Big-money art is a barometer of the global economy and New York’s annual Asia Week – a magnet for well-heeled collectors, auction houses, museums, dealers and art groupies – is among the most prestigious events on the global art calendar.

While sales of Chinese antiquities last month held up in the face of wobbly Chinese stock markets and Beijing’s efforts to stem capital flight, the news was India’s contemporary market, which is on fire.

“A very dramatic change is the flip between China and India. That’s the big story of this season, that India has usurped China as the most exciting place,” said Henry Howard-Sneyd, Asian art chairman at Sotheby’s, a rival global auction giant.

“The economy in China is definitely putting a brake on the market. Getting large tranches of funds out is not as easy as it was.”

While the Chinese art market is far larger and more extensive than India’s, and contemporary art is worlds apart from antiquities, the Indian results are turning heads, highlighting the country’s growing wealth and confidence.

China artists, dealers pin hopes on domestic collectors as global interest wanes

China artists, dealers pin hopes on domestic collectors as global interest wanes

India’s GDP last year was 7.7 per cent compared with China’s official 5.2 per cent figure, as Beijing struggles with youth unemployment, wobbly stock markets and a property crisis.

The most expensive lot during New York’s Asia Week was Kallisté, a painting by the Indian modern artist Sayed Haider Raza that Sotheby’s sold for US$5.6 million – nearly double its estimate. And Christie’s set a record for the Indian artist Francis Newton Souza, with a US$4.9 million price tag for The Lovers, nearly five times its expected high.

“They’re coming in at the very top of the market,” said Nishad Avari, a contemporary Indian art specialist at Christie’s.

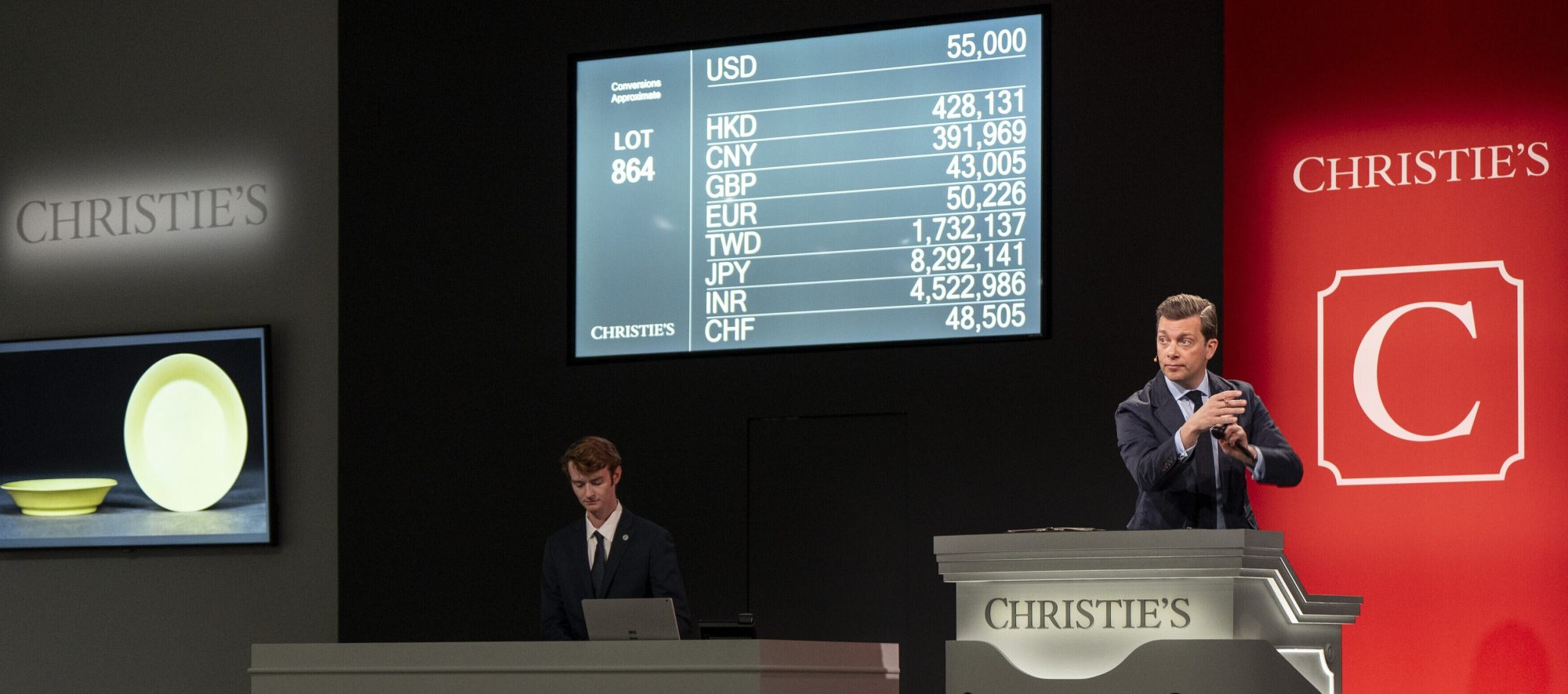

During the glitzy event, which ran from March 14 through March 22, Christie’sreported China sales of US$19.1 million, a 4 per cent increase over March 2023, while Sotheby’s reported US$10.3 million, a 46 per cent decline.

Meanwhile, on the modern and contemporary South Asian art side – mostly Indian – Christie’s saw sales of US$19.7 million, up 65 per cent over 2023 levels, while Sotheby’s nearly tripled to US$19.8 million.

In another sign of market enthusiasm for South Asian art, Christie’s sold every one of the 93 lots it offered.

“A 100 per cent success rate is indeed a rare event,” industry tracker Artprice.com noted. “Collectors are currently highly motivated.”

While Chinese antiquities held steady despite wars and global instability, the market is hardly immune from the economic winds battering the Middle Kingdom.

China’s rise in art market fosters demand for advisory services from banks

China’s rise in art market fosters demand for advisory services from banks

“If you’re worth US$50 million one day and US$40 million the next, you get grumpy,” said Eric Zetterquist, founder of New York-based Zetterquist galleries, which specialises in Chinese ceramics. “Where you or I may decide not to buy a sweater, for them that trickles up to bigger and bigger numbers.”

Supply is also a significant factor, with total auction sales dependent on when collections become available – often tied to the death of long-time collectors.

A big part of the job for auction art specialists is to build close relationships over years, even decades, so they get first crack at an estate.

Some heirs know the value of their inheritance, others do not. Vicki Paloympis, head of Christie’s Chinese art department, has found a valuable jade piece used as a toothbrush holder and a Chinese 15th-century dish doubling as a “dog bowl”, underscoring the importance of investigating every nook and cranny.

And Howard-Sneyd has come across Chinese porcelain used as lamps, umbrella stands, coin holders and doorstops. “Once it passes to next generation the sense of true value tends to dissipate fast,” he said.

Auction houses struggled during the pandemic amid suspended sales and in-person restrictions, although many regrouped by creating virtual reality renditions of their pieces for online bidding.

Major houses hold auctions in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong, but Asian buyers often flock to New York partly for the assurance that a piece is real, well vetted and backed by a history of documented ownership, or provenance. As China’s manufacturing prowess has grown exponentially, so has its ability to produce fakes – from trainers to designer bags to “priceless” art.

“There’s an element of trust if you’re spending US$600,000,” said Paloympis, a 13-year Christie’s veteran who studied Chinese in Nanjing. “Buyers look to New York for that.”

“Everyone did it,” Xiao told the local court, adding that one of his fakes was itself stolen – the thief evidently thought it was real – and replaced by a “terribly bad” fake.

University librarian in China admits he replaced famed artworks with fakes for years

University librarian in China admits he replaced famed artworks with fakes for years

Wary of counterfeits, Chinese buyers tend to be more hands-on; they take longer and are more exhaustive in their due diligence, experts say, using coloured lights and enlarged photographs to search for microscopic blemishes.

At Christie’s presale last month, prospective Chinese buyers pawed, shook and caressed the precious objects on offer – in sharp contrast with guards barking “do not touch” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art nearby.

“It doesn’t happen with other sales,” said Edward Lewine, a Christie’s vice-president, watching a potential Chinese buyer in a blue jacket spend 15 minutes poring over a white porcelain vase. “It’s so tactile, so intense.”

If a customer starts taking too many pictures, however, they’re shown the door, amid concerns they may be doing research to craft their own fakes.

Another reason well-heeled Chinese and Indians come to New York for in-person auctions is to get around patchy phone and internet lines, a problem when connections drop off in the middle of a million-dollar auction.

The Indian century is finally here

“You coming in?” Kleiweg de Zwaan asked a colleague manning a telephone line midway through bidding on a “rare huanghuali square table” after the line dropped. “If you’re going to wait, I’ll wait too.”

“You think you’re talking to someone and then they’re gone,” Paloympis noted.

Until recently, Indian artists remained in the shadow of their Chinese counterparts – few Indians, for instance, have the name recognition of artist and activist Ai Weiwei – but the roots of Indian contemporary art are older, deeper and more international, drawing on German expressionism, surrealism and cubism.

That depth has helped interest surge since 2022, amid mounting buzz and shattered auction records. “Quiet confidence has turned into bullishness,” The Art Newspaper gushed in February. “The Indian century is finally here.”

The robust Indian contemporary art scene stands in contrast to the overall market. Total gallery and auction house sales during last month’s Asia Week were US$100.8 million, down 24 per cent from a year earlier.

Experts estimated a 50-50 split between Asian and US buyers this year, with many “global” buyers of indeterminate citizenship owning flats in London, New York or Hong Kong, acquiring expensive pieces as a store of wealth, a nouveau riche calling card or a treasure easily moved without the paperwork and scrutiny of China’s cultural heritage bureau.

Art retrieved from tombs – generally Tang dynasty (618–907AD) and older – tend to attract more buyers among non-Asians, given Chinese superstition around the deceased, though experts say is starting to change as prices rise.

Shanghai’s Art021 art fair to launch Hong Kong version in summer 2024

Shanghai’s Art021 art fair to launch Hong Kong version in summer 2024

Foreign collectors have also traditionally been less concerned if something has a few nicks, while Chinese tend to hold out – and be willing to pay – for picture-perfect pieces.

“Chinese are much more about condition and perfection of form,” Zetterquist said.

China’s recent art world sway over India has been fuelled by a few factors. Among antiquities, this reflects in part the fragility of Indian materials, including sandstone and textiles, relative to Chinese commonly used jade, porcelain and stone. Modern Chinese art has also seen more money thrown at it, and more exposure, though Indian experts hope to see the balance change.

“If you go to any museum, you will see a much broader and deeper Chinese works of art holding than any modern art from South Asia,” said Avari of Christie’s, noting that New York’s Museum of Modern Art only started displaying Indian art five years ago.

“Growing wealth in India plays a big role in growing awareness of cultural currency,” he noted.

But Chinese art has been collected for centuries outside the country – including Japan’s 1,000-year history of acquiring Chinese porcelain for its tea ceremony – providing an ample supply, greater transparency and less bureaucracy.

“You don’t need to go there, don’t need to rock the boat,” said Paloympis.

After handing off the dais to another auctioneer, Kleiweg de Zwaan reflected on the showcase week, growing importance of Asia on the global art stage and art of creating excitement that may see bidders pay more than they expected.

The art world had become less formal and stodgy since he attended auctioneer school in 2008, he reckoned, with many of those bidding tens of thousands of US dollars dressed down in baseball caps, hoodies and heavy black boots these days. But the basic auctioneer skills remain: an ability to entertain, keep up the energy and remain in control of the room.

“It’s sort of like being a DJ – with paddles,” the Netherlands native said. “I love Asian Art weeks, especially the Chinese works of art, the depth of bidding, the amount of people that come to be in the room.

“It’s a testament to how deep that pool of collectors is, not only in Asia but around the world.”