Often living far from their families, many became respected figures in their hometowns as they sent money back to their parents and other family members.

The phrase “self-combed women” derives from the Chinese tradition of women transitioning from an unwed woman’s braided hairstyle to a combed-up bun once they were married. The zishunu “combed up” their hair on their own without a husband.

“We know that the custom was well established by the early 1800s and became more common by the early 1900s,” says Kenneth Pomeranz, a professor of Chinese history at the University of Chicago. “Around 1930, perhaps 3 per cent of the women in Shunde [a district in Guangdong] were zishunu.”

How a sexually assaulted domestic worker fought for justice across borders

How a sexually assaulted domestic worker fought for justice across borders

This phenomenon arose because many of the villages in the Pearl River Delta region had a unique feature: there were boarding houses for boys and girls that would accommodate teenagers who were living away from home.

“These houses helped to legitimise non-marital living arrangements and helped to form bonds that sometimes then carried over into the rejection of marriage,” Pomeranz says.

Originally most of the zishunu worked in the booming silk industry. By the 1930s, with silk production on the decline, many of the zishunu moved to big cities, such as Hong Kong, Singapore and others in Southeast Asia, and worked in factories or as domestic helpers for Chinese families.

In the exhibition, Hong Kong artist Kurt Tong’s photography project tells a very intimate life story of a zishunu – Mak, a petite woman who worked as help for his family for almost 40 years – and how such an unassuming figure, who died in 2018, had a great impact on so many lives through her “self-combed” life.

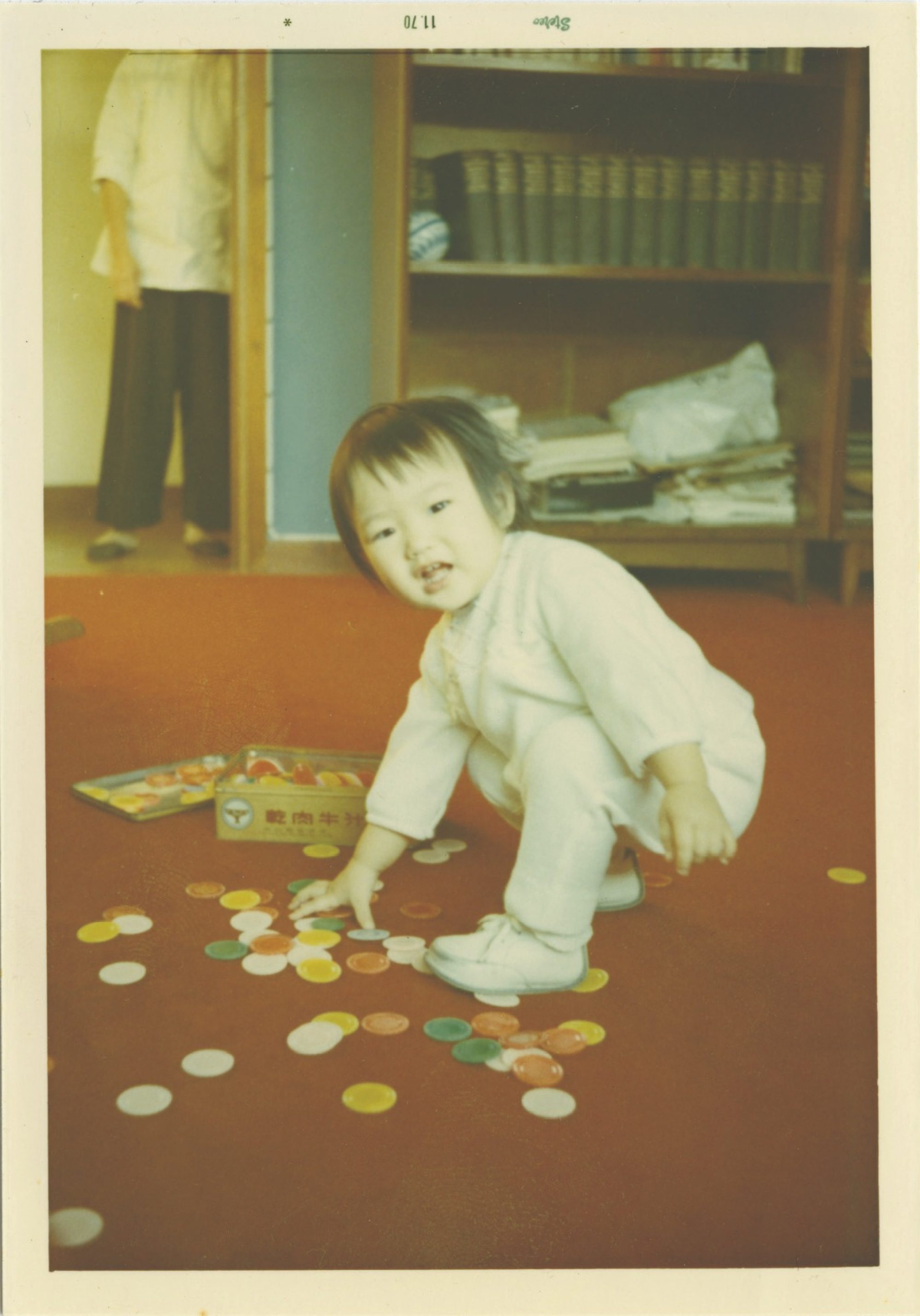

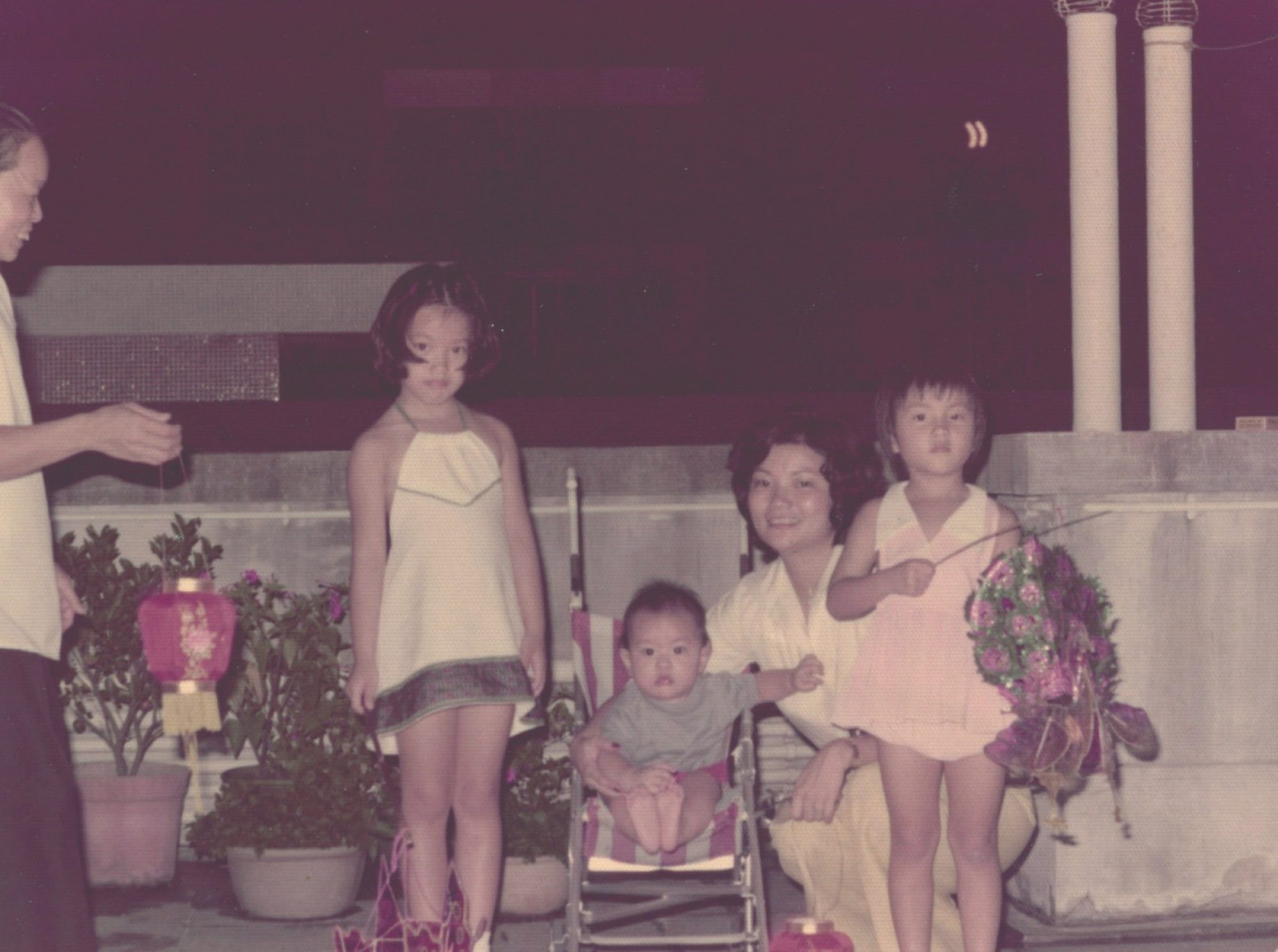

Mak was integral in raising Tong and his siblings. In the family photos that are exhibited, she is always distinctly recognisable with her white top and black trousers.

In the earlier photos, she appears only at the very edge of the frame and it seems more like an accident that she was captured.

In one photo, she is briskly passing by a dining table full of children, a birthday party for one of Tong’s siblings. In another photo, which captures a toddler standing on a rock, Mak appears on the edge again, reaching out for the toddler to ensure that he doesn’t fall.

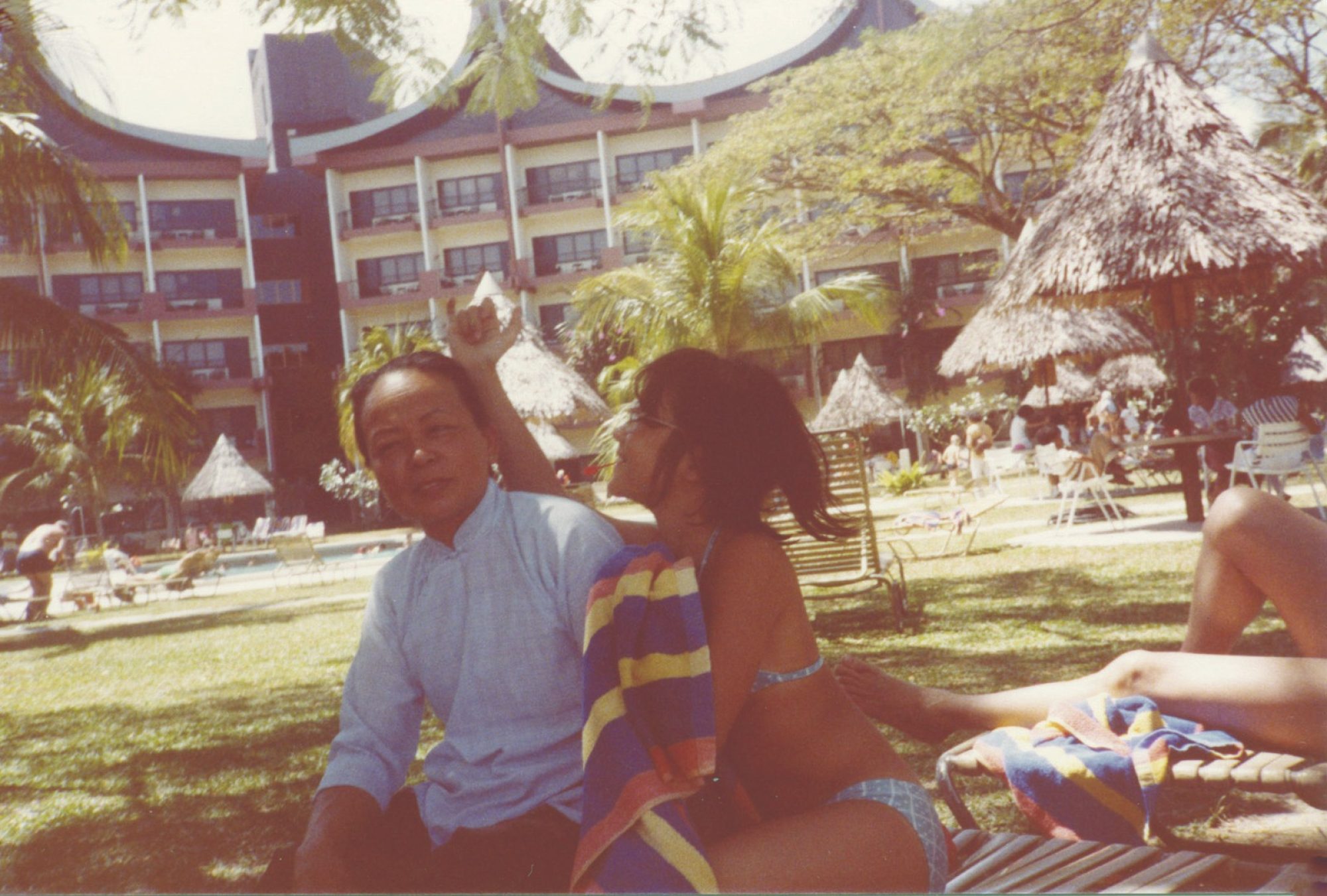

But as Tong and his siblings get older, Mak is spotted in the centre of the photos along with the family members, celebrating their birthdays together and attending university graduation ceremonies in the United Kingdom.

Mak’s life was much more than tending to Tong’s family, however. In her hometown, she became a respected figure who had achieved financial independence and provided for her family.

She kept her family alive in the late 1950s during the great famine in China. She lent generous sums of money to her nephews, which she refused to be repaid for. One of the nephews started a coat hanger factory with the money and became a millionaire operating multiple factories.

Another part of the exhibition is a photo-based research project and art installation by Chen Jialu, an artist based in Guangzhou, in Guangdong province, who documented the lives of zishunu in Southeast Asia.

Her work shows how the zishunu formed communities of sisterhood and created their own version of families with each other. Groups of zishunu often built houses together with the money they earned, where they lived together and made sure everyone was cared for. Younger zishunu would care for older ones and provide a support system usually given in a family context.

Sun says she hopes the exhibition will bring more attention to women who might have been forgotten and neglected, especially in Hong Kong.

“In Singapore, there is a permanent exhibition about these women and there are children’s books about it,” she says.

The roles the zishunu played for many families is especially pertinent to Hong Kong, a city that still benefits greatly from contemporary zishunu: foreign domestic helpers from the Philippines and Indonesia. In 2022, there were over 338,000 such helpers in the city.

Tong says that even people who didn’t have a zishunu in their lives can relate to the exhibition, as it is a poignant reminder and celebration of all of the carers that were present as we grew up.

“When I had a show a few years ago abroad, a lot of people from all over the world sent me emails and spoke to me afterwards that they had the same experience with their caregivers. I think that happens in a lot of cultures. We have women, beyond our mothers, who take on the role of caregivers,” he says.

“We are celebrating the role these women have taken. That speaks to a lot of other people beyond this region as well.”

“What even is tradition?” Chen asks. “A lot of my friends who are thinking about marriage and what it is to be a woman were really surprised to find out there’s such a marriage custom [for women not to get married] in Guangdong.

“Many people think marriage is a tradition we need to follow, but staying unmarried is also a tradition as well, as can be seen in the lives of zishunu.

“We can get a sense of inspiration or encouragement as we think about the lives most of us have forgotten in our modern life and reflect on what we can do now.”

“Daughters of Canton Delta”, The University of Chicago Francis and Rose Yuen Campus, 168 Victoria Road, Mount Davis. Jan 12-Mar 31, Tue-Sun, 10am-5.15pm, excluding public holidays