“In almost pendulum-like fashion, it appears the military has gone from governorship back to guardianship,” wrote expert Aqil Shah in his book The Army and Democracy. The military has justified its interventions by claiming to be saviours against corrupt civilians.

However, the real motive has been to protect the military’s privileged position and massive business interests, estimated to be worth over US$100 billion, or more than a quarter of Pakistan’s gross domestic product.

Khan’s relationship with the generals turned adversarial after he became prime minister and disagreed with them on key domestic and foreign policies. He later claimed he was pressured by then army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa to realign policies as desired by the military brass.

Khan resisted the military’s assertive control and blamed it for conspiring with the US to orchestrate his removal. The incensed military-intelligence complex responded by cutting off his support and building bridges with political opponents instead.

The move to force him into submission backfired badly. Outraged PTI supporters attacked security forces and government buildings after their leader’s arrest.

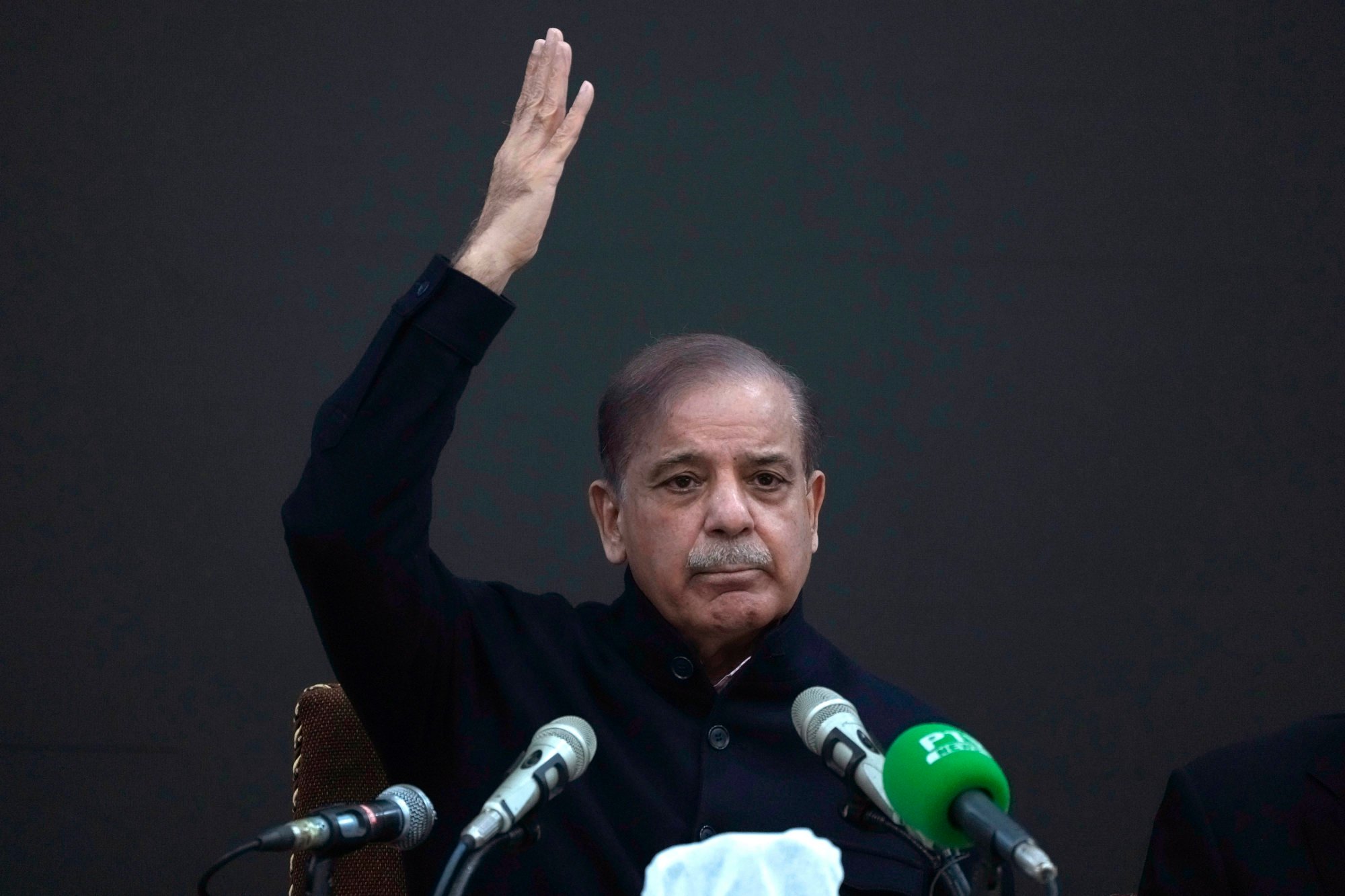

Shehbaz Sharif of the PML-N party is expected to be the nominee for Pakistan’s next prime minister, and backchannel talks are surely under way about cabinet portfolios. This political marriage between unlikely partners is driven by the necessity of keeping Khan out of power. While both parties failed to garner enough seats on their own, together they have the minimum threshold to form a government.

An alliance out of necessity rather than common ideology remains fragile. It will require a careful balancing of competing interests and personalities. The next prime minister will have to accommodate the demands of coalition partners while confronting economic crises. With a razor-thin majority, strains could develop over unpopular decisions, leading to a collapse. Its success largely depends on keeping the military establishment placated while buying time for public support.

Installing an unreliable unity government cooked up through back-door deals would only temporarily paper over the deep schisms of Pakistan’s political landscape. Such a government is unlikely to last long or bring genuine stability. With Khan’s popularity still intact, only free and fair elections conducted under neutral oversight can bring stability in Pakistan’s chaotic environment.

The country today stands at the cusp of a democratic breakthrough – but this will require the all-powerful military taking the historic decision to yield space to civilian supremacy. Whether the military establishment accepts a scaling back of its overreach remains the pivotal question for the country’s future direction.

Allowing civilian supremacy risks diminishing the military’s corporate interests and agenda, while continuing with a controlled democracy is also unsustainable, as evidenced by the mass support that populists like Khan can marshal. The generals have a choice – either recalibrate and let representative politics flourish or risk rebelling against an idea whose time has come.

Professor Syed Munir Khasru is chairman of the international think tank IPA Asia-Pacific, Australia with a presence also in Dhaka, New Delhi, Vienna, Dubai and Mauritius