While this specific factor is usually overlooked, the unexpected gift of abundant spare time – essential to any creative endeavour – allowed unexpected creative energies to flourish.

Along with an astonishing array of special-interest lectures, amateur theatrical performances and musical productions, individual drawing, sketching and painting activities were also encouraged – or at least, not actively prohibited – by the Japanese.

Output varied sharply; pen-and-pencil, caricature-style drawings predominated – maintaining a sense of humour was vital in trying conditions.

80-year riddle of Hong Kong tycoon Paul Chater’s missing art

80-year riddle of Hong Kong tycoon Paul Chater’s missing art

Food was almost always deplorable; rare occasions when special event meals occurred provided inspiration for illustrated or illuminated commemorative menus and souvenir cards, which were made to mark the day. Concert programmes and theatrical set designs were also produced.

Barretto drew his pencil portraits of fellow internees on a pad of Japanese-issued camp letterhead paper; years later, they were disassembled and mounted on card.

In 2015, digital versions of these sketches were displayed as part of a lecture at Club Lusitano, in Central, which movingly brought images of these men, and their half-starved wartime condition, back to life for the first time since Hong Kong’s liberation from the Japanese.

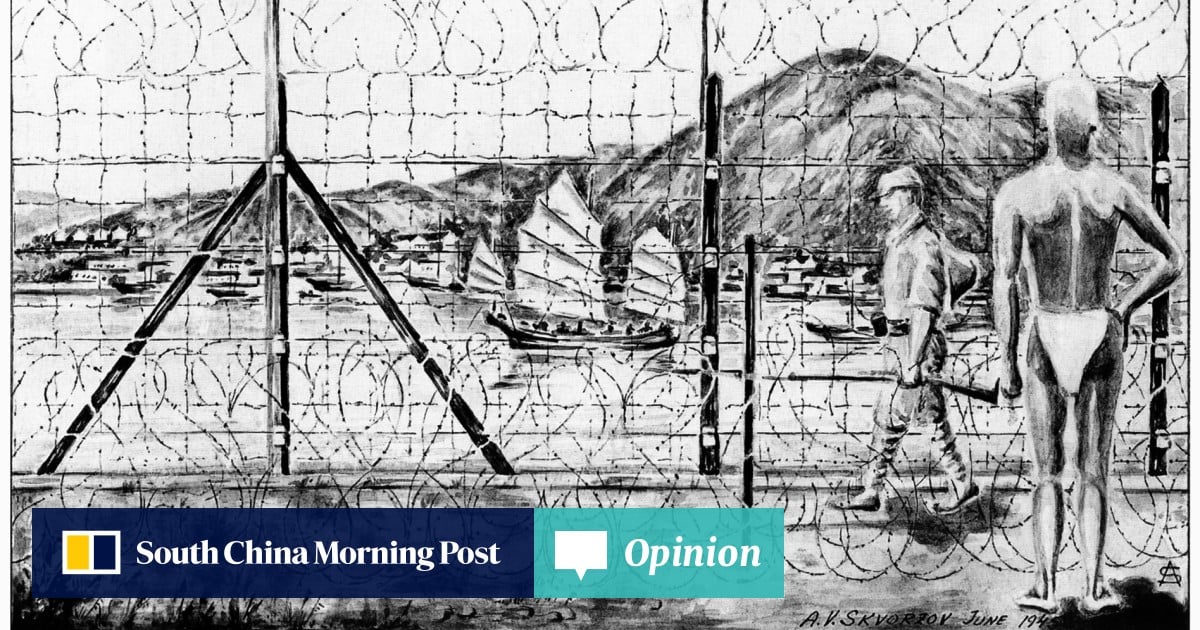

Eurasian Nicholas “Nick” Jaffer obtained a set of Faber-Castell pastels and pencils, which were eked out throughout internment. White Russian architect A. V. Skvorzov’s technical skills saw him portray camp huts and their interiors.

A privately printed post-war folio sketchbook was produced; later expanded to include other sketches, this was published in 2005 as Hong Kong Prisoner Of War Camp Life 25 December, 1941 – 30 August, 1945.

How the Hong Kong School of painting evolved after the Pacific war

How the Hong Kong School of painting evolved after the Pacific war

Many local Portuguese and Eurasian members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC) had wives or other family members who were not interned, and who could obtain art supplies.

Lead and coloured pencils, and watercolours and Chinese brushes, were available in limited quantities throughout the war for those POWs with adequate financial resources.

By 1944, as the tides of war turned steadily against the Japanese, and merchant shipping was sunk in larger numbers, such imported items had become vanishingly scarce and prohibitively expensive.

Some continued their creative pursuits into peacetime. But for most, their prison-camp years remained the only period in their lives with adequate free time and space to create; post-war jobs and family commitments soon pushed their brief artistic flowering into the background.

Uniquely, Barretto’s art evolved from prison-camp pencil sketches to stylised oil portraits, New Territories landscapes and complicated abstract works, but a promising artistic career, which included solo exhibitions, was sadly cut short by his untimely death in 1963, aged 50.

For the other wartime artists, as the years went on, a bundle of yellowing sketches drawn on camp letterhead paper, kept safely tucked away in a desk drawer, or a few brightly coloured sketchbooks brought out from time to time as conversation pieces at camp reunions, were all that marked this brief explosion of long-ago creative endeavour.

In the course of time, some artworks were donated to museums here and elsewhere; Britain, Canada and Australia are the main archival repositories of the city’s POW camp artwork outside Hong Kong.