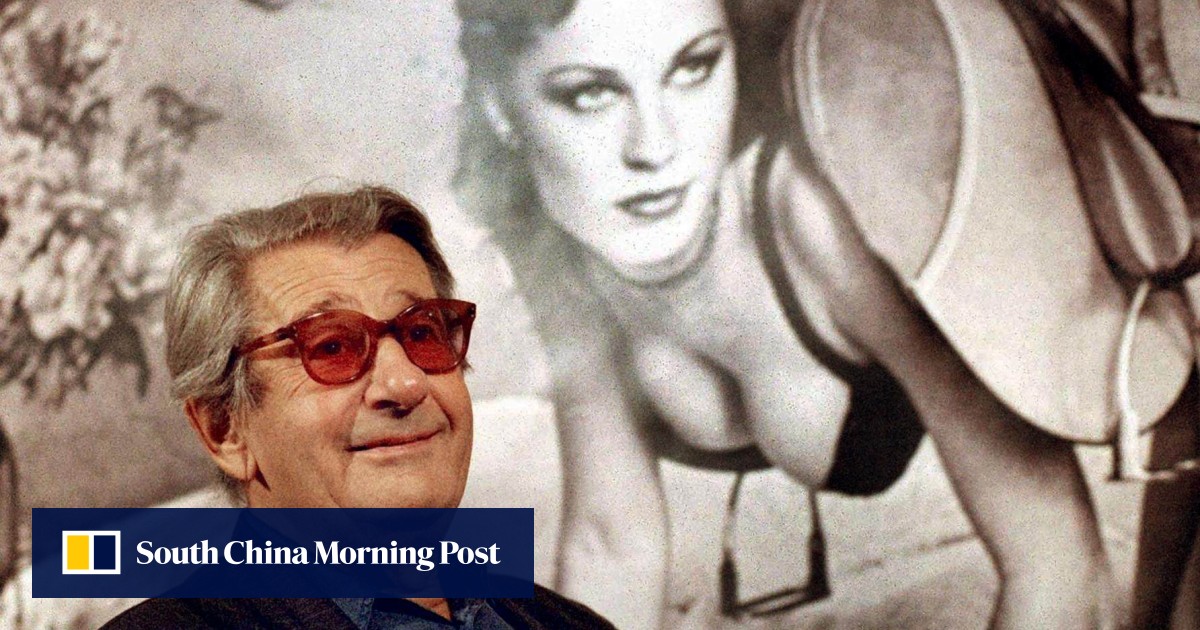

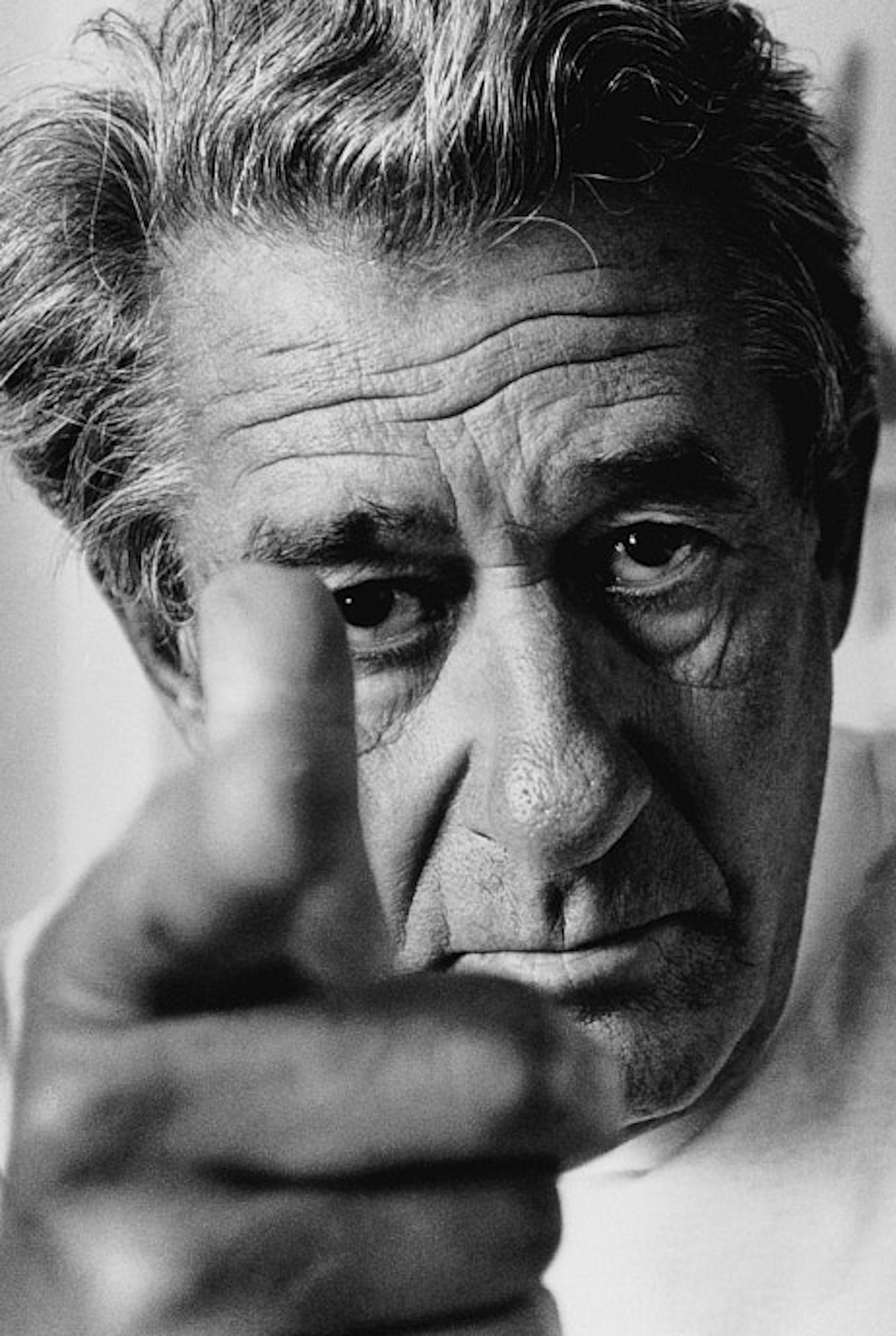

His seductive and subversive images made German-Australian photographer Helmut Newton one of the most celebrated image-makers of the 20th century.

Now, a large-scale exhibition, “Helmut Newton: Fact & Fiction”, opening on November 18 at the Marta Ortega Pérez Foundation in A Coruña, Spain, will show some of his most famous images, alongside others that provide a well-rounded sense of the photographer’s range, including Polaroids he took on set during photoshoots, and atmospheric shots of places he visited.

“Helmut was by nature a re-constructor of things he had seen,” says Philippe Garner, vice-president of the Helmut Newton Foundation, who co-curated the exhibition alongside Matthias Harder, the foundation’s director, and Tim Jefferies, director of Hamiltons Gallery in London.

“There’s a real documentary dimension to his work. He’s recording the way a certain kind of woman might live, but he makes his pictures by building them artificially. They are a fiction that in a sense represents a fact.”

Born into a prosperous Jewish family in Berlin, Germany, in 1920, Newton was fascinated by photography from a young age.

“He would later say that his interest in those years was swimming, girls and photography – he put the girls and the photography together, and took up fashion photography,” Garner laughs.

Young naked women are their canvas – Hong Kong artists’ erotic nude art

Young naked women are their canvas – Hong Kong artists’ erotic nude art

After growing Nazi persecution led Newton to flee Germany in 1938, he landed in Singapore, where he worked briefly – and rather unsuccessfully – as a photojournalist for The Straits Times.

“It wasn’t the moment that appealed to him, it was the distillation of things observed,” Garner says.

The outbreak of World War II led to Newton’s internment in Singapore before he was sent to Australia, where he served in the army and eventually took citizenship in 1946.

Keen to make a living from photography, he set up his own studio in Melbourne after the war, where he met his future wife, the Australian actress June Brunell.

At the end of the 1950s, the couple returned to Europe and settled in Paris, the epicentre of high fashion, where Newton entered his formative era and established his name through the edgy, provocative shoots he produced for various fashion publications.

“They were tough,” Garner says of the photographer’s signature style, which could provoke unease and offend as easily as it could seduce.

“It was his choice of women, choice of settings and his mastery of instruction in posing the models. He could get so much out of a gesture, out of a little frown. His pictures were clearly built with such deliberation and effectiveness that set him above most others.”

Famously economical with film – Newton could fit an entire shoot onto a single roll – these erotically charged tableaus were meticulously mapped out in his mind.

Yet, like all great artists, he also left something open to the intervention of chance.

“There was a dynamic where you weren’t quite sure if it was predetermined or spontaneous,” Garner says.

“Keeping that energy alive in the picture meant it didn’t look stiff. That was the balancing act of pulling off a Helmut picture.”

As a self-described “image-hungry” teenager in the 1960s, Garner avidly cut out photographs from magazines and it wasn’t long before he started noticing Newton’s name.

“I liked those pictures that were soaked in the flavour of old Europe, where he was drawing on memories of his childhood,” he says.

“His parents used to take him travelling. They would stay in fancy hotels and spas. Quite apart from the fashion or erotic elements, I really responded to those pictures that had this layer of cultural history that was very much central to his oeuvre.”

The ambivalence, the ambiguity – that is what makes Helmut’s pictures last

Newton held his first solo exhibition in 1975, where Garner, through his career as an auction specialist for photography, met him for the first time; he remained a close friend and associate thereafter.

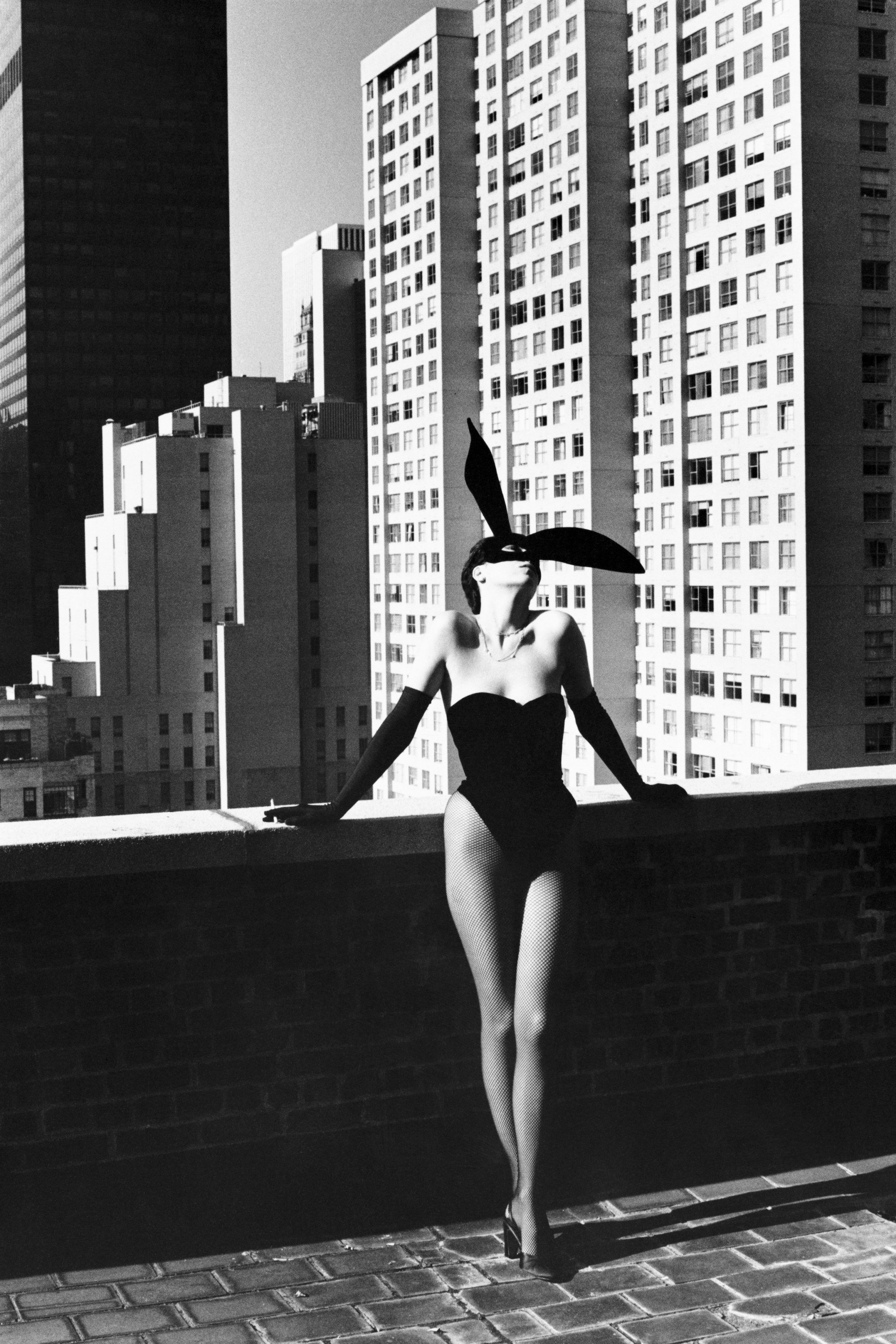

The year 1975 was seminal in other ways: some of Newton’s most iconic photographs date from this year, including Elsa Peretti as a Bunny and Rue Aubriot, which hang side by side in the coming exhibition.

A landmark in the canon of fashion photography, Rue Aubriot not only cemented Newton’s reputation but articulated the transgressive sensuality of Paris’ most talked-about designer, Yves Saint Laurent.

Artists bare intimate personal memories on Hong Kong’s most public stage

Artists bare intimate personal memories on Hong Kong’s most public stage

Fabulously in tune, the couturier and the photographer undercut the staidness and stuffiness of high fashion, wholeheartedly embracing the sexual revolution of the 1970s.

In Saint Laurent’s designs and through Newton’s lens, a woman understood the concept of the body as a weapon and how to control and manipulate her power.

“I’ve playfully debated who invented the Saint Laurent look,” Garner says. “Was it Saint Laurent or Helmut? And who created the sublime garments that matched Helmut’s requirements? It was a great working relationship.”

Atmospheric shots of places Newton visited also form significant portions of the display. After a surfeit of fashion and glamour, his lesser-known landscapes afforded him much-needed breathing space, which ultimately helped sustain his career for over six decades.

There were moments when the photographer thought he had run out of steam. A particular low point came in 1981. A passing journey through a small seaside town reignited the spark, Garner says.

“He tells the story of a train ride to Italy, where he travels through Bordighera. He found it delightful and thought it would be a great setting for some pictures.”

What followed was a series for Italian Vogue called “Bordighera Details”, with dramatic close-ups of mouths and eyes, one of which is included in the exhibition.

In an unprecedented move, all the images in “Helmut Newton: Fact & Fiction” are “lifetime prints” – ones produced during Newton’s lifetime and previously validated by the photographer.

It serves as a nice reminder about photographs as objects in their own right, and reflects the ultimate aim of The Helmut Newton Foundation to keep the works of Helmut and June Newton (who worked as a photographer under the name Alice Springs) alive.

Although Newton did not formally establish his foundation until 2003, a year before his death, he had kept meticulous archives since 1971 – spurred by a heart attack that year to consider his posterity and legacy.

Garner notes that interest in the Newtons only continues to grow, as the foundation attracts increasing numbers of visitors.

“Our ongoing dialogue is to see how we can open up the programme in different and unexpected ways,” he says, with the objective being to exhibit other visual artists’ work alongside the Newtons’. “We are very much open for possibilities.”

Newton never returned to live in Berlin, but when it came to choosing the site to house his photographs and archive, there was no doubt that it would be there.

In a poignant gesture, the building he chose – formerly a recreation club for Prussian military officers – stands right across the street from the station where he boarded the train to flee Germany in 1938.

‘Tragedy, death, ecstasy’: huge show of Mark Rothko’s paintings in Paris

‘Tragedy, death, ecstasy’: huge show of Mark Rothko’s paintings in Paris

It marked a symbolic closing of the circle after that traumatic rupture in his adolescence – a period of his life that Newton rarely mentioned, but which would forever shape his life and his work.

“The ambivalence, the ambiguity – that is what makes Helmut’s pictures last,” Garner says. “There are layers, and they are often unfathomable layers that intrigue, engage and sometimes can be disconcerting or destabilising, but that’s the Helmut mix.”

“Helmut Newton: Fact & Fiction” will be on show at the Marta Ortega Pérez Foundation from November 18 until May 1, 2024.