foreign Policy Institute and the author of “Dispatches from the South China Sea: Navigating to Common Ground”

David Hessen is managing editor of the South China Sea NewsWire and a recent graduate of the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS)