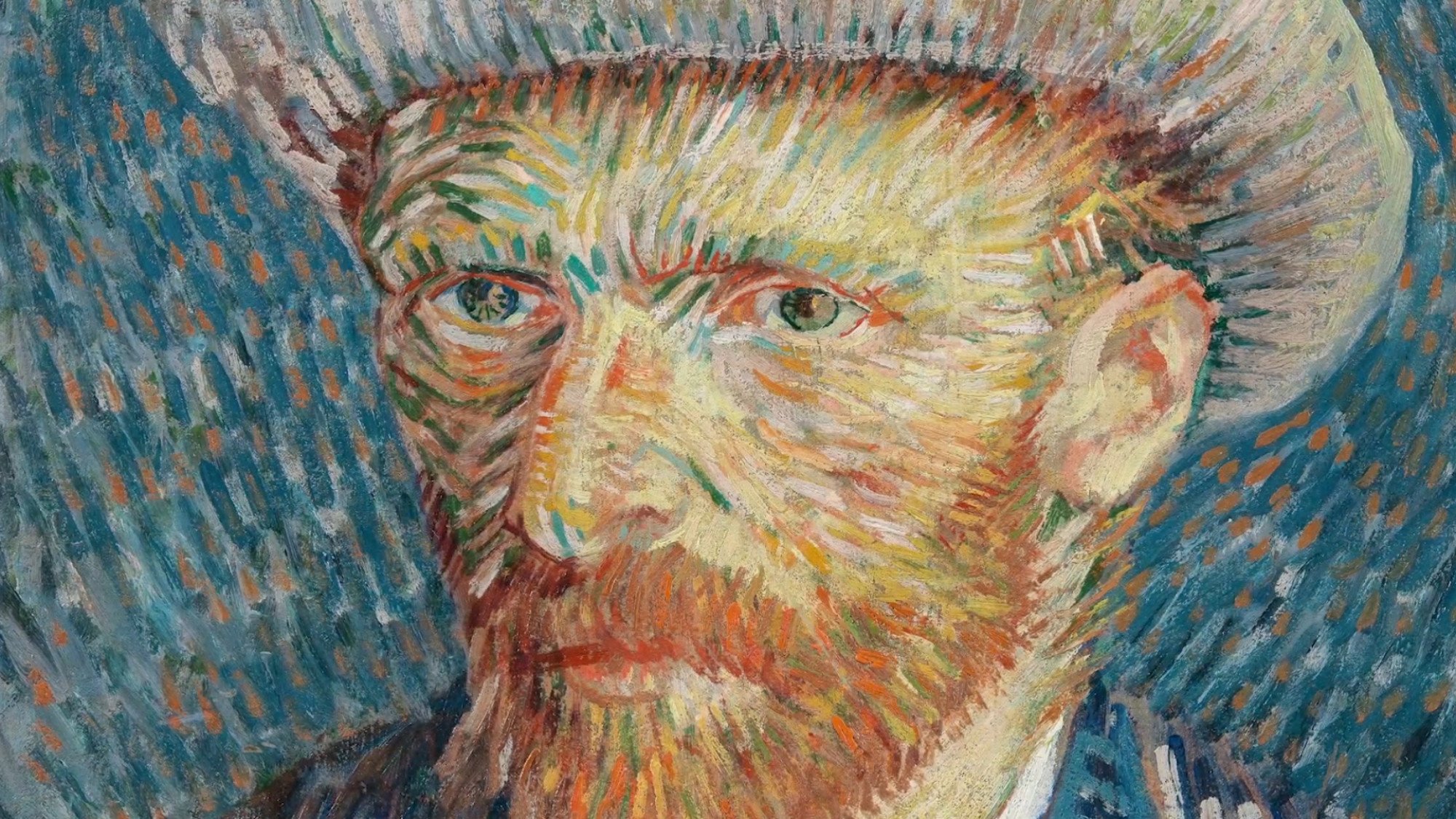

Inspired by a joint exhibition of works by Vincent van Gogh and Gustav Klimt at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum in 2015, the ensemble’s chief conductor, Peter Dijkstra, and artistic director, Tido Visser, put together a musical playlist that pricked similar responses in the ear, using works by Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Satie, Schoenberg, Richard Strauss and a thoughtful pairing of pieces by Gustav and Alma Mahler.

From there, the project went into the hands of Fuse, a multimedia art studio that uses technology “to interpret the complexity of human and natural phenomena” – a description in the programme book that couldn’t describe its role here any better.

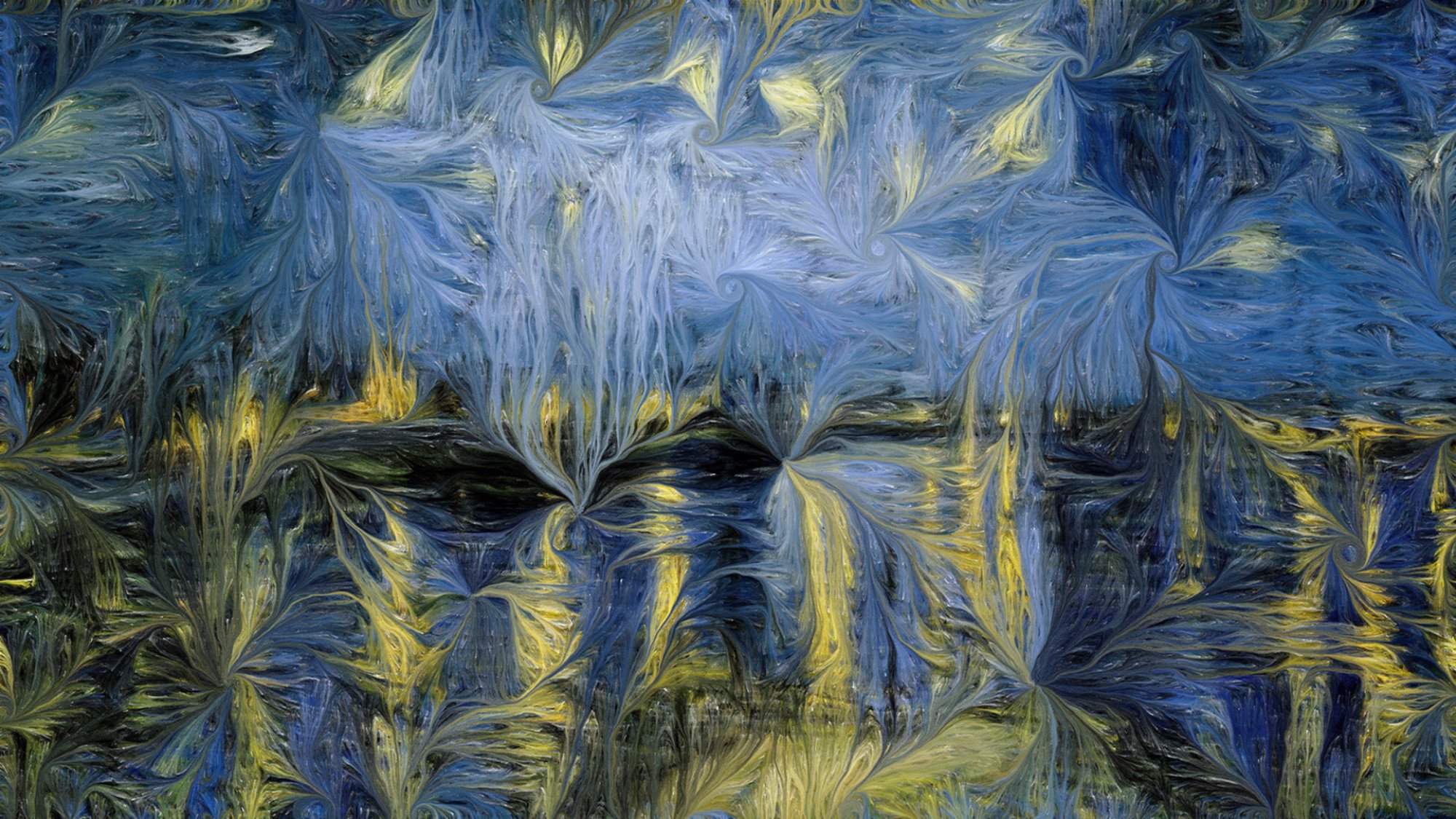

On stage, the 32-member chorus sang in front of a V-shaped dual projection screen displaying familiar museum images by Van Gogh, then Klimt. Throughout the performance, both the voices and breath of the singers, as well as the physical gestures of Dijkstra’s conducting, were incorporated into an algorithm that deconstructed the artists’ works as a living video.

‘I hated being called a prodigy’: Alma Deutscher, 18, composer and musician

‘I hated being called a prodigy’: Alma Deutscher, 18, composer and musician

On a purely musical level, the results were riveting. On the French side, Saint-Saëns’s Two Choruses from Op. 68 moved seamlessly into Debussy’s Trois chansons de Charles d’Orleans (his only work for unaccompanied voices) and arrangements of a solo song and piano prelude by Clytus Gottwald.

It then settled into an inspired vocal arrangement of Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1 by William Knight, incorporating the text by Spanish poet JP Contamine de Latour that inspired Satie’s solo piano work.

From the Austro-German side came choral arrangements of works by Alma and Gustav Mahler – the wife was famously overshadowed both personally and professionally by her husband – neither of whom wrote directly for chorus.

Under Gottwald’s settings, a far greater affinity for text was revealed in two of Alma’s Three Early Songs, while a more complete musical vision was displayed in an a cappella rendition of Gustav’s Adagietto from his Fifth Symphony.

Richard Strauss’s Traumlicht (“Dreamlight”) for male chorus smoothly melded into Schoenberg’s Three Times a Thousand Years and Peace on Earth, two works that taken together chart the composer’s move away from quasi-Mahlerian tonal richness into disregarding tonality altogether.

In trying to highlight the similarity between music and visual arts, “Van Gogh in Me” also reveals a fundamental difference. Where a painter is concerned with filling a space, a musical vision is measured in duration. Hauling a freeze-frame into life hardly respects the focus and integrity that a visual artist puts into crystallising a moment in time.

And yet, on a higher level, last weekend’s programme offered a sense of completion. Both the music and visuals involved chart the end of a specific era, where 19th-century social, political and aesthetic values dissolved beyond all recognition.

Historians would realise this only after Europe was torn apart by war; artists had been attuned to the situation for some time. Watching iconic images being digitally torn apart to a corresponding soundtrack arguably discounts the painter’s personal vision, but it rather gets to the point.

A major lapse, however, came in ignoring the artistic step in-between. Writers, like musicians, also need time to fit a vocabulary to a vision. Music – and choral music in particular – becomes the next step in filling in what the words leave out.

Although the evening’s substantial text was well documented and translated in the programme book, the performance itself took place in a darkened room. For a multimedia performance whose very meaning was to show artistic relationships in real time, not incorporating the texts into the projections was a significant omission.