But the journey has been far from smooth. The starship model and its celebrated return are now the subject of a lawsuit alleging fraud, negligence and deceptive trade practice, highlighting the enduring value of memorabilia from the sci-fi television series.

The case was brought by Dustin Riach and Jason Rivas, long-time friends and self-described storage unit entrepreneurs who discovered the model among a stash of items they bought “sight unseen” from a lien sale at a storage locker in Los Angeles in October 2023.

A lien is a legal claim on property held as debt collateral. Failure to pay the debt back means the lender or creditor has the right to seize or sell the property.

“It’s an unfortunate misunderstanding. We have a seller on one side and a buyer on the other side and Heritage is in the middle, and we are aligning the parties on both sides to get the transaction complete,” says Armen Vartian, a lawyer representing the auction house, adding that the allegations against his client were “unfounded”.

The pair claimed that once the model was authenticated and given a value of US$800,000, they agreed to consign it to an auction sale with Heritage planned for July 2024, according to the lawsuit.

However, following their agreement, they allege the auction house falsely questioned their title to the model and then convinced them, instead of taking it to auction, to sell it for a lowball US$500,000 to Roddenberry Entertainment.

According to the suit, Eugene Roddenberry, the company’s CEO, had shown great interest in the model and could potentially provide a pipeline of memorabilia to the auction house in the future.

“They think we have a disagreement with Roddenberry,” says Dale Washington, Riach and Rivas’ lawyer. “We don’t. We think they violated property law in the discharge of their fiduciary duties.”

The two men allege they have yet to receive the US$500,000 payment.

“It’s a roll of dice in the dark,” Riach says of his profession bidding on storage lockers. “Sometimes you are buying a picture of a unit. When a unit goes to lien, what you see is what you get and the rest is a surprise. At a live auction, you can shine a flashlight, smell and look inside to get a gauge. But online is a gamble, it’s only as good as the photo.”

Last autumn, Riach says he saw a picture of a large locker in an online sale. It was 10 feet by 30 feet (three metres by nine metres), and “I saw boxes hiding in the back, it was dirty, dusty, there were cobwebs and what looked like a bunch of broken furniture,” he says.

Something about it, he says “looked interesting”, and he called Rivas and told him they should bid on it. Riach declined to say how much they paid.

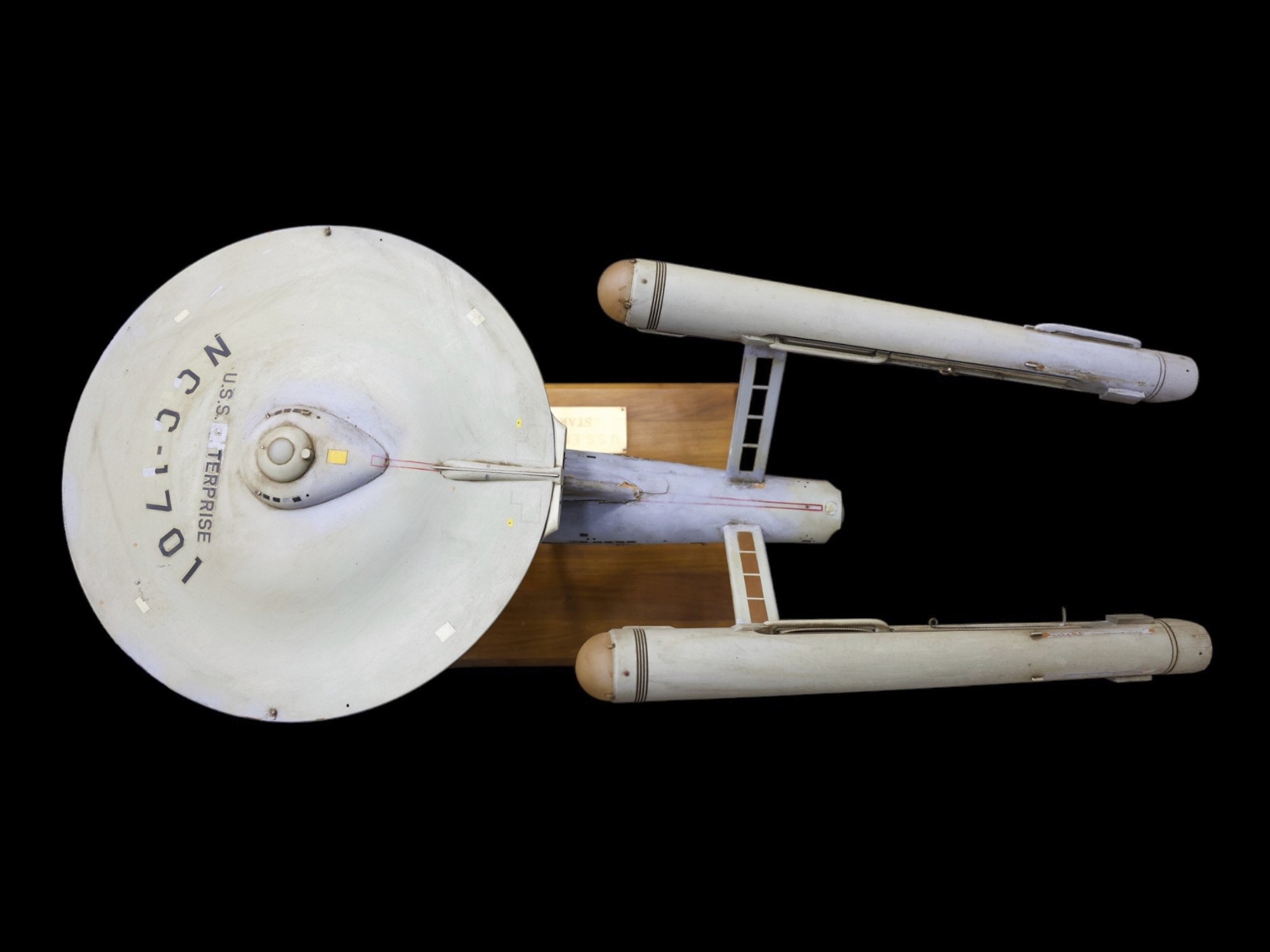

There were tins of old photographs and negatives of nitrate film reels from the 1800s and 1900s. When Rivas unwrapped a rubbish bag that was sitting on top of furniture, he pulled out a model of a spaceship. The business card of its maker, Richard C. Datin, was affixed to the bottom of the base.

A Google search turned up that Datin had made Star Trek models, although the two men did not make the connection to the television series.

“We buy lots of units and see models all of the time,” Riach says. He thought they would find a buyer and decided to list it on eBay with a starting price of US$1,000.

At once, they were deluged with inquiries. Among Trekkies, the long-lost first starship model had attained a mythical status.

In 2022, at a Heritage auction of 75 props and items, a Starfleet Communicator from the 1990s series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine sold for US$27,500 while a pair of Spock’s prosthetic Vulcan ear tips from the original series went for US$11,875, more than twice the amount they brought when they were sold in 2017 for US$5,100.

There are people buying storage units for 20 years and you will never find anything this great. It’s like buying a lottery ticket. It was a very great find

The starship’s design was crucial to the series’ success. “If you didn’t believe you were in a vehicle travelling through space, a vehicle that made sense, whose layout and design made sense, then you wouldn’t believe in the series,” Gene Roddenberry said in the 1968 book The Making of Star Trek, according to the auction house.

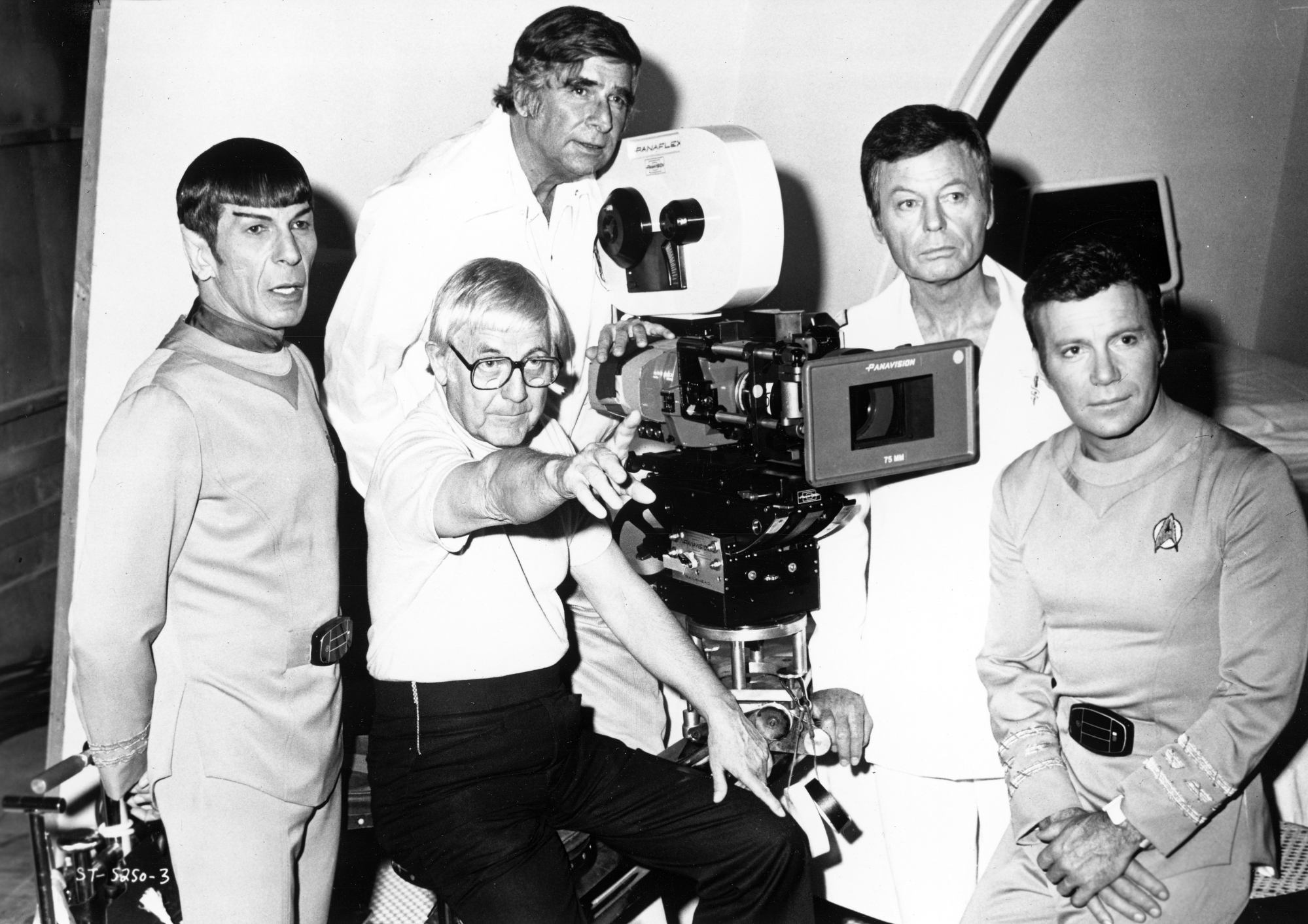

For years, the show’s creator had kept the 33-inch model on his desk. It became the prototype for the 11-foot model used in subsequent episodes. That version was later donated to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington in the US. But that first model disappeared around 1978 when the makers of Star Trek: The Motion Picture borrowed it.

“My problem is simply that of getting my model back,” Roddenberry wrote, according to a copy provided by Washington. “It is a fairly expensive piece of model making but its real value to me is what it represents.” He added that no one he had spoken with “had the slightest hint as to who got it or what happened to it”.

Roddenberry died in 1991.

After the massive interest sparked by the eBay listing, Riach and Rivas pulled the sale and began researching the model more intently. They discovered the connection between Datin and the television series but also learned that the original model was the same size as the one they had found and it had gone missing.

“I said wow, do we have something here?” says Riach, and then reached out to Heritage.

But given the treasure he unearthed, he now says, “I love Star Trek.”

“There are people buying storage units for 20 years and you will never find anything this great,” he says. “It’s like buying a lottery ticket. It was a very great find.”

Things took an unexpected twist, Riach says. In March, he and Rivas signed an agreement to sell the model for US$500,000 after it was pulled from the planned auction and they were told Roddenberry Entertainment had a “strong claim” to the model’s title and “would tie them up with its ‘powerful legal team’.”

But then they were given a new transfer agreement to sign with a new set of terms. Riach declined and, instead, he and Rivas called Washington.

Heritage “moved the goalposts”, according to their lawyer. Under the new agreement, Riach and Rivas would be paid a “finder’s fee”, which Washington called a “reward”, converting it from a transactional payment to a potentially voluntary payment.

They said that by April, when Heritage announced the model had resurfaced, they came to believe the house failed to disclose the item’s value was much greater than they had been told.

Joe Maddalena, Heritage’s executive vice-president, made public statements calling it “priceless”.

“It could sell for any amount and I wouldn’t be surprised because of what it is,” he says. “It is truly a cultural icon.”

They also had not been paid.

On April 28, 10 days after Heritage announced it had returned the model to Roddenberry, Riach and Rivas’ lawyer sent a letter to the auction house’s lawyer outlining their claims and asking for the payment promised; they also proposed mediation.

Vartian, the lawyer representing Heritage, said that Riach and Rivas became “impatient” about getting the transaction done, and disputes the house had a fiduciary duty to them.

“This is an arm’s-length business relationship,” Vartian says. “They bring something to the auction house and are trying to get the most possible amount as quickly as possible, that is [Heritage’s] position and what they did.”

Still, Vartian is confident that they will soon conclude the transaction, saying: “Various things including scheduling have taken longer than [they should].”

For his part, Riach says this experience is much like that of the crew of the USS Enterprise – “a strange new world”.

“I’ve never experienced anything like this. I’ve sold fine art at auction and other places, I got my cheque and went on. I’ve never had this roller coaster.”

“Storage is a hard game. Sometimes you win and sometimes you lose,” he adds. “We’ve bought a US$10,000 unit and everything was complete garbage. But if you play long enough, you can get lucky.”