All 10 are of mainland Chinese origin, from the eastern province of Fujian, but hold various foreign passports. They are alleged to have ties with organised crime.

Here are the key things you need to know about what prosecutors say is “one of the most serious, if not the worst, money-laundering case in Singapore”.

Suspects and their seized assets

Of the 10 suspects, three are current Chinese nationals: a 44-year-old man named Zhang Ruijin, a 43-year-old woman named Lin Baoying and a 31-year-old man named Wang Baosen.

The remaining seven hold different primary passports, but all have their origins in Fujian. They were also found with Chinese passports.

Su Haijin, 40, and Wang Dehai, 34, hold Cyprian passports; Su Baolin, 41, Chen Qingyuan, 33, and Su Wenqiang, 31, have Cambodian passports; Vang Shuiming, 42, has a Turkish passport; and Su Jianfeng, 35, has a passport from the Pacific island of Vanuatu.

Singapore’s US$1.3 billion probe exposes Chinese criminals’ paid-for passports

Singapore’s US$1.3 billion probe exposes Chinese criminals’ paid-for passports

Local and international media have reported that Singapore’s largest lender, DBS Bank, as well as the private banking arm of OCBC Bank, were among the creditors to investment companies linked to the 10 suspects in the case.

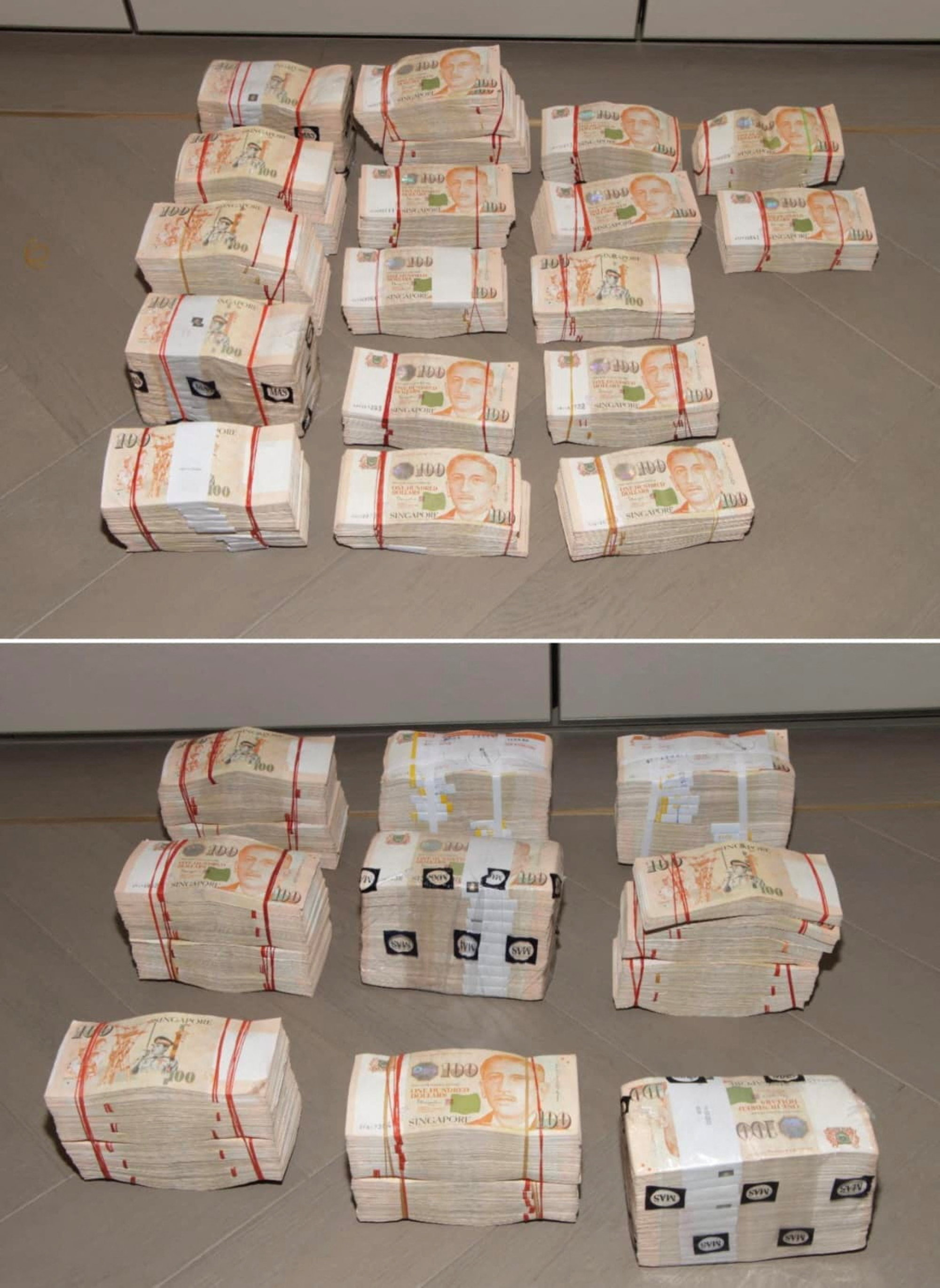

Prosecutors have so far seized S$1.8 billion (US$1.3 billion) in cash and assets from the 10 individuals, including at least 105 properties, 50 vehicles, S$123 million in cash, 250 luxury bags and watches, and 270 pieces of jewellery.

A company partly owned by Su Haijin paid more than S$73 million for two buildings in London’s Oxford Street and 11 Princes Street, according to the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project investigative reporting platform.

At least four of the 10 accused are also members of the exclusive Sentosa Golf Club, which costs around S$950,000 for foreigners to join, according to a report by Singapore broadsheet Straits Times.

The accused have hired established Singaporean law firms to represent them in the case, such as Lee & Lee, CNPLaw and Drew & Napier, among others.

How has it affected Singapore’s reputation?

While there have been suggestions that Singapore’s ultra-clean reputation may have taken a hit from the case, observers have also emphasised that it was investigated by authorities of their own volition.

What will determine the republic’s overall standing as a financial hub is the “resolve in enforcement”, said Singapore-based business professor Lawrence Loh.

The city state’s total assets under management stood at S$5.4 trillion in 2021, compared to S$2.7 trillion in 2016, according to the latest available data. That figure is likely to be considerably higher now as hot money inflows have continued unabated in the years since.

“On the whole, investors will be watching how Singapore makes resolutions for a better and safer financial locality – it may well turn out to be in the country’s favour if the case is managed well,” said Loh, director of the National University of Singapore’s Centre for Governance and Sustainability.

“It will take more than this money laundering happening for Singapore’s reputation as ‘Switzerland of the East’ to really take a serious hit,” he said, referring to the moniker applied to the city state by pundits given its now-entrenched status as one of Asia’s go-to wealth management hubs.

It will take more than this money laundering happening for Singapore’s reputation as ‘Switzerland of the East’ to really take a serious hit

Even if Singapore were to put all the necessary regulatory frameworks in place, it would not completely eliminate all possibility of money laundering, Loh said, stressing the need for tight enforcement of big-ticket purchases such as club memberships, real estates and luxury cars, which may require a whole-system approach.

“These will be good checkpoints to nip any problems in the bud. But the challenge is the delicate balance between overregulation and being business-friendly,” he said.

What do Singaporeans think?

The case has rekindled an already intense debate among locals about the island nation’s yawning income and wealth gap. On social media, many juxtaposed the upper-class lifestyles of the 10 suspects – parsing images of the seized Bentleys and homes – with their own struggles amid the rising cost of living.

“While they are enjoying their lavish lifestyles in Singapore for the past six years pumping dirty money into our economy, ordinary Singaporeans pay the price of distorted inflation unknowingly,” read a comment on Facebook in response to a news article about the investigation.

Singapore readies anti-money-laundering system roll out to prevent a 1MDB repeat

Singapore readies anti-money-laundering system roll out to prevent a 1MDB repeat

Among the intelligentsia, the money-laundering case has been examined as a symptom of what they call unbridled globalisation and openness to foreign talent and wealth that have come at the expense of locals’ interests.

This trend has resulted in Singapore being seen as a way station by some of its residents, while others see it as a home or a bit of both, according to Sudhir Thomas Vadaketh, editor of weekly magazine Jom.

“There’s an inherent existential tension between the two that expresses itself in different ways, and requires perpetual management from politicians and bureaucrats,” Sudhir was quoted as saying in a recent Financial Times report about the case. “The money-laundering case, for many people, reminds us that we may be leaning too much towards ‘global city’.”

What has the government said?

The most extensive official comments on the case have come from the law and home affairs minister, K. Shanmugam, in an interview with local Chinese-language daily Lianhe Zaobao.

The veteran minister labelled speculation about Beijing giving the green light to the investigation as “absurd”, stressing that Singapore does not “yield to that sort of pressure from any country”.

He said that investigations started because authorities “had reason to believe that these people had committed offences in Singapore”, and not “at the request of some foreign country or party or because of external pressure”.

When he was asked about whether the case would dent the country’s reputation as a global financial hub, and could see it become a hotspot for money-laundering activities, he warned against making such characterisations and said that similar activities occurred in other financial centres like London and Hong Kong.

“It’s like a major highway. Some criminals will also try and use the highway, and they will try different methods, quite sophisticated, they’ll mix some illegal transactions with many legitimate ones, to make it difficult for you to find, so that it’s not always clear cut,” he said.

‘People are having doubts’: is Hong Kong losing its edge to Singapore as legal hub?

‘People are having doubts’: is Hong Kong losing its edge to Singapore as legal hub?

The bottom line was that by taking action as soon as the authorities had the facts, Singapore sent “a clear signal that we are a no-nonsense place”, Shanmugam said. “We’ll act against people who abuse our system.”

Heng Swee Keat, one of the republic’s two deputy prime ministers, echoed this view at a Forbes conference in the city state this week, saying that Singapore had been “vigilant” about illicit activities such as money laundering, in response to a question about the case.

“Financial centres all over the world will face this challenge, because so much money is moving around,” he said.

“In fact, if at all, it is a call for all of us to be very vigilant because every transaction will have a financial element, and the fact that we are vigilant is a plus and we have every intention to keep it that way.”