Confirmed attendees include senior Hong Kong officials like Paul Chan Mo-po, the financial secretary, and Wong Chuen-fai, the city’s climate change commissioner. Senior officials and experts from Guangdong province as well as representatives from Los Angeles, Berkeley, San Francisco and other cities are also expected to participate.

It follows a visit to China in October by California Governor Gavin Newsom, who signed five climate-cooperation agreements with authorities in Guangdong and Jiangsu provinces and with their counterparts in Beijing and Shanghai.

The talks, slated to concentrate on industrial decarbonisation, carbon markets and clean energy deployment – topics pinpointed during Newsom’s visit – will be the first since US President Joe Biden announced substantial tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, solar panels and lithium-ion batteries.

The action, which Beijing condemned as “self-defeating” and “contrary” to the consensus reached between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Biden in a joint climate response in November, came days after the first in-person meeting between China’s special climate envoy, Liu Zhenmin, and White House senior adviser John Podesta in Washington this month.

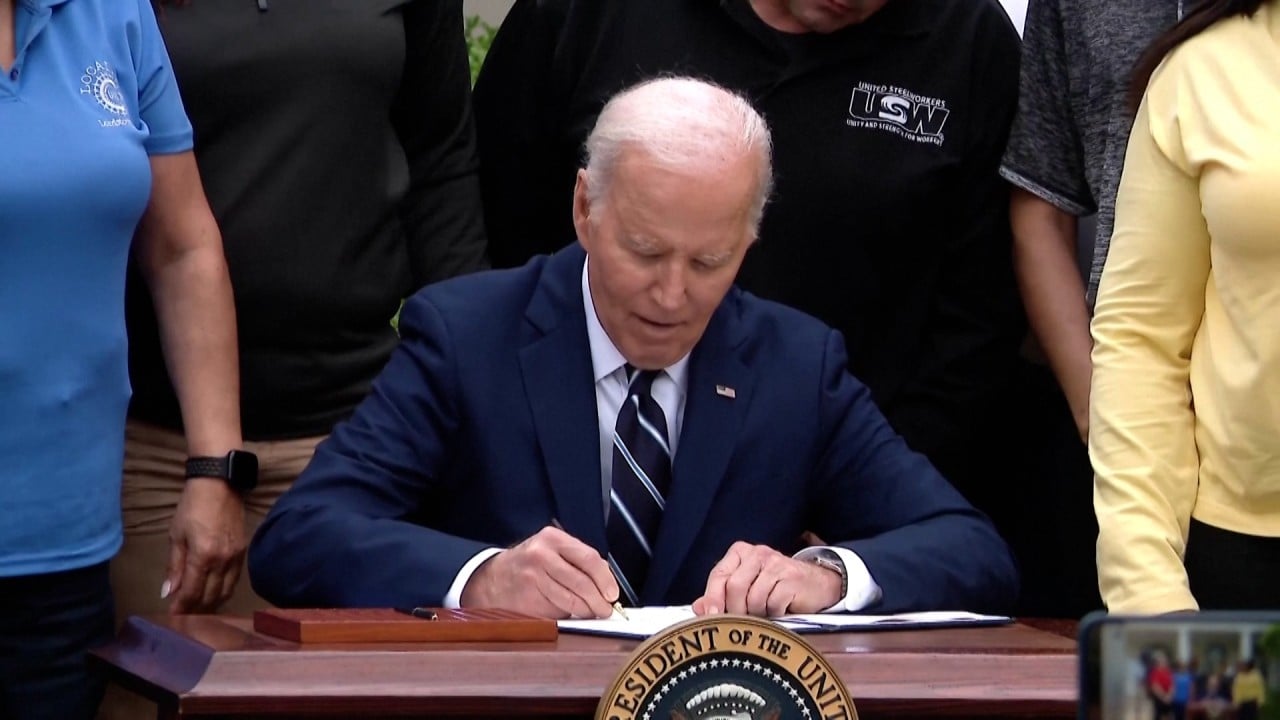

After seemingly friendly bilateral talks on May 8-9, where both sides pledged to enhance renewables and increase technical exchanges, Biden imposed a 100 per cent tariff on Chinese electric vehicles. He said Beijing was flooding global markets with underpriced exports, and he doubled import duties on Chinese solar panels to 50 per cent, tripled them on Chinese steel and aluminium to 25 per cent and raised tariffs on lithium-ion EV batteries to over 25 per cent.

When asked if the talks and tariffs could coexist, Liu Pengyu, spokesman for the Chinese embassy in Washington, said the US should “stop repairing and digging up the road at the same time” and “create enabling conditions for China-US climate cooperation and global green transition”.

This was a stark departure from the optimism following the Liu-Podesta meeting, when China’s ambassador to the US Xie Feng expressed anticipation for the California event. “Both sides look forward to it,” he wrote on X, formerly Twitter, adding, “A further step to turn the San Francisco vision into reality!”

But according to Jennifer Turner, director of the China Environment Forum at the Wilson Centre, a think tank in Washington, despite the “trying times”, the upcoming talks will not be directly affected by the renewed tensions over EVs and solar panels.

She said that climate talks encompass more than just electric vehicles and sensitive technology sharing. “Cities and states are also coming together to discuss policy, regulation and monitoring,” she noted, referencing areas such as carbon markets, methane reduction and advancements in agriculture.

Turner suggested that the expansive realm of climate issues still provided ample opportunities for China and the US to discover common ground and engage in “mutual learning”.

She noted the inherent contradictions in the relationship, adding that despite potential conflicts, discussions on global health, climate and the environment, as well as combating the illegal wildlife trade, have persisted.

Amid geopolitical tensions in November 2021, the two countries surprised the world with a rare joint declaration, recalling their “firm commitment to work together” to achieve the 1.5 degree Celsius temperature goal set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

This success, however, proved fleeting. Beijing suspended all cooperation on the issue in August 2022 after then US House speaker Nancy Pelosi made an official trip to Taiwan. China’s top diplomat Wang Yi stated that “climate cannot be an oasis surrounded by the desert”.

Kelly Sims Gallagher, who served as a senior adviser on Chinese climate matters in US president Barack Obama’s administration, told The Washington Post in May 2023 that climate was “understood by China to be something the US wants, and it’s using climate as a source of leverage in the multifaceted relationship”.

Another breakthrough was achieved in November, with Xi and Biden agreeing to restart climate change talks, along with a meeting between their climate envoys in California.

Taylah Bland, a fellow on climate and the environment with the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Centre for China Analysis think tank, said “the implementation of tariffs reinforces the difficulties of reconciling issues of climate, trade and economic competition”.

She added that there was an “inevitable climate price” associated with the tariffs, which highlight the “challenges faced by the global climate agenda when major powers are engaged in a fierce geopolitical competition”.

Bland noted that although these measures might impede the pace of the energy transition, it remains crucial for both countries to “not stop engagement on other critical issues of climate like subnational cooperation, adaptation and resilience”.

According to Thibault Denamiel of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington, the tariffs “symbolise another step towards trade fragmentation which will inevitably spill over into the two nations’ ability to collaborate on broader issues” like climate.

“I would argue that the ship had already sailed – but with these tariffs, it’s sailing further away,” he said, forecasting that while talks may persist in the near future, they are unlikely to produce significant results unless both nations take complementary strides toward decarbonising their economies.

Wilson Centre’s Turner pointed out that China initiated subsidies for solar panels several years ago, eventually supplying over 80 per cent of the global market. “But they made it competitive against subsidised coal and gas around the world. The world is in some ways indebted to China,” she said.

Henry Lee, director of the environment and natural resources programme at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs, acknowledged that bringing in cheaper electric vehicles could cut down carbon emissions. But he viewed the newly imposed tariffs as a “short-term setback” for the climate.

“Allowing millions of Chinese EVs into the market at this time would endanger the progress that US manufacturers have made and are poised to make,” Lee said, adding that climate was an “existential issue” that required the two countries to increase dialogue – both at the government-to-government and informal Track 2 levels – regardless of government policies on “selective issues”.

“If the two countries can listen and learn from each other, then there is a much greater chance that cooperation between the two countries can grow,” he said.

Michael Davidson of the University of California San Diego, who specialises in studying the practical challenges involved in large-scale renewable energy deployment, believes that “deploying enough clean tech to meet climate goals will rely upon both collaboration and competition between the US and China”.

He said Western policymakers must strike a balance between shielding their producers as they scale up to compete with Chinese firms, while also considering potential setbacks caused by higher prices because of delays.

As awareness of the need for deployment grows, alongside the political imperative to uphold robust climate ambitions, Davidson anticipates that there will be opportunities for discussions regarding regulatory frameworks.

He said that as more countries emulate China’s approach in bolstering their clean tech industrial policies, the two sides should have more opportunities for conversations on the “rules of the road”.