“We also [wanted] those outside the country to watch it. Basically we want to reach as many people as possible.”

From the beginning, Pendatang was conceived to be distributed freely online – a space where the LPF has no authority – provided it could be made by achieving a fundraising goal.

Amir Muhammad, a book publisher, director and managing director of Kuman Pictures – a Kuala Lumpur-based, genre-film-focused independent film company – set out to raise US$70,700 by October 6, 2022. A week before the deadline, the project’s Indiegogo campaign covered only 49 per cent of Amir’s target.

First Chinese-language film directed by a Malay woman

First Chinese-language film directed by a Malay woman

“When only seven days before we had not reached even half [of the sum], I didn’t want to put too much hope [in it] but also didn’t want to give up,” Amir says.

“We exceeded the target thanks to a last-minute push by an influential person in a WhatsApp group, proving how Malaysians are last-minute [people]. We are also grateful that [Malaysian film production company] Sunstrong Entertainment contributed the biggest amount even though they knew there would be no returns.”

Meeting the target meant shooting would start at the end of 2022.

“Our initial release date was in August 2023, but we needed more time for post-production, hence this December release,” Ng says. “Maybe it will make a good holiday film to watch with families and friends.”

Written by Lim Boon Siang, Pendatang – which means “immigrant” in Malay and is used mainly in daily life to refer to foreign members of the immigrant workforce – will undoubtedly make for a twisted holiday season watch.

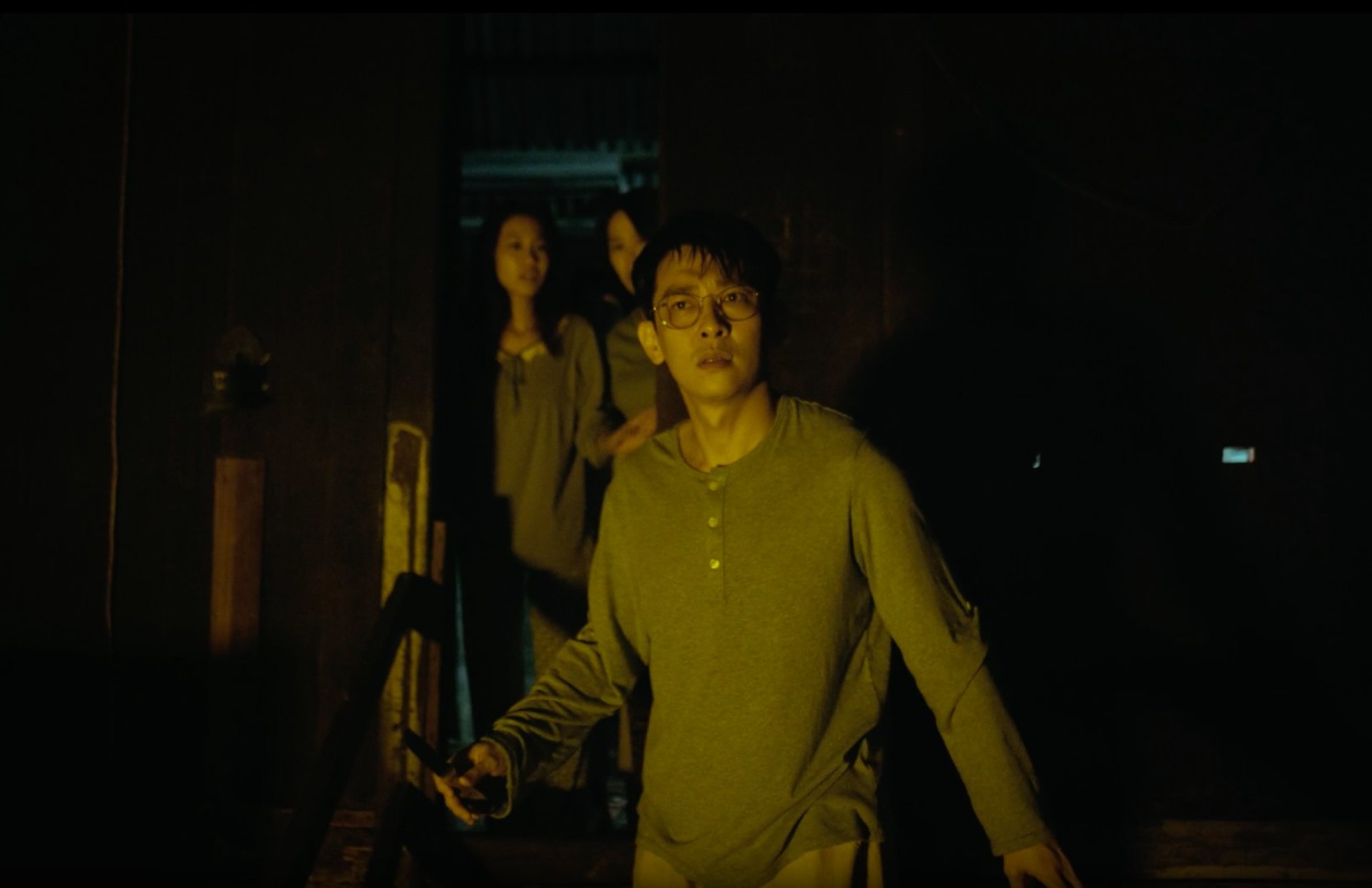

The film is set in a future Malaysia where a Segregation Act divides ethnic groups into tightly separated and controlled areas. Armed patrols distribute food rations and impose a daily curfew from 8pm to 8am.

It opens with the Wongs, a Chinese-Malaysian family of four, discovering to their dismay that they are to be relocated to a Malay wooden house in the countryside after a traffic offence. The father is confused as to why his Chinese family must take up residence in a former home of their racial enemies.

Because those who are found guilty of mingling with other races risk 25 years’ imprisonment, the Wongs don’t know what to do when noises in the attic turn out to be a lost young Malay girl.

Should the family report and surrender the non-Chinese intruder to the brutal military led by the violent general Ho, or should they hide the child away, saving her life but risking their own?

“What we are trying to say is that race is really only a skin-deep notion. Deep down, we are all just humans,” Ng says.

“To be honest, I think the [Malaysian] people are also tired of this card being used over and over again, where in fact the majority of us have no issues with one another.

“The success of [Pendatang’s] campaign suggests that [our] people are progressing beyond the rhetoric. And since we are releasing the film online, we do not need LPF’s approval.”

Malaysia’s censorship body can be unpredictable when it comes to local films.

Nell Eu published an apology on her social media, saying it frustrated her that her film’s primary audience, Malaysians, could not see the actual work she made and that won awards.

This experiment has worked out well for us and we hope others will try this platform if the project is suitable

Even films that are reserved for the online and streaming markets – and hence are technically safe from the LPF’s scissors – have got into trouble of late.

Khairi’s film tells the story of a girl who researches the world’s different religions to find out about life after death in response to losing her mother to a deadly sickness. Khairi is now challenging the ban in Malaysia’s High Court, with a first bid to commence judicial review set for January 31, 2024.

“It very much depends on who is on the board at that time and what sort of pressure they seem to be facing,” Amir says.

“I don’t think like a censor and am glad I don’t. But anything is possible. [But] Malaysians are very resourceful in finding ways to watch things that have been online anyway. They say the internet is forever.”

Regardless of potential future backlashes, Pendatang proves that even in Southeast Asian societies, where artistic freedom is often curtailed to defend conservative values, resourceful filmmakers can find ways to have their voices heard and films seen, regardless of budgets.

Considering its shoestring budget, Pendatang is exceptionally well-made and compelling.

“This experiment has worked out well for us and we hope others will try this platform if the project is suitable,” Ng says.

“Different films require different ways to get them made, so this is another option for filmmakers to consider.”

Amir has had several of his documentary films banned in Malaysia, including The Big Durian (2003) and The Last Communist (2006), and yet has kept promoting and publishing pulp fiction and films.

“Here and now, there are films to be made,” he says. “If you are a filmmaker who believes in a film, you just have to make that film.”