“My understanding is ‘there will be trouble’ if we insist on our own way there in the West Philippine Sea. China will go to war,” he added.

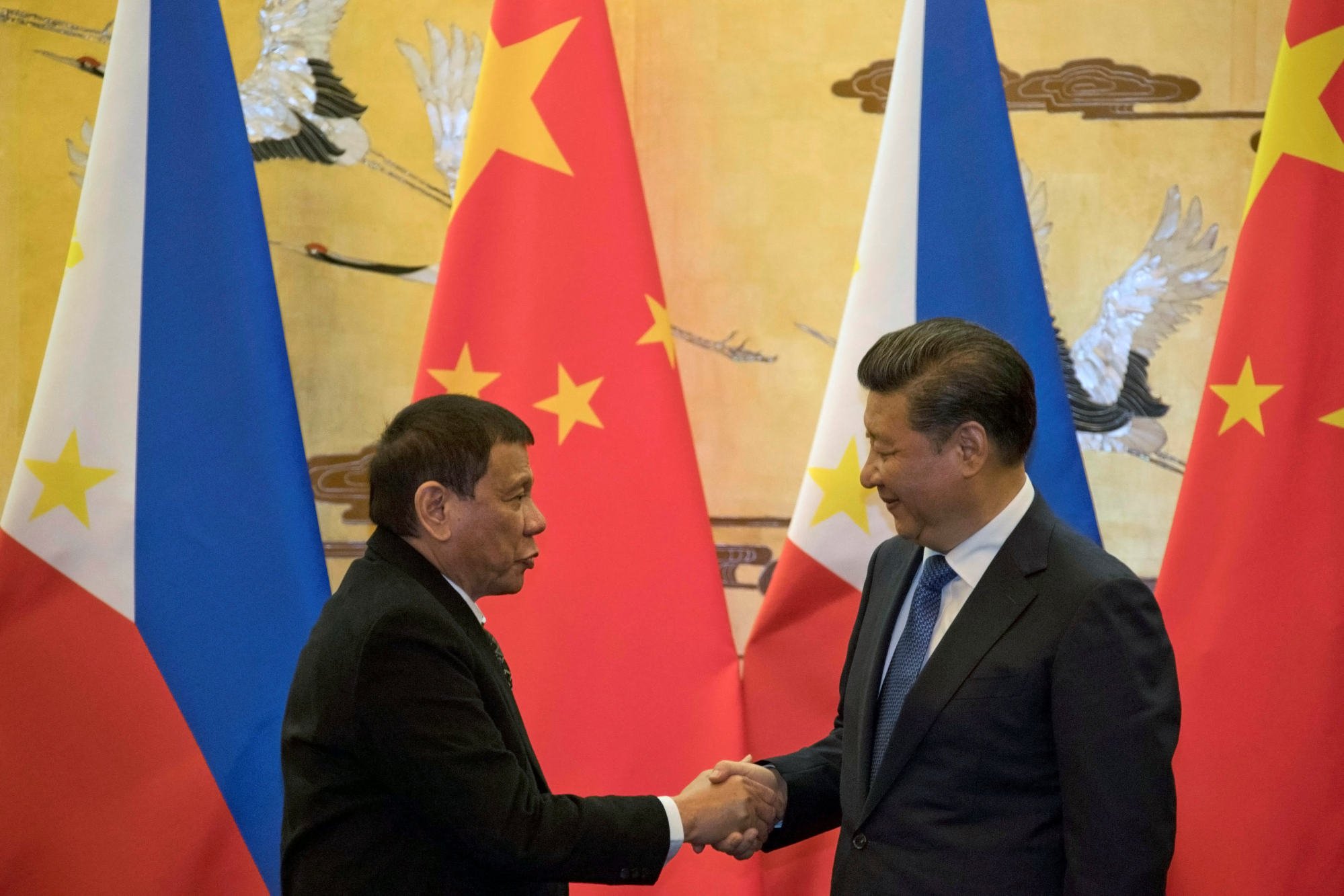

Duterte also denied that he had ever struck a “gentlemen’s deal” with Xi that would entail forfeiting his country’s territorial rights, and that the only thing they agreed on was maintaining the status quo within the disputed waters, meaning no new facilities or infrastructure.

“Aside from the fact of having a handshake with President Xi Jinping, the only thing I remember was ‘status quo’. That’s the word,” Duterte said.

Roque speculated that Beijing felt Manila’s missions to the Second Thomas Shoal to resupply the BPS Sierra Madre – a WWII era navy vessel that was purposefully grounded on the shoal to bolster the Philippines’ territorial claims – was a violation of the unwritten agreement made by Duterte.

During his six years in office, Duterte, who consistently called Xi a very close “friend”, reoriented Philippine foreign policy away from the United States towards closer ties with China.

China has competing claims in the South China Sea with the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam. In 2016, a UN arbitration court ruled in favour of the Philippines, invalidating China’s historical claims on much of the disputed region’s waters. Beijing, however, rejected the ruling and continues to insist that it has jurisdiction over everything within its nine-dash boundary claim.

Manila and Washington have an existing 1951 Mutual Defence Treaty (MDT) that calls on both countries to aid each other in times of aggression by an external power.

“United States defence commitments to Japan, and to the Philippines, are ironclad, they’re ironclad,” Biden told the media. “Any attack on Philippine aircraft vessels or armed forces in the South China Sea would invoke our mutual defence treaty.”

Calibrating alliances

“The only reason there is this perception that we are leaning more towards the US is because the past administration set aside our long-time friendship with the US,” he told This Week in Asia.

Tayao said he believed Marcos Jnr was doing the right thing, not just by leaning towards the US but by expanding the country’s foreign policy options by strengthening relations with other nations, such as Japan, as well.

Both the US and China would think long and hard before doing anything in the South China Sea that would risk bringing them into conflict, Tayao argued, noting their economic interdependence on trade.

Renato Cruz De Castro, a professor of international studies at De La Salle University in Manila, told This Week in Asia that the US would only act in defence of the Philippines if it was in its own self-interest.

“We have a treaty relationship with the US, not because we like each other, but because we are faced by a greater threat and that is China,” De Castro said.

“You have to understand the notion of alliance. The alliance [members] do not like each other. Alliances are formed because you have a greater threat and that is China. We share a common interest and of course that is to prevent China from becoming the dominant power in the region,” he added.

“Historically, if you look at the case of World War I, Britain and Germany were economically linked. The same in the Pacific War, Japan and the US were economically linked together also. But after the first shot has been fired, economic interdependence simply does not really matter,” De Castro warned, adding “Manila has to prepare for the inevitable”.