The Great Train Robbery of 1963 is a crime so absurd that it effectively spawned its own genre of heist films — but you probably didn’t know that this iconic crime actually has direct ties to the big-money racing series, Formula 1. This is just one of the many crimes and scandals you’ll find in Crispian Besley’s new book, Driven to Crime: True Stories of Wrongdoing in Motor Racing.

As the name implies, Driven to Crime is a fairly straightforward book; each of its 66 chapters follows a different criminal (or victim of a crime), and many chapters feature small insets that detail some of the other fascinating scammers and swindlers of the racing world. The length of the chapter depends on the nature of the crime and the profile of the individual involved, and because the chapters are organized alphabetically by criminal or victim surname, you can pop around to read the stories that most fascinate you.

But for me, the story of Roy James was one of the most fascinating. Growing up in postwar London, James really found his niche in activities that allowed him to utilize his small, nimble frame to his advantage. On the more legitimate side of things, that meant James was great at the new sport of go-karting; on the other, it made him a fabulous cat-burglar, able to scale buildings and sneak through windows with ease. And, having come from a poor family, his criminal skills enabled him to easily earn the money he needed to compete in the expensive sport of racing.

As his racing career advanced, so did James’ criminal career. He ran into Bruce Reynolds, leader of the feared South-West Gang criminal enterprise, at a race meeting at Goodwood; James joined the gang’s fold, and he was one of several conspirators who dreamed up a plan to rob a Royal Mail train that would be carrying a large number of small bills that had been taken out of circulation.

The heist was stunning for its planning and forethought; the South-West Gang intercepted the train, unhitched several cars, and continued further down the tracks with the money-packed cars; they ultimately forced an entrapped train driver to stop at a bridge overpass where trucks were waiting to haul away what turned out to be £2.6 million in small bills. For reference, that’s £51 million, or about $64 million in today’s exchange rate.

But if you know the story, you know the South-West Gang was quickly found out. Roy James managed to flee and live on the lam for a few months, but his connection to the crime was unmistakable (his fingerprints were found on a Pyrex dish that he’d filled with milk for a cat at the gang’s hideout), and he was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

So, where’s our F1 connection? Well, James was released in 1975 for good behavior, but his ties to the racing world were still intact. His competitive skills had waned after so many years in prison, but James was able to draw on his childhood love of silversmithing to design a trophy for Bernie Ecclestone. That trophy, the Race Promoters’ Trophy, is still handed out to the best F1 promoter each year at the FIA Prize Giving Gala.

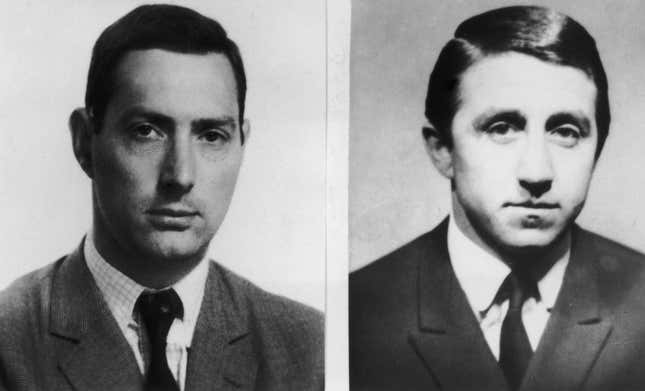

And that’s just one of the many fascinating tales in Driven to Crime. Obviously you’ll find some big names in this book: Randy Lanier and Jean-Pierre Van Rossem are two of the most notorious criminals in motorsport, but the book even details Juan Manuel Fangio’s 1958 kidnapping by Cuban revolutionaries.

Those stories are fantastic, and they absolutely deserve a place in the book — but I think Driven to Crime really shines in its more niche criminals. It’s chock full of brief interludes about club racers or aspiring team owners who fell victim to their own hubris well before their names ever reached the big time. Those folks include Jack Cottle, who was never an actual professional racer but who drove his road car onto a hot track, and Luis Fontés, whose promising career was cut short when he killed a motorcyclist while racing drunk on public roads.

I had a few minor grumps about the book; the chronological order based on surnames makes sense, but it was also a bit frustrating when reading about, say, Ted Ball before Joachim Lüthi, when it was Lüthi embezzled funds suddenly disappearing from the Brabham F1 team that opened the door for Ball to invest other fraudulent funds into the iconic outfit — ultimately leading to Brabham’s death.

Overall, Driven to Crime is a fantastic romp through some of the wildest characters that motorsport has had on offer over the years. I’d even go so far as to say it’s a must-own tome for any racing fan, no matter how casual; racing’s long history of crime and scandal certainly helps contextualize many more modern concerns, like Rich Energy’s sponsorship of Haas’ F1 team (and yes, team owner Gene Haas makes an appearance in Driven to Crime). Once you understand that very smart people have been falling for false pretenses for decades, you come to better understand why similar problems can happen today.