On Thursday, one of Duterte’s most trusted police officers, Police Colonel Richard Bad-ang, was removed from post as Davao City police chief. The next day, 34 other police officers, including six station commanders, were removed from their posts, according to Davao City mayor Sebastian “Baste” Duterte, the youngest son of the former president.

The officers have been suspended from duty and are under investigation for the deaths of seven suspected drug dealers killed in buy-bust operations after Bad-ang’s appointment on March 22. The 36-year-old mayor had declared a drug war that same day and warned, “If you don’t stop, if you don’t leave, I will kill you.”

“As far as the Dutertes are concerned, all destabilisation and ouster options are on the table such as people power, withdrawal of support, coup d’etat, rebellion, secession, impeachment and even assassination,” former senator Antonio Trillanes IV told This Week in Asia on Monday.

News reports said two battalions of police Special Action Forces, under the command of the Philippine National Police (PNP), also arrived in Davao City at about the same time the officers were relieved of their duties.

Duterte cultivated close personal relationships with the police force of Davao during his 22 years he served as its mayor. When he became president from 2016-22, he appointed trusted Davao officers to senior positions in the PNP, including Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa as its head and others as police station chiefs in Metro Manila and elsewhere, to carry out his operations against illegal drug users and dealers.

Davao City mayor Duterte “condemned” the police officers’ removal as “an abuse of power from higher authorities” in a statement on Sunday. He pointed out that the law gave him “operational supervision and control” over the city police.

He said the police under Bad-ang had dramatically reduced the city’s crime rate and “there is substantial evidence supporting the assertion that the buy-bust operations were conducted within the bounds of the law. Any insinuation of misconduct on their part is unfounded and unjust”.

Trillanes said the latest developments did not surprise him. “I believe [their mass removal] is more of a pre-emptive action for the imminent ICC arrest warrant [for Duterte].”

During a press conference on May 7, the former senator said he expected the ICC prosecutor to issue such a warrant, possibly in June or July. He warned that “there are active and retired PNP officials identified as involved in destabilisation efforts”.

Responding to the allegation, Harry Roque, a former spokesman for Duterte, told the media that Trillanes was having “hallucinations and hangover from his coup d’etat days”.

The PNP also rebutted Trillanes, saying it had not come across any such destabilisation plot and urged him to not politicise the police force.

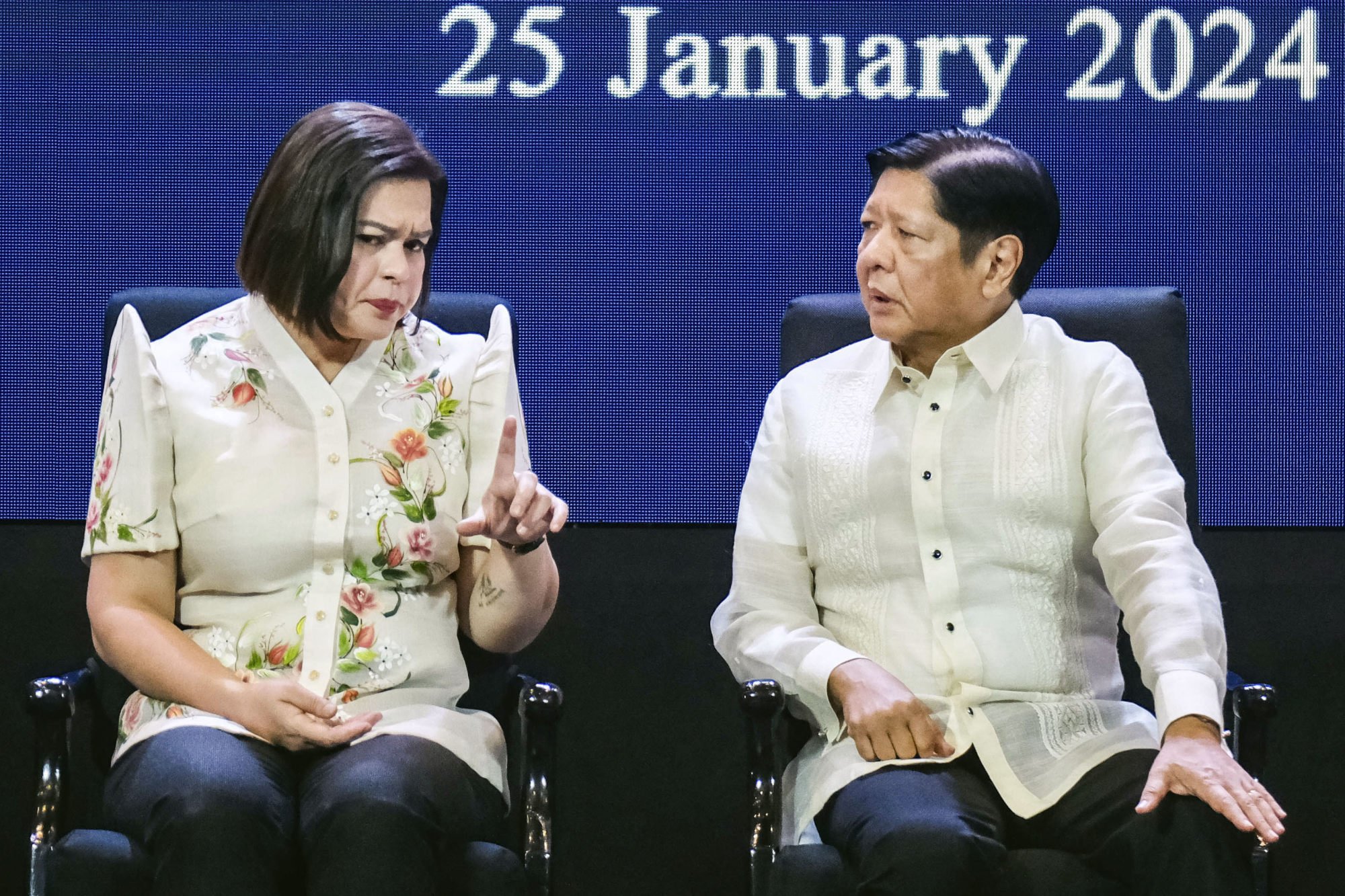

Trillanes reiterated to This Week in Asia that he believed the Duterte family had put in motion a plot to remove Marcos Jnr from power and replace him with Vice-President Sara Duterte-Carpio, the former president’s daughter.

Trillanes and political risk analyst Ronald Llamas said one of the options the Duterte family was exploring was a mass withdrawal of support by pro-Duterte policemen against Marcos Jnr to trigger a political crisis.

Llamas told This Week in Asia on Monday that a withdrawal of support for the government, followed by a massive demonstration of “people power” in the streets, was what triggered the political crisis against then-president Joseph Estrada in January 2001, which led to his bloodless ouster.

But Llamas pointed out that because of a peculiar section in the Philippine constitution, any planned ouster of Marcos Jnr would have to happen after June 30 and not before for any plotter to rule as president for a longer period.

“This is called the June 30 GMA framework,” he said, referring to the initials of former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who served as president for nine years.

Section 4 of Article VII of the constitution specifies that any successor to the president can no longer run for a fresh presidential term of six years if he has already served the unexpired term of the previous president “for more than four years”. Marcos Jnr has served as president since June 30, 2022.

After June 30 of this year, this constitutional provision will not apply, so if Marcos Jnr is removed from power, his successor could serve the rest of his term and still run for another six years.

Llamas, however, pointed out that while destabilisation may be Duterte’s agenda, “to abide by the June 30 scenario would be hard because destabilisation depends on the convergence of a ripe objective condition and the readiness of subjective forces”.

Two attempts at presidential overthrow have succeeded in Philippine history – the 1986 ousting of Marcos Jnr’s father, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos Snr, by a peaceful people power uprising and Estrada’s “resignation” in 2001.

Marcos Jnr appeared to be taking the possibility of a plot to oust him very seriously.

On May 16, he told soldiers in a military camp in Cagayan de Oro City in southern Mindanao: “We will also not allow agents within the country to destabilise our government and create division within our nation.”

He told fresh Philippine Military Academy graduates three days later to guard against “blatant attempts of destabilisation, and last-ditch [efforts] to cling to the rapidly disappearing past”, in an apparent reference to Duterte.

On May 23, he went to a remote military camp in the island province of Tawi-Tawi in Mindanao and told the 2nd Marine Brigade that “when I go around our camps, I always explain that our mission is to fight those who are trying to overthrow the government, for whatever reason”.

A senior military officer said those in the military were not inclined to oust Marcos Jnr, preferring to focus on fighting for the country’s sovereignty in the South China Sea.

He told This Week in Asia, on condition of anonymity, that many would prefer that Duterte be sent to The Hague to face charges before the ICC.