The pair took on the name Zheng Mahler as an alias in 2014, after they were commissioned for a sensitive research project by the Johann Jacobs Museum in Zurich, Switzerland, about trade between Africa and Asia.

Bisenieks had previously done anthropological research on the local economies in Kenya, while Ng had a familial attachment to Africa – his mother’s family had emigrated from China to Mozambique in the 19th century and lived there until the 1970s, when the Mozambican Civil War dispersed the family to different Portuguese-speaking colonies around the world.

‘It’s about deceleration’: time seems to slow in live performance art show

‘It’s about deceleration’: time seems to slow in live performance art show

“The curious thing is, because most Chinese in the 19th century who emigrated out of China were going to gold-mining destinations – South Africa, Australia, San Francisco, California – no one knows [why they moved to Mozambique],” Ng says. “I think they probably just took the wrong ship and said all right, I’m stuck here.”

As part of their research, the pair came across the book Ghetto at the Centre of the World: Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong, an ethnography by Hong Kong-based American anthropologist Gordon Mathews. And that’s what took them to Hong Kong, with Chungking Mansions, the labyrinthine, covert nerve centre of trade between China and sub-Saharan Africa, playing a major role in their three-year project.

The first exhibition based on the project, called “A Season in Shell”, included a two-channel video, sculptures made with abalone shells, a poem, and a performance that was a shared meal of Somali abalone cooked by a Chinese chef in Zurich.

Zheng Mahler had worked closely with a Somali trader and asylum seeker who ran an abalone export business in Hong Kong.

“He had seen that abalone was a delicacy in seafood restaurants here, and realised that where he was from, Somalia, which has the Red Sea coast, is full of abalone, but nobody eats it,” Ng explains.

“One really interesting aspect was, he was selling the abalone here [in Hong Kong], but he was also collecting the abalone shells because one side is mother of pearl,” Ng adds. He sent the empty shells to be processed in China and then sold them in Switzerland, where mother of pearl is used in watchmaking.

Because of the sensitive nature of their research – asylum seekers are not legally allowed to work in Hong Kong – Ng and Bisenieks began to fake their names, with Ng taking the name Royce Zheng and Bisenieks taking on Daisy Mahler.

“We suspect she was very protective of [the fact] that she was Jewish, actually. She disguised her name to find safety, to get out of Europe,” Bisenieks says. “I wanted to reinvigorate, revive it as my kind of protection as well.”

In 2020, the pair were invited to participate in Para Site’s “Liquid Ground” exhibition (shown in 2021), which resulted in the first of Zheng Mahler’s multi-species, sensory ethnographies based on the ecosystems of Lantau.

The duo parlayed Bisenieks’ master’s thesis research into a work titled Bubalus Bubalis 14-40,000hz, based on the hearing of the island’s free-roaming water buffaloes and the way the animals navigate and terraform the Lantau landscape into biodiverse wetland.

For the piece, the duo built an ultrasonic binaural microphone with 3D-printed buffalo ears, and walked through typical water buffalo paths while making field recordings.

Artists bare intimate personal memories on Hong Kong’s most public stage

Artists bare intimate personal memories on Hong Kong’s most public stage

The resulting installation presented the ultrasonic frequencies – sound waves and vibrations – that water buffalo can hear in a visual manner, while the frequencies within human hearing range were played via headphones.

“The different sensory perception and the relationship with the space, as opposed to humans, [is fascinating],” Bisenieks says. “We wanted to bring attention to that as a way to consider how we might live with the land, and the importance of other creatures and their relationship with the land.”

The same year “Liquid Ground” opened, the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (IFA), a German cultural and educational relations body, commissioned the pair to create an online project centring on artists’ relationship with technology.

There’s a whole field in virtual reality at the moment of animal embodiment

The topic fit squarely into Zheng Mahler’s oeuvre – their work had become increasingly digital starting from 2016, when Ng began teaching himself how to create 3D animations, digital renderings and virtual reality design.

In examining their immediate surroundings, Ng and Bisenieks quickly settled on bats as a point of interest for their IFA commission, for which the resulting animation, What is it like to be a (virtual) bat?, was shown online and became the central work of the eponymous exhibition at PHD Group.

It was named after a famous 1974 paper by American philosopher Thomas Nagel, “What is it like to be a bat?”, a key reference that prompted questions about understanding another being’s consciousness, and experiencing the world through senses beyond the usual perspectives.

“There’s a whole field in virtual reality at the moment of animal embodiment, where basically, researchers put people in the body of different animals. You can become a hummingbird or a turtle or a cow,” Ng says.

“If you simulate, with technology, the sensory apparatus of a bat, does it bring you any closer to experiencing what it’s like to be a bat? That’s the central question of the exhibition.

“The interesting thing, with the buffalo project and the bat project, for me at least, is how technology can be used to mediate between the human and the more-than-human or non-human sensors,” he adds.

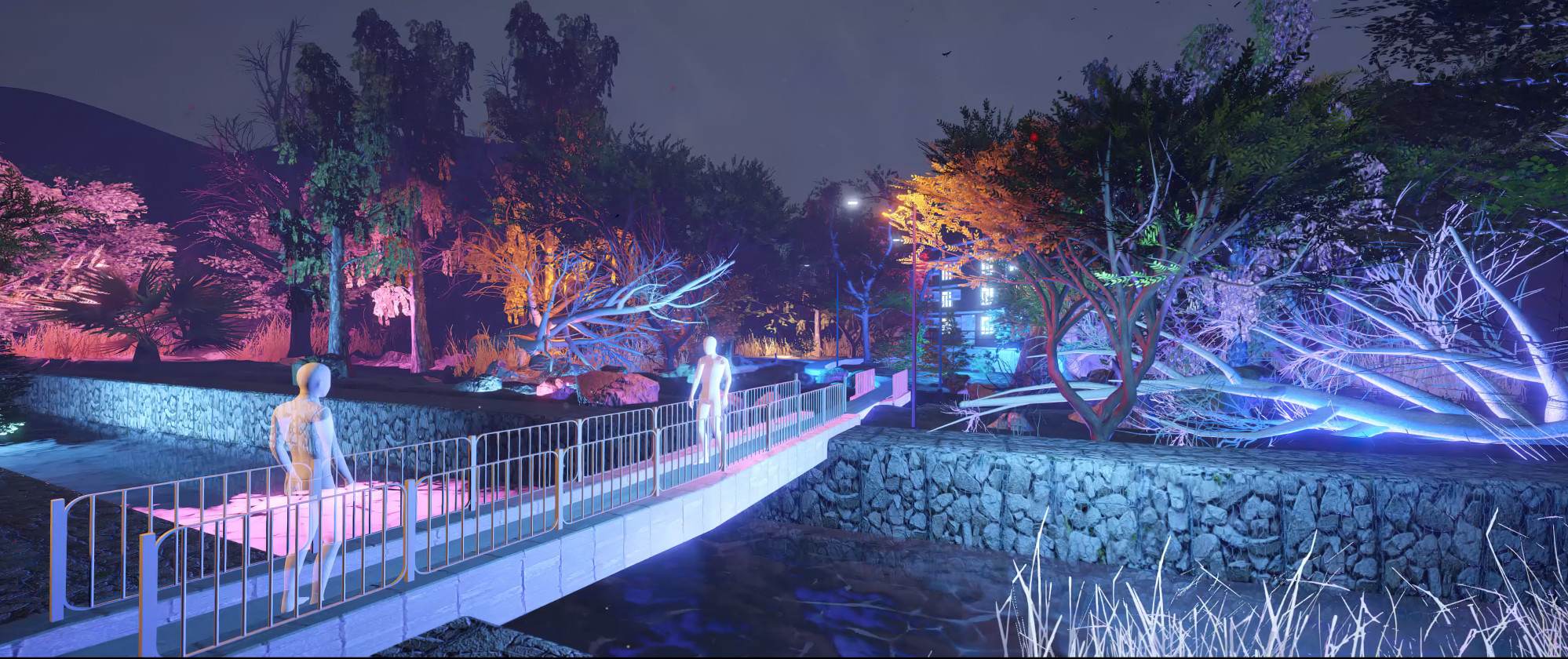

To realise the work – an animation that prompts the audience to transform from an avatar to a bat, which then flies through Mui Wo – Ng and Bisenieks conducted a field survey, using ultrasonic microphones to record sounds, and thermal cameras to capture thermal imaging and flight patterns of their neighbourhood bats.

At PHD Group, there is an option to view the animation on a large screen, and another to immerse yourself in the same world, but through virtual reality. One of the conceptual underpinnings of the work is that the human and the animal are not distinct, and entering the virtual reality experience is akin to entering an altered state of consciousness – perhaps, like in some practices, discovering the animal inside the human, Ng says.

“[The VR experience] performs closest to a guided meditation, where the viewer is taken through this journey of walking down this little village path, which is in our neighbourhood, and then kind of dissolving into this … landscape, moving skyward,” Bisenieks says.

The experience also involves a sensory shift, from a visual to a sonic world, where the ultraviolet colouring reflects the sensory intensity of the sound and the bats’ sensitivities to light.

As part of the exhibition, there is a smaller video of bat flight – shown via a moving point cloud – on a smaller screen, which Ng created using LiDAR, a remote sensing method used to measure the distance between, and movement of, any objectionable hits.

“It’s kind of a human parallel to what a bat does with sound,” Ng says.

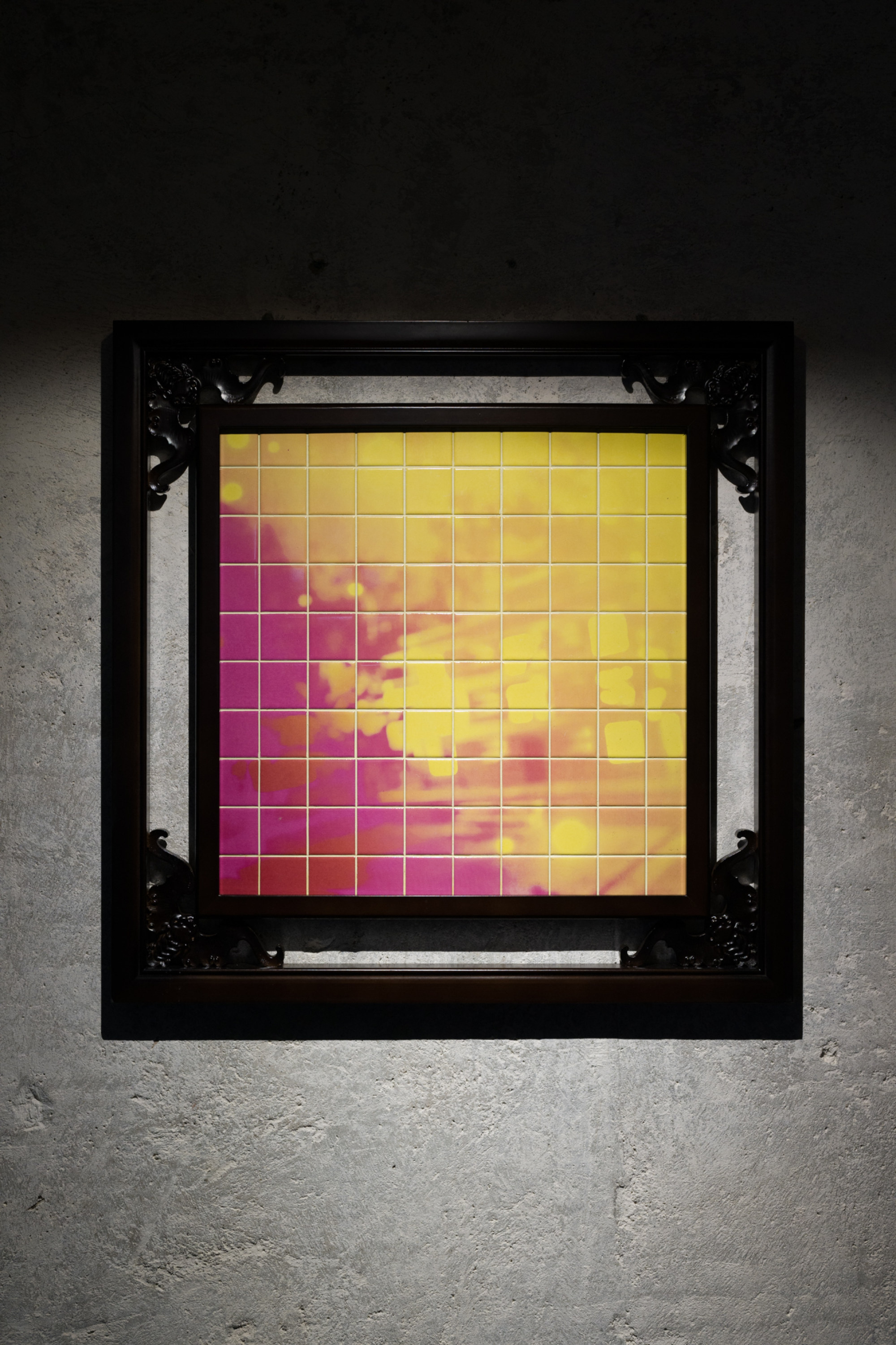

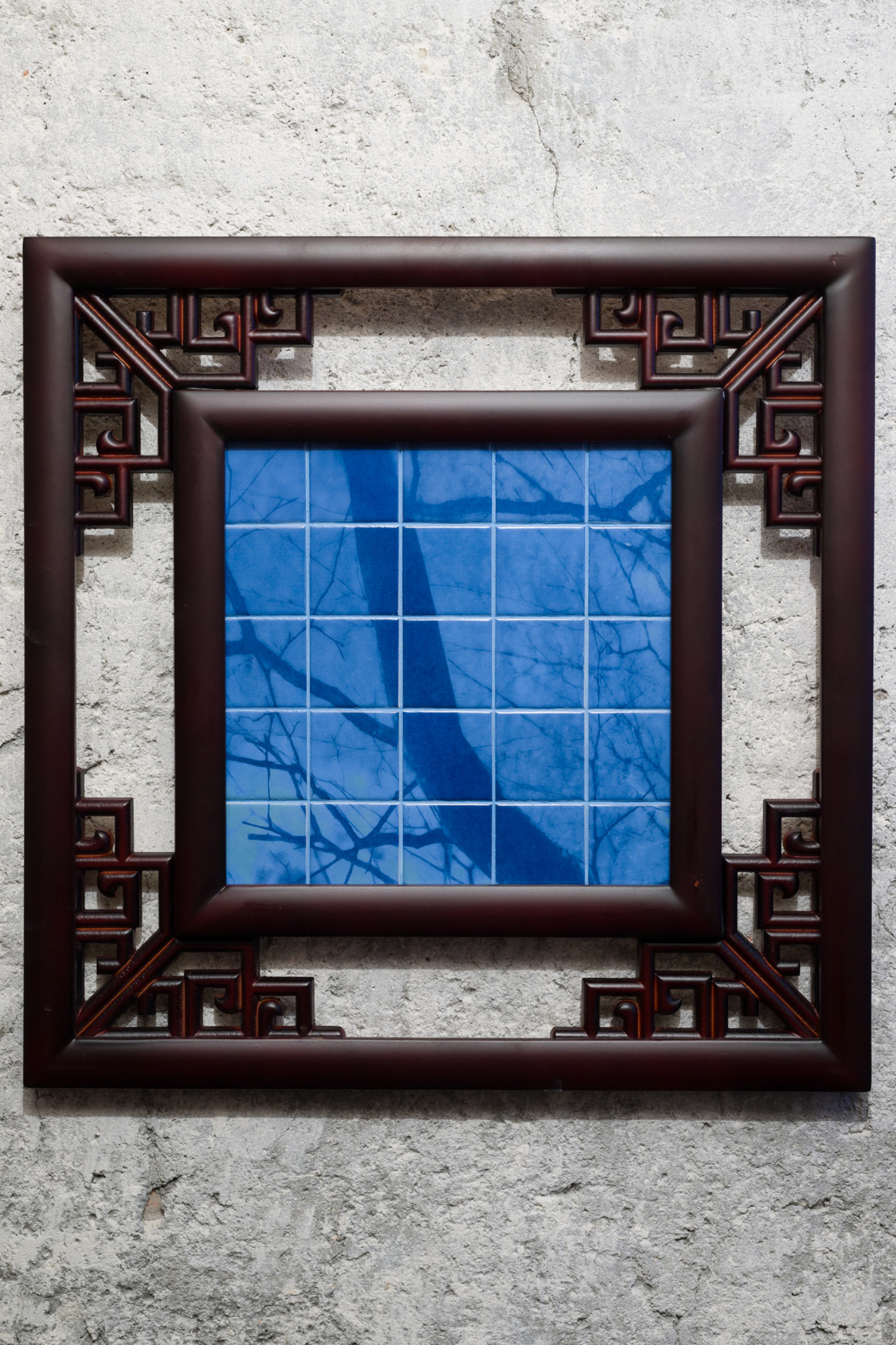

Inspired by a mosaic of bats outside a temple in Mui Wo, Zheng Mahler is also showing a number of tiled mosaics, which feature screen-printed images taken from the main animation and act as visual aids for the transformation from human to bat.

Produced in Jingdezhen, a city in China’s Jiangxi province with over 1,000 years of porcelain-making history, the tiles are displayed within customised pine wood frames with bat motifs, which reference Qing dynasty architecture and furniture.

In the future, Ng and Bisenieks are hoping to embark on a new ethnographic research endeavour in Lantau, but their interest in bats remains fervent, given the animals’ intriguing characteristics, social behaviours and cultural relevance. After all, even if bats may have gotten a bad reputation from Covid-19, they are still a symbol of good luck in Chinese culture.

“[Our work] became kind of somewhat of an advocacy for bats,” Bisenieks says. “We need to remember how important they are for our environments. If anything, they are a blessing, they are good luck. We need them.”

“Zheng Mahler: What is it like to be a (virtual) bat?”, PHD Group (near Bowrington Bridge, Causeway Bay), Wed-Sat, 1pm-6pm. By appointment only. Until Nov 11.