Undisputed

by Donovan Bailey

Sprinters are famously self-assured athletes. When one-hundredth of a second separates the greats from the also-rans, confidence is critical.

Donovan Bailey is a sprinter, through and through. From his idyllic childhood in Jamaica through his Oakville, Ont., teen years, and onto the globe-spanning racing career, Bailey’s autobiography reveals a man whose confidence is matched only by his ability to win the most important races in the world.

Bailey establishes his concerns in the prologue. Race and racism, self-worth, unease with many coaches, colleagues and decision makers in Canadian athletics, these are the themes that propel Bailey’s narrative.

His early years in Manchester, Jamaica are sweetly described. At the age of 11, the unabashed momma’s boy makes the permanent move to live with his dad in Canada. George Bailey has already established the Canadian Caribbean Association of Halton, Ont. Its gatherings strengthen the business and personal networks of Caribbean expats. The Baileys of Oakville have their financial house in order.

Bailey is preceded in Canada by one of his three older brothers. At 14, O’Neil Bailey is a high school sports superstar. His success eases Donovan’s entrée into athletics. Bailey frankly idolizes older, confident black men. Muhammad Ali is his lodestar.

He adores basketball, plays as much as he can, but despite a terrific vertical jump, Bailey’s sport is obviously track. The running wins come quickly. Regional youth records that O’Neil once held are ceded to younger brother Donovan.

American Colleges come calling when Bailey is 17. His father forbids him from taking a scholarship, until he has time to mature. Bailey isn’t happy about it, but rebellion is not an option. Donovan stays home to attend nearby Sheridan College. He plays plenty of hoops, and quits school after one year, perhaps proving that his dad was right about the maturation work to be done.

Bailey is precocious regarding money. He works a boiler room sales job and buys his first home at 19. A Porsche growls in the driveway.

Bailey describes a remarkable twist of fate: on a whim, he goes to watch friends at a regional meet. He shows up in office clothes. The cheering crowd kindles an urge to race again, and so, after a three year hiatus from track, he borrows spikes and running kit from a stranger, races the 100m and wins, easily.

Better late than never, he joins a track club and begins to take racing seriously. There is no arguing with his times and he quickly lands a spot on the national team.

Humbling in Havana

There is a rare career stumble at the Havana Pan Am games in 1991. Bailey is unprepared for the spectacle and he loses his concentration and blows his 100m race. He realizes that he has given the national team good reason to second guess their new guy. The next year brings more harsh life lessons.

“… I started to collect injuries like they were trading cards. There were bone spurs, hamstring issues and then, most significantly, a torn left quadricep. For the most part, I pushed through the pain. As the competition became tougher, my confidence was becoming a liability. I was treating my body like I was an immature high schooler—I thought I was invincible and could beat all those other guys even though I wasn’t in peak shape.”

His injuries cause Canadian track officials to leave Bailey off the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Team. Thirty years later, he’s still harbouring resentment at ‘the bureaucrats’ who held him back.

He tries out for bobsleigh in Calgary. The brakeman, as the fastest athlete, is last to hop aboard the sled. The training regimen does wonders for Bailey. It’s the first time in his life that he is following a full sunup-to-sundown fitness routine. He stays for nearly six months, despite figuring out quickly that bobsleigh is not his destiny.

After learning that he will not be selected for individual events at the 1993 world championships, Bailey throws a tantrum and a TV set across a room. It’s a watershed outburst. He begins to listen to his fellow sprinter Glenroy Gilbert’s coach, Dan Pfaff, who tells Bailey to get serious in his training. Bailey joins Pfaff at Louisiana State University, and at 26 years old he discovers weights, nutrition, rest. Twelve weeks later, Bailey has some pro wins under his belt.

As his races accumulate, so do Bailey’s grudges with Athletics Canada, and with many individuals from his personal and professional orbit. We are only privy to Bailey’s side of the story, so it’s hard to know how these beefs might be reciprocated. Fans of ‘Seinfeld’ might recall Festivus, and the airing of grievances.

Bailey is somewhat dismissive of his teammate Bruny Surin, who for the official record, matched Bailey’s Canadian best time of 9.84 seconds in the 100m at the 1999 world championships:

“When I thought of the competitors who might have qualified as my rivals, he wasn’t one of them. But, maybe in Athletics Canada’s eyes, I was the outsider, while Bruny was the guy who had been groomed and supported for years by a national system that was layered with executives, coaches, agents and more. They had invested in him, made him their favourite son. And I was a guy with a dominant personality, who showed up to the party late and uninvited, kicked in the door and started destroying competitions and the record books.”

Bailey appears to grow ever more comfortable positioning himself as the outsider: “I didn’t really want to fit in, ever mindful that some of these people were the same officials who’d surrounded Ben Johnson when he’d been using steroids and then disowned him and any role they’d had in his career when his drug use was discovered…I was busy rewriting the record books, undoing some of the stain he’d left behind. I was cleaning up the mess and helping Canada reclaim its place in track and field. As well, I was proud of the fact that I was a Black man creating positive news.”

Bailey’s tendency to speak his mind at the microphone draws criticism. He is attuned to the qualities of the critique. When he hears himself described as ‘arrogant’ he is well aware of racial undertones.

Loving those Saturday nights in Atlanta

‘Undisputed’ certainly delivers an insider’s look at the 1996 Olympics, when Bailey’s 100m and 4x100m wins made him the king of the world. How many remember that a torn quadriceps threw serious doubt on his ability to run? Or that Bailey was asked to be Canada’s flagbearer but could not, because of the same injury?

On the eve of the biggest race of his life, the Canadian Olympic Committee makes a surprise anti-doping visit. Bailey is incensed by the lack of trust from his own team.

Businessman Bailey gets the last word on the race that is his crowning glory:

“People ask me all the time what popped into my mind as I crossed the finish line. It’s funny. There were bonuses in my sponsorship contracts tied to winning, as well as breaking the world record and the Canadian record, which I had previously set at 9.91. I was so mindful of my athletic career being a business that once I realized I had broken the record, dollar signs flashed across my mind. Cha-ching! I had more than a few sponsors at the time, and winning gold meant a lot of money was coming my way. In the middle of all the hoopla, I was thinking about contracts and bonuses.”

His agents, with whom he has a simmering dispute, call him between his Olympic races to say they have secured $50 million in deals for him. “No!” he shouts at them. “You’re fired.”

Bailey seems a little surprised that he begins to get a reputation for being difficult to work with.

He describes his Canadian team’s relay race win:

” art of me was overjoyed to help my teammates Robert, Glenroy, Bruny and Carlton—who also received a gold medal for his participation in the earlier rounds—achieve something that would be attached to their names for the rest of their lives. It would be the only Olympic gold that any of them would win. It had been a lifelong ambition for them, and as the king, I had made it possible.”

The balance of Bailey’s athletic career cannot match the heights of 1996. He details the business thinking behind his race against American Michael Johnson at SkyDome. The head-to-head 150m dash was an unusual spectacle, which should be praised for drawing rare North American audience attention to a track event.

Injuries return to plague him, including both Achilles tendons. As the racing career winds down, so too does the health of his hugely influential and beloved mom and dad.

It is hard to avoid the impression that disputes fuel the man behind Undisputed. Toward the final pages, Bailey details his reasons for initially rejecting the Order of Canada honours which he believes were not commensurate with his achievements.

Bailey’s final self assessment is “I’ve been called brash and arrogant and many other names. Even the haters, I appreciate their support; they took the time to tell me so. I was the very best—world champion, Olympic champion, world-record holder. World’s fastest man. Undisputed.”

No matter what misgivings Undisputed might create about the geniality of its author, Donovan Bailey has ultimately delivered a bracing counter-narrative to any sense that Canadian track and field is or was perfectly managed.

He was its brightest star, but that has not dulled Bailey’s scorn for the inner workings of high performance athletics in Canada.

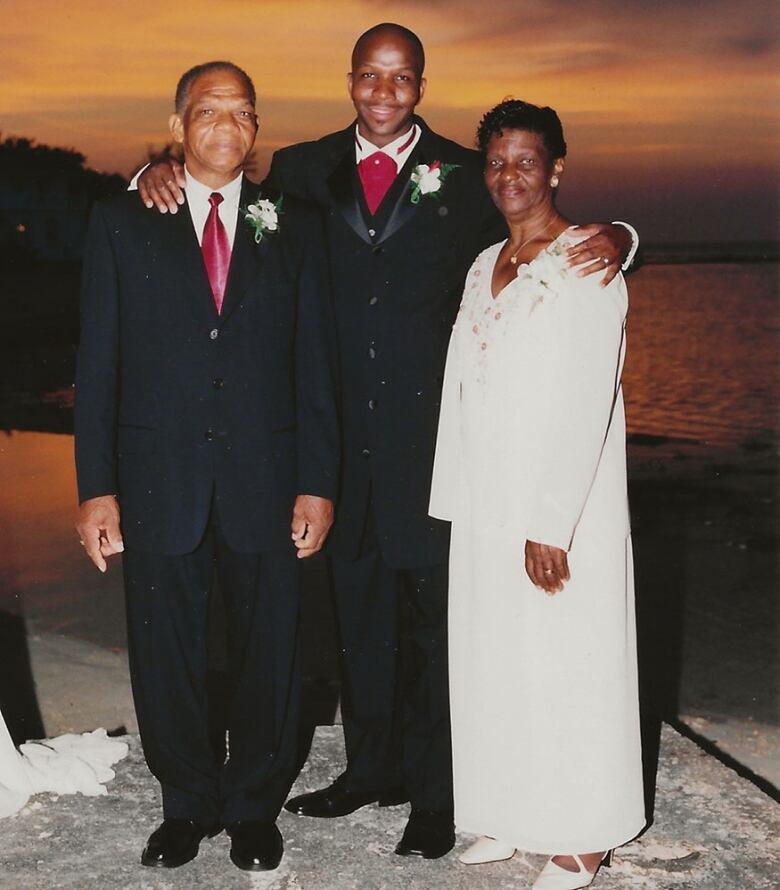

Undisputed. Donovan Bailey, Random House Canada, 272 pages, colour images, hardcover $35.

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.