A typical electrolyser uses 9kg of water to make 1kg of hydrogen, with the remaining 8kg released as oxygen. In a standard fuel cell, for every kilogram of hydrogen consumed, 9kg of water is released. A sustainable source of water is a key determinant for siting green hydrogen production projects. Availability of abundant cheap renewable energy is another.

Why are electrolysers and fuel cells important for climate mitigation?

In power plants, a small percentage of green hydrogen can be blended with natural gas without equipment modification to reduce the plants’ carbon intensity. A hydrogen blending ratio in excess of 50 per cent requires equipment retrofitting, according to Finnish energy and marine tech firm Wartsila.

In steel plants, hydrogen can be used as an oxidising agent to produce low-carbon steel. Pilot projects are being built in many countries.

In transport, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles have been in use for more than two decades, with some 14,500 units sold worldwide last year, according to SNE Research. Recently, some ships have started using fuel blended with hydrogen derivatives like methanol and ammonia to lower emissions.

Ultimately, the climate mitigation benefits generated by the adoption of green hydrogen will depend on the pace of cost reduction and production and supply chain development. These will depend on government policies and technology advancement.

Is the technology behind electrolysers and fuel cells new?

The first electrolysers and fuel cells were invented in the 19th century. Commercial application of electrolysis was rare since hydrogen has for decades been made cheaply with fossil fuels, through the reaction of natural gas or coal with steam, a highly carbon-intensive process.

Industrial use of fuel cells came many decades later to generate electricity for off-grid applications, such as space expeditions and satellites. These were followed by power backups for buildings and in remote areas, and transport.

Commercial production of green hydrogen only started around five years ago as a key decarbonisation and clean energy storage solution for the future, according to Assaf Sayada, CEO of Israel-based Hydro X, which is seeking to commercialise its know-how to safely transport the low carbon fuel.

“The world understands there is absolutely no way to reach the decarbonisation objective of the planet without a major role played by green hydrogen,” he said.

What are the main electrolysis technologies available on the market?

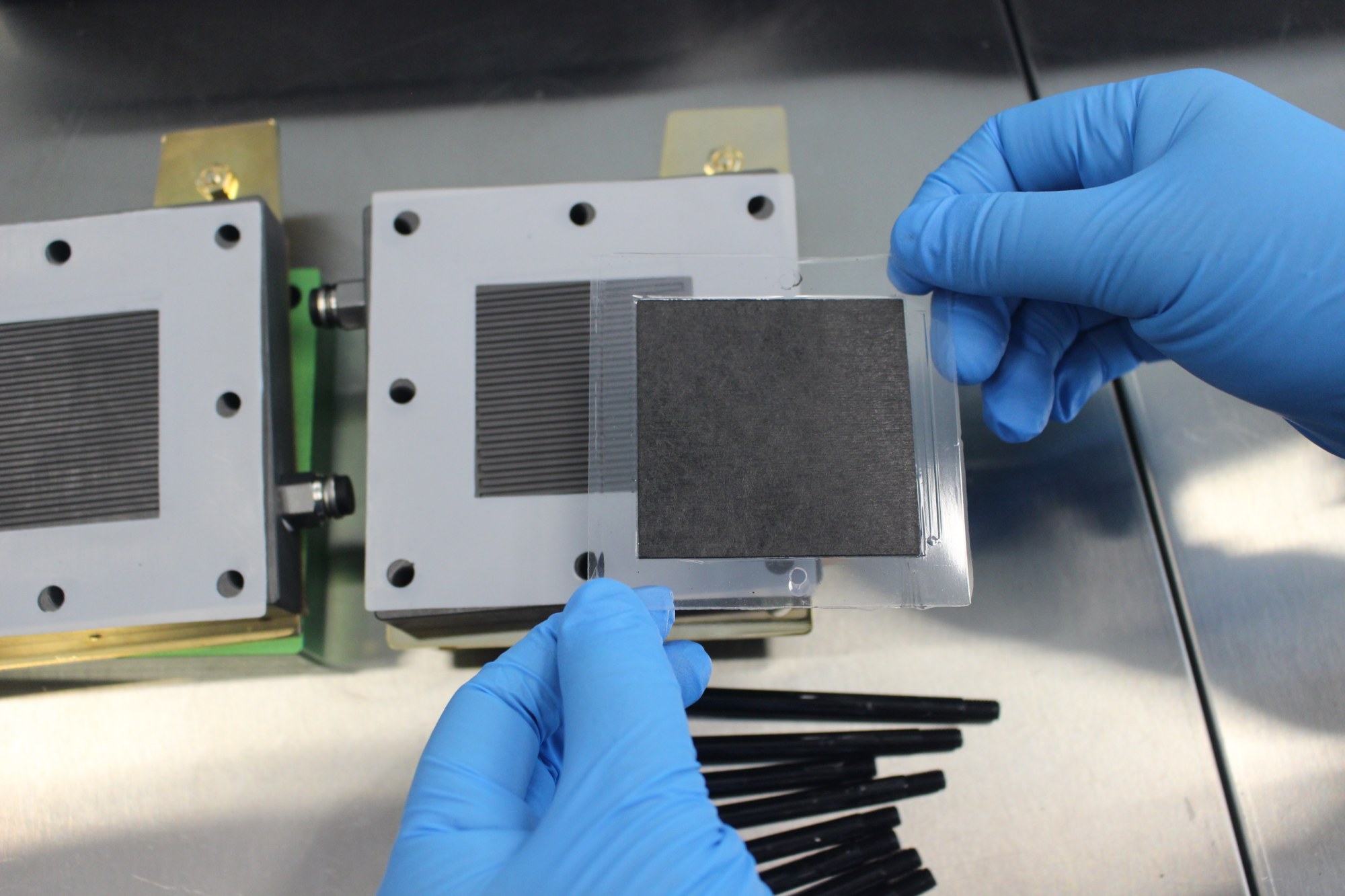

Alkaline and proton exchange membrane (PEM) are the two main commercially available technologies.

Solid oxide electrolysis (SOEC) is close to commercialisation, while anion exchange membrane (AEM) is still in the early stages of development.

Alkaline electrolysers were first used over 100 years ago for producing ammonia – a key fertiliser ingredient – using hydropower. Hydrogen is first produced from natural gas, before it is mixed with nitrogen to produce ammonia, under extreme heat, pressure and in the presence of a catalyst.

PEM electrolysers were developed in the 1960s by General Electric for space applications to generate oxygen for astronaut life support. Subsequently, they were used to make hydrogen commercially for industrial applications, such as petroleum refining, glass and metals production.

What are the pros and cons of the electrolysers using the two mainstream technologies?

A precious metal like platinum or iridium has to be used as a catalyst in PEM electrolysers, while nickel can be used in alkaline ones.

However, PEM electrolysers can operate effectively at high current densities – the amount of electric current travelling per unit cross-section area – and can adapt to rapid changes in power levels. This makes them more suitable for deployment with renewable energy, whose supply can be intermittent and varies with the weather.

Which electrolyser is likely to dominate the green hydrogen market?

Alkaline electrolysers are more likely to dominate China’s green hydrogen market than PEM electrolysers, which are more common in Europe and the US, according to Amily Guo, China refining and chemicals analyst at UBS.

This is because the cost of alkaline electrolysers in China has fallen to a third that of the PEM type, making them more attractive for large green hydrogen projects being built in the nation’s renewable energy-rich northern regions.

However, Guo expects the price difference between the two types to narrow after 2030 as the technology continues to advance, allowing PEM products to gain market share in China.

Currently, the cost of coal-derived “grey” hydrogen is about 10 yuan (US$4.10) per kg, she noted. There is still a substantial gap compared with 30 yuan per kg of green hydrogen made by alkaline electrolysers and 25 yuan per kg produced by PEM ones, which means financial incentives are needed for adoption of the green option.