Ironically, the first staging, in Moscow in 1877, was a failure, and it was not until Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov created a new version in St Petersburg in 1895 that the ballet came into its own.

Today everyone has heard of Swan Lake, but few may realise that much of the original choreography is not always used.

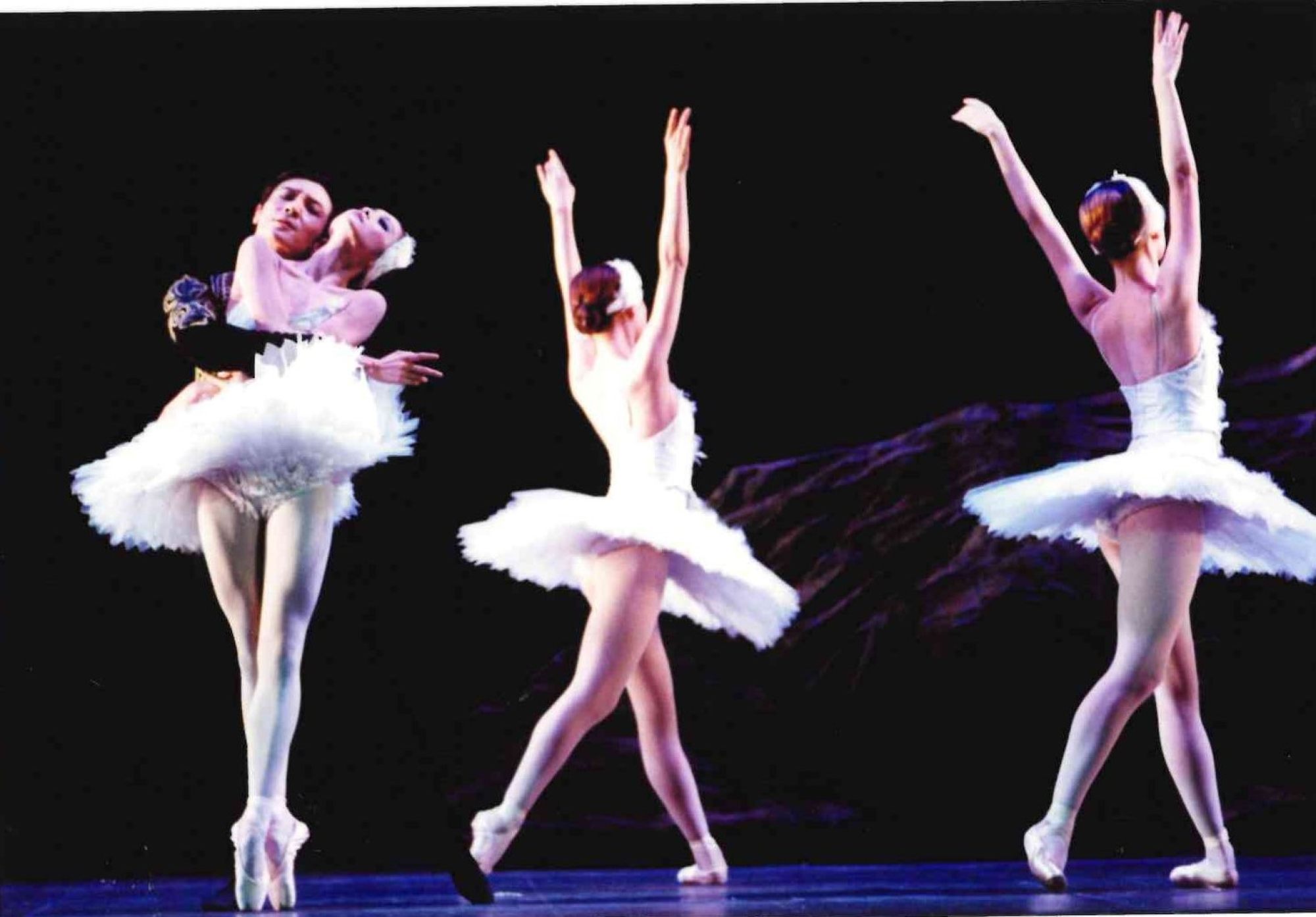

While the sections that have made it so iconic – Ivanov’s Act 2, where Siegfried meets Odette, and Petipa’s Black Swan pas de deux in Act 3 – are invariably included, the rest of the ballet can vary considerably from one production to another.

This will be the Hong Kong troupe’s fourth full-length staging of the ballet since the company was founded in 1979, and each production has reflected not only its artistic growth but the ideas of successive artistic directors.

The first, created by André Prokovsky in 1988 under Garry Trinder, was a necessarily modest affair given the resources available at the time.

Stella Lau, now senior lecturer of ballet at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (APA), was just starting her career as a dancer and recalls being one of the famous four cygnets.

“We had 16 swans in the corps de ballet, using students from the APA as we didn’t have enough professional dancers,” she says.

In 1996, when Stephen Jefferies became artistic director, his first full-length classical production was a new Swan Lake. By then the company was bigger and more technically accomplished, and he felt it was time for a version that would challenge and develop the dancers.

He also had a clear concept of what he wanted in terms of sets and costumes and worked closely with leading designer Peter Farmer to create a “sumptuous” setting.

His aim was a Swan Lake that would be “very classic, no quirks, well-drilled dancing, beautiful to look at and dramatic”.

In 2007 his successor, John Meehan, created another new production, keeping Farmer’s designs but commissioning two promising talents from the company, Carlo Pacis and Selina Chau, to choreograph Act 1 and Act 3 respectively, while Meehan himself did Act 4; a pas de quatre in Act 1 replaced the Petipa pas de trois from the Jefferies version.

In 2007 his successor, John Meehan, created another new production, keeping Farmer’s designs but commissioning two promising talents from the company, Carlo Pacis and Selina Chau, to choreograph Act 1 and Act 3 respectively, while Meehan himself created Act 4, and a pas de quatre in Act 1 which replaced the Petipa pas de trois from the Jefferies version.

Overall, the production was essentially traditional, apart from Chau’s new approach to Act 3, in which the princesses from whom Siegfried is supposed to choose a bride lead their country’s dances instead of having their entourages perform them.

The Meehan production continued to be performed until 2019, although Madeleine Onne, the Ballet’s artistic head from 2009 to 2017, did bring in a different Act 3 in 2014 as part of a triple bill to celebrate the troupe’s 35th anniversary.

Along with The Nutcracker, Swan Lake is undoubtedly the biggest brand name in classical ballet, guaranteed to sell tickets. So what made Webre decide the company needed a new Swan Lake?

The previous productions were “beautiful, but quite standard”, says Webre, and it’s difficult for a company of 50 dancers (even with extras brought in) to compete with the grand scale and unanimity of the corps de ballet productions by companies like the National Ballet of China and Shanghai Ballet.

For context, medium-sized companies like the Hong Kong Ballet usually have around 70 dancers. National companies have a lot more. The National Ballet of China has 109 dancers plus a reserve troupe. The Bolshoi Ballet has more than 200.

So rather than stay in the same lane as those giants, Webre wanted something that had a unique point of view, but also retained the work’s classical identity.

He invited Possokhov, a former principal dancer with the Bolshoi Ballet and now choreographer in residence at San Francisco Ballet, to create a new production for three reasons: his understanding of the ballet from a Russian perspective; his outstanding choreography – “intricate, classical but with a fresh point of view” – that would “do justice to the possibilities of that glorious music”; and “the psychology of the story”.

For any classical company, Swan Lake is an essential benchmark by which the standard of its dancing will be judged, says the company’s ballet master, Yuh Egami.

“It really shows where the company is, because it includes roles which give the whole hierarchy of dancers the chance to shine,” he says. The challenges are to deliver “excellence of classical technique” and a story that seems simple but must be “acted and expressed so that it will resonate with the audience”.

An added challenge for him has been rehearsing the dancers in Possokhov’s choreography because, after years of restaging the Meehan version, “When I hear the music, that’s the choreography I see in my head – and the music edit is different as well. I have to keep making notes to keep track”!

However, as a choreographer himself, Egami is relishing working with Possokhov. “I can see that when he’s deciding on the steps, he’d rather go with something unique even if it’s not completely classical, to invent new tools through interaction with the dancers.

“He really lives the moment with the dancers … He’s creating a new ballet, rather than just ‘doing Swan Lake’.”

Hong Kong Ballet’s most senior ballerina, Ye Feifei, agrees. “We are working together step by step with Yuri, so you know what he is thinking, why he is making this, so that makes it more interesting and more exciting. I can do the steps and show more clearly what he is thinking, what I am thinking.”

Having danced the dual role of Odette/Odile many times over the years, she adds: “Every time I dance it, it’s different. Because of my age, my body, my thinking – and this time it’s special because it’s new choreography.”

Rapport with your partner is paramount for any ballerina – and it needs to be emotional as well as physical: good technical partnering skills are not enough “if inside there is less, you feel the story doesn’t go and you cannot show much more”.

Ye is thrilled to be dancing with guest artist Matthew Ball, a Royal Ballet principal dancer, who is famed for his heartfelt, naturalistic acting. “The way he gives back to me, it really inspires me and makes me want to dance.”

While Odette/Odile is the linchpin around which Swan Lake revolves, Ye emphasises that “one person can’t make the ballet good, it’s the whole company; even small roles, they can make the ballet work … It’s how you’re acting to them and how they give back to you.”

The part of Swan Lake that varies most, with no definitive text handed down, is the final act.

In Soviet Russia, the tragic dénouement was replaced by a happy ending where Siegfried, Odette and the swans defeat Von Rothbart (the People Triumphing over the Oppressor).

The Meehan production had a conventional ending, with Siegfried and Odette dying together and Von Rothbart also expiring, conquered by the power of love. Jefferies took a more unusual approach – the lovers die, but the swans then turn on Rothbart and trample him to death with their pointe shoes in a memorably gruesome image.

“He was such a horrible person,” Jefferies tells the Post with a chuckle. “I thought he deserved a really horrible death!”

At the time of writing, the new production was not finished and nobody (possibly even Possokhov himself) seemed to know how it will end, although happy ever after seems unlikely.

Will the gamble of giving Hong Kong audiences such a different Swan Lake pay off? Webre is quick to point out that, unlike radical re-imaginings by the likes of Matthew Bourne and Mats Ek, “it’s not a revolutionary Swan Lake, just a very inventive one”.

Ye notes that with every ballet “some people will like it, some won’t. I hope the audience likes it! And I hope they like the whole ballet, not only the traditional parts.”