Philippine military spokesman Medel Aguilar shot back the next day, accusing China of performing dangerous manoeuvres. “They are the ones committing all the violations,” Aguilar said on state-run broadcaster PTV.

Philippines says it’s not provoking conflict, accuses China of ‘dangerous’ moves

Philippines says it’s not provoking conflict, accuses China of ‘dangerous’ moves

The incident was highlighted extensively on social media in both countries. Neither Hanoi nor Beijing, however, confirmed what happened – the official reticence reflecting both sides’ desire to avoid further escalation, according to analysts.

None of these grey-zone tactics constitute an act of war, but analysts said they are part of China’s carefully calculated strategy to strengthen its territorial claims over the waters without escalating the conflict.

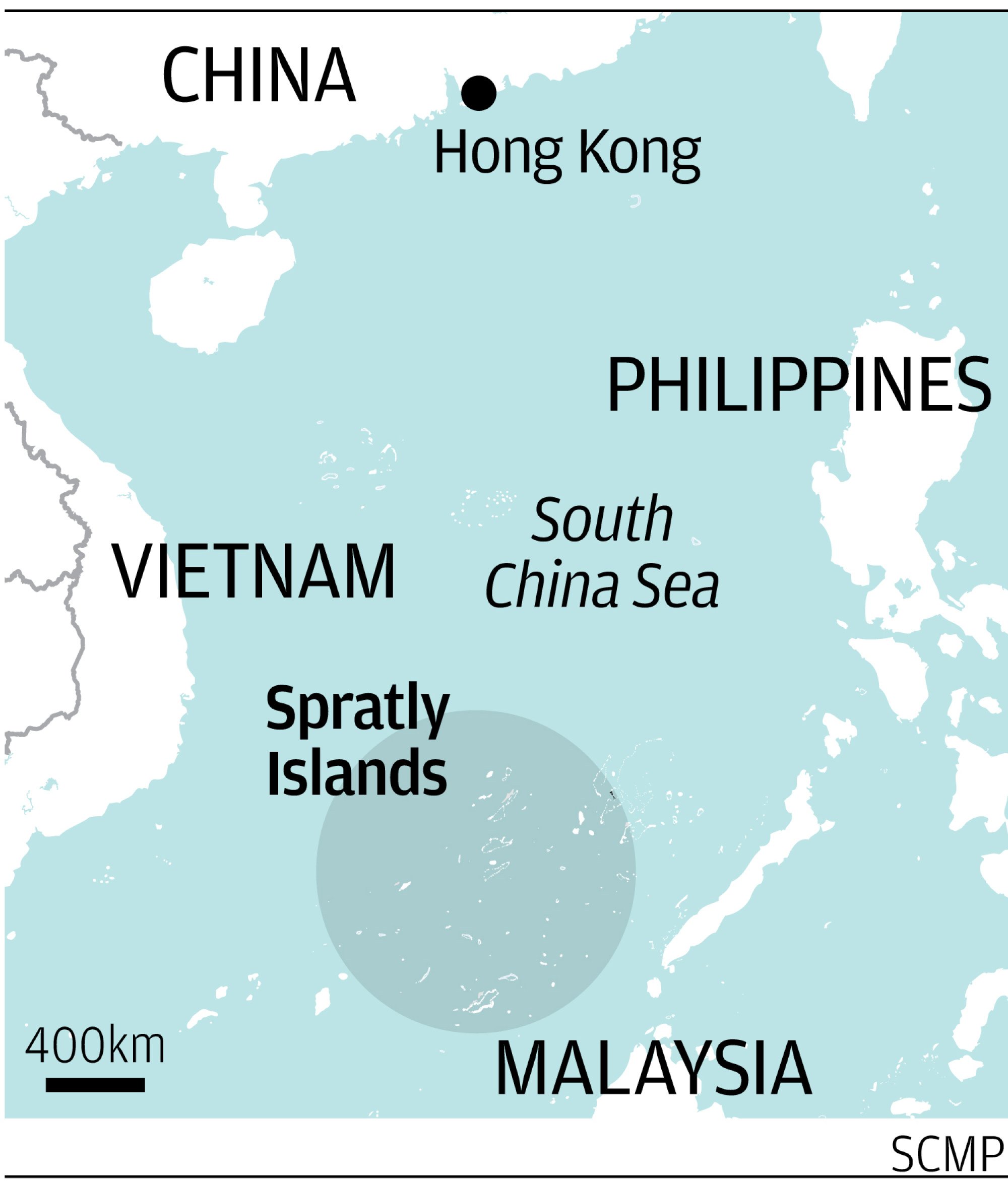

While Beijing has been undertaking similar actions in the South China Sea for years, observers have noted a significant increase in the frequency and intensity of grey-zone activities in 2023. Marcos Jnr’s increasingly confrontational posture and heightened nationalist sentiment in China mean neither side is likely to back down and escalation may be inevitable, according to analysts.

Grey-zone gains

Although Chinese officials say negotiations are the most feasible way to deal with the South China Sea issue, Beijing has continued to engage in frequent grey-zone provocations as a means of strengthening its position.

The grey zone approach has delivered gains for China, advancing its position in the disputed sea without triggering conflict thus far

“The grey zone approach has delivered gains for China, advancing its position in the disputed sea without triggering conflict thus far. It allowed Beijing to undermine the position of other disputants in contested spaces while maintaining deniability,” Lucio Blanco Pitlo III, a research fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation, told This Week in Asia.

Collin Koh, a senior fellow specialising in defence and strategic studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said this year’s incidents concerning the waters were China’s way of embarking on “horizontal escalation”, which has happened more regularly and with greater intensity.

“It’s so far avoided vertical escalation, which would entail actions that it has hitherto avoided such as boarding and inspection of foreign vessels, as well as the use of kinetic force,” Koh said.

Assertive counterstrategy

Nonetheless, analysts said while China’s actions were carefully calibrated to be as disruptive as possible and stopped short of acts of war, avoiding conflict might not be China’s ultimate goal.

Koh said it is plausible that China’s grey zone tactics “are designed to bait the other party into escalation, which would thus free Chinese forces to respond in kind – and the use of force would then be legitimised as a form of self-defence or response in kind to what the other party does”.

It is difficult to know if the frequency of grey zone actions has increased in the past year as several incidents involving South China Sea claimants have been unpublicised, analysts said. Most of the recent reported incidents were based on information released by the Philippine government and military.

“When Duterte was president, his tendency to keep incidents in the South China Sea under wraps quickly facilitated China’s grey zone actions with minimal consequences,” Koh said.

Other Asean countries with interest in the disputed waters, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, have preferred to keep the issue “low profile” due to their significant trade with China.

Opinion | Manila’s South China Sea ‘name and shame’ policy has Beijing on the back foot

Opinion | Manila’s South China Sea ‘name and shame’ policy has Beijing on the back foot

John Bradford, executive director of the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies, argued the dent in China’s image has been significant. “By blatantly disregarding international law and showing its readiness to push around its neighbours, China has shown itself as untrustworthy and has undermined its opportunities to resolve issues without force.”

Is further escalation inevitable?

While assertive transparency may be an effective counterstrategy, some analysts are wary that it could still lead to escalation rather than deterrence.

Pitlo said China is “upping the pressure” against the Philippines, possibly to induce its neighbour to refrain from publicising and “internationalising” the bilateral dispute and instead return to dialogues, such as through the Philippines-China Bilateral Consultative Mechanism, and regional frameworks like the proposed Asean-China Code of Conduct (COC).

It is dangerously likely that one of the grey-zone skirmishes could result in a collision or deaths

China’s leaders are unlikely to back down on their South China Sea claims, particularly as the dispute provides a useful diversion amid the hard questions they are facing about the country’s current economic slump, Koh said.

“When the Communist Party of China’s domestic political legitimacy is at stake, given the [potential] breakdown of the social compact that’s based on the party and state delivering economic prosperity, it becomes imperative to assert its role as guardian of maritime sovereignty and rights against external foes – primarily the US and “vassals” such as the Philippines,” Koh said.

Manila risks Beijing’s wrath with ‘non-starter’ South China Sea mini pact plan

Manila risks Beijing’s wrath with ‘non-starter’ South China Sea mini pact plan

As such, the South China Sea dispute could intensify to alarming levels next year, according to analysts.

“It is dangerously likely that one of the grey-zone skirmishes could result in a collision or deaths. Given the attention focused on these issues it may be difficult to de-escalate from such a crisis,” Bradford said.

Pitlo agreed, saying that “the risk of accidents is high, especially in the absence of functional bilateral crisis management tools”. He predicted that the Second Thomas Shoal and the Scarborough Shoal would remain key flashpoints over the next year.

Tensions have also been exacerbated by the increasing US presence in the South China Sea, Koh said.

The American actions may be perceived by Beijing as a sign that Washington intends to play a more active role in the waters including taking part in joint escorts with the Philippines for missions to the Second Thomas Shoal or at least positioning US military assets to provide cover to the Philippine convoy, Koh said.

“We see the South China Sea scenarios for next year are fraught with numerous sources of uncertainty and even if the risk of a premeditated clash is low, we can’t discount the potential of inadvertent armed confrontation.”