It is crucial, however, to assess the new faces who have been recently promoted to the Politburo and Secretariat, the most consequential political agencies in the one-party state. Given the timing of the appointments as well as their criteria, they are likely to remain at the top echelon of the nation’s leadership after the 14th Congress in 2026.

At the CPV’s 9th plenum on May 16, four new Politburo members were elected to replace the six leaders ousted since 2021. They were Le Minh Hung, former CPV Central Committee chief of staff; Bui Thi Minh Hoai, Central Mass Mobilisation Commission head; Do Van Chien, Vietnamese Fatherland Front chairman; and Nguyen Trong Nghia, Central Propaganda Commission head. Vice-minister of Public Security Luong Tam Quang was chosen to head the Ministry of Public Security, a Politburo-level position, suggesting his imminent promotion to the key policymaking body.

The CPV Secretariat, which manages daily party affairs, also saw a restructuring at the top. General Luong Cuong, the head of the General Politics Department of the Vietnam People’s Army, succeeded Truong Thi Mai as the new permanent member of the Secretariat. General Trinh Van Quyet replaced Cuong, making him eligible to join the Secretariat. These reshuffles significantly boost the army’s presence in the CPV’s top institutions, with three Politburo members (Luong Cuong, Nguyen Trong Nghia and Minister of Defence Phan Van Giang) and two Secretariat members (Trinh Van Quyet and Nguyen Trong Nghia, who holds this position concurrently with his Politburo role). This will help balance the power against the public security apparatus, which is dominant in the elite institutions. In another notable promotion, Vice-Minister of Public Security Nguyen Duy Ngoc has become the CPV Central Committee’s chief of staff. This hints at his likely elevation to the Secretariat soon.

While further additions might follow, such as the promotions of a new vice-prime minister and the National Assembly’s vice-chair, the latest appointments have filled nearly all vacancies left by the leaders purged in the anti-corruption campaign. The moves have stabilised the political system after a period of turbulence ahead of the party congress that will pave the way for a new leadership transition.

A noticeable trait among these seven new leaders is their background in either the party apparatus or the police and military. Only Le Minh Hung, former governor of the State Bank of Vietnam, qualifies as a technocrat (someone with technical or economic expertise). This makes two technocrats, along with Hanoi’s party secretary Dinh Tien Dung, out of 16 Politburo members, compared to seven out of 16 at the 12th Congress in 2016 and five out of 19 at the start of the 13th Congress in 2021. This is the lowest ratio of technocrats in the Politburo since 1997. The party often follows the principle of vừa hồng vừa chuyên (“both red and expert”) when selecting leaders – meaning they must demonstrate commitment to communist ideology as well as technical expertise. However, the emphasis has now decisively shifted more towards ideological purity.

Second, the CPV appears to be rebalancing regional and gender representation in its top ranks, evident in the promotion of a woman member (Bui Thi Minh Hoai), an ethnic minority member (Do Van Chien), and a Southerner (General Nguyen Trong Nghia). This effort suggests a desire to maintain certain norms despite recent disruptions.

Third, the ascent of Generals Luong Tam Quang and Nguyen Duy Ngoc, long-time aides of President To Lam at the public security ministry, are significant. In a sense, both are “special” cases, as they do not meet the formal criteria for promotion, which requires them being at least full-term Central Committee delegates. Even more strikingly, the duo were among the “exemptions” in the 13th Congress when first elected to the committee in 2021, being over the age limit for first-time members. Along with General Vu Hong Van’s elevation to the Central Inspection Commission last November, these moves suggest To Lam is consolidating power within the party-state system, potentially positioning himself for the general secretary role in 2026.

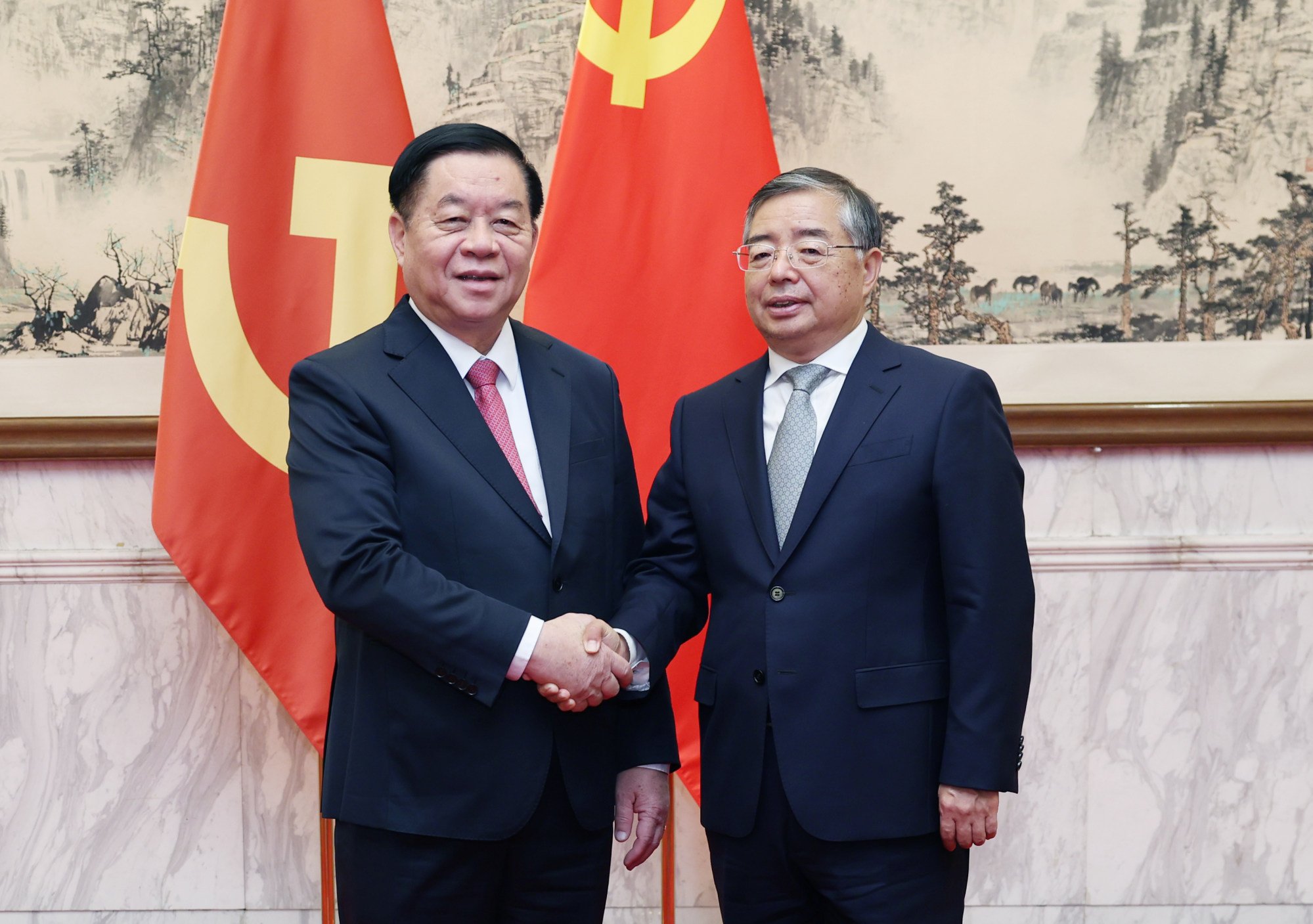

Though the full impact of these personnel changes remains to be seen, significant shifts in Vietnam’s economic governance or foreign policy are unlikely. Performance-based legitimacy will continue to underpin the regime’s stability, while trade openness, ideological considerations, and China wariness will sustain Hanoi’s “bamboo diplomacy” with Beijing and the United States.

However, the diminished technocratic expertise among top leaders raises concerns about Vietnam’s capacity to tackle multifaceted challenges, including economic issues, the energy transition and foreign policy. Additionally, the new leaders, barring the two vice-ministers of public security, are more “thinkers” than “doers,” lacking significant achievements that justify their promotions. This reinforces the belief that in the uncertain context of the anti-corruption campaign, it is wiser for bureaucrats to play safe by doing less and survive rather than taking risks. This hardly encourages cadres to “dare to think and dare to work” to solve the current bureaucratic paralysis. The term was coined by General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong to protect and motivate party workers.

On a positive note, the mass elevations might signal a reduction in internal infighting as multiple factions settle their differences. With two years until the next party congress, To Lam appears to have emerged as the ultimate winner in the fiercest game of thrones in the CPV’s recent history. While the long-term trajectory of Vietnam remains uncertain, this new-found stability might provide a respite after years of turbulence at the top. This would help prepare the party for the coming leadership transition.