Retail brands like H&M, The Gap and Nike have gone to great lengths to satisfy growing consumer demand for sustainable clothing, but many of the companies’ labels and claims do not stand up to scrutiny, particularly when it comes to recycled materials.

CBC’s Marketplace found a number of products labelled as recycled or made with recycled materials selling at top Canadian retailers in the Toronto area. The items, purchased from H&M, The Gap, Zara, Nike and Lululemon, were available in-store and online across the country.

While clever marketing may lead consumers to believe their new shoes or clothes are made entirely from old ones, that’s simply not the case, says George Harding-Rolls, advocacy director for Eco-Age, a U.K.-based sustainability agency.

“We’re awash in a sea of green claims that are incredibly difficult to decipher,” said Harding-Rolls. In a report for the Changing Markets Foundation called Synthetic Anonymous, he reviewed some 4,000 products from 12 online brands and found that 59 per cent of green claims are unsubstantiated or misleading. Many of those claims were tied to recycled polyester.

One example Marketplace found was a pair of Nike sneakers labelled with its circular “Next to Nature” swoosh logo, which the company described online as made with sustainable materials with “at least 20 per cent recycled content by weight.”

Harding-Rolls says the shoes are “about as far away from nature as it’s possible to get.”

-

Watch the full Marketplace episode, Exposing the Secrets of Sustainable Fashion, Friday at 8 p.m., 8:30 p.m. in Newfoundland, on CBC-TV and anytime on CBC Gem.

While they might be a slightly greener choice for the planet, he says a new pair of sneakers is anything but sustainable, because despite being made with a small amount of recycled material, they are destined for the landfill once a consumer is done with them.

Harding-Rolls was also critical of a black-and-white Nike basketball jersey Marketplace picked up. It had what Harding-Rolls described as “a natural-looking” hang tag, “but then the item that it’s attached to is 100 per cent oil and gas — plastic, fossil fuel fashion.”

Nike did not respond to Marketplace‘s questions about its sustainability claims, or the number of environmental commitments it has made. The company referred us to its websites.

The problem with poly

Consumers are increasingly looking for sustainable solutions when they shop. Online searches for sustainable fashion in Canada rose by 37 per cent in the first few months of 2020 compared to the same period just a year before, according to U.K.-based fashion technology company Lyst.

Experts say less than one per cent of the world’s fashion waste is currently recycled in the truest sense of the word and almost all of the recycled polyester fashion brands use is made from old plastic bottles.

Polyester is a popular choice of clothing manufacturers. Recycled polyester is cheaper than virgin polyester, which is part of what makes it more attractive to fashion brands.

While recycled polyester does have a slightly smaller carbon footprint than its virgin counterpart, Harding-Rolls warns that recycled polyester — or rPet, as it’s commonly called — is not the saving grace some fashion brands suggest it is.

“If you’re using plastic bottles, you’re actually taking bottles out of a potentially closed-loop recycling system, and then giving them a one-way ticket to a landfill disposal,” he said.

For this reason, Harding-Rolls also took issue with The Gap’s 100% recycled Maternity puffer jacket, which Marketplace found selling online alongside the words “Less waste in the world. More great clothes for you.”

While the name implies the jacket itself was recycled, that simply isn’t the case. The shell is recycled polyester, while the lining is a 100 per cent nylon and the fill is 100 per cent polyester — both new materials.

In an email, Gap INC. told Marketplace the company “may seek to highlight credible and verifiable sustainability attributes of some of the products in their assortment.”

Gap admitted it needs to do more to reduce its environmental impact, saying it is “committed to partnering with relevant stakeholders on these issues.”

Harding-Rolls believes most people have no idea that plastic is made from fossil fuels, “let alone that plastic is getting into their clothing and it’s made from the same kind of oil and gas feedstock.”

The difficulty of recycling

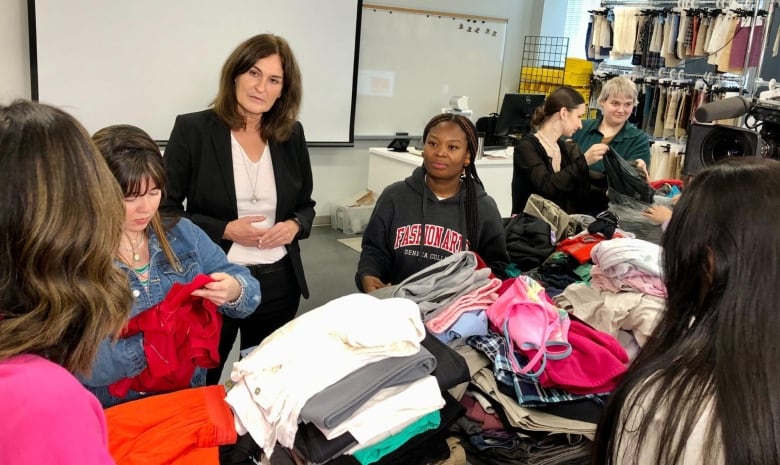

Sabine Weber, a professor who specializes in textiles at the school of fashion at Seneca College in Toronto, isn’t buying the circularity spin many fast fashion brands are pushing when it comes to promoting items made with recycled material or labelled as recycled.

The problem, she says, “is that people think, oh, we can consume and continue consuming and then when we are done we can actually recycle it — so it’s a bit misleading.”

Weber’s research found that Canadians generate about 500 million kilograms of textile waste every year, and a significant amount of that is finding its way to landfill. As part of her 2020 analysis of Ontario’s residential waste, Weber also found textiles to make up over four per cent of the residential waste stream.

She says that when it comes to taking our old clothes and turning them into new ones — or recycling in the way most consumers think of it — brands are still in the very early stages.

That’s because “recycling is a lot of work, very labour-intensive and you need to have the right technology,” said Weber.

Part of the challenge, she explains, is that much of what we wear is made up of blended fibres, and in order to recycle these garments, you have to separate them.

Take a cotton-polyester-blend T-shirt, for example. In order to turn that old shirt into a new one, and truly recycle it, you have to put it through a chemical process. That process, known as textile-to-textile recycling, is still a fairly new technology.

“Globally, there is a race among companies trying to develop recycling processes for fibre-to-fibre recycling, but we have very little scale,” said Weber.

While progress is being made, it’s not happening nearly as fast as it needs to in order to make a dent in the fashion waste we continue to create, argues Weber. “We have to set … the bar really high of what we should purchase.”

Problems beyond polyester

Products made from recycled polyester weren’t the only items that drew criticism from experts as part of Marketplace‘s review of so-called sustainable hang tags.

Wren Montgomery, a business professor at the Ivey Business School in London, Ont., pointed to several of what she calls “textbook examples” of greenwashing across the products Marketplace purchased.

A pair of shorts from Lululemon included a tag that lists the lining of the pockets as 100 per cent recycled polyester but the body of the shorts as 95 per cent nylon and five per cent elastane.

Montgomery calls it a classic “shiny toy” example of greenwashing, when a company chooses to give marketing attention to a very small portion of a product as a means of distracting consumers from overall impact.

“I am generally not very confident that a product or company is sustainable when their marketing is heavily reliant on vague and confusing claims. If you are really walking the walk, why would you waste so much time on empty talk?” Montgomery said.

In an email, Lululemon told Marketplace the company is on a journey to make products that are better in every way, and that they “recognize there are areas where we need to accelerate, and we continue to engage in industry collaborations to find collective solutions.”

At an H&M in Toronto, Marketplace found a two-pack of sweatpants labelled “Conscious” with additional green-coloured hang tags labelled “Conscious Choice.”

Interestingly, the company has removed those terms from its websites around the globe following a 2022 greenwashing investigation in the Netherlands. The Authority for Consumers and Markets there condemned the company’s use of the terms “conscious” and “conscious choice” for failing to explain what they actually mean. It also found that the explanation of the sustainability benefits for specific products was “lacking.”

H&M subsequently agreed to adjust or stop using sustainability claims on its clothing and all of its websites. But when Marketplace went shopping at H&M in Toronto, products featuring those labels and claims were still widely available.

In emails, H&M told Marketplace it is phasing out those hang tags from all locations, including Canada, but acknowledged it will take some time before they are gone from store shelves.

H&M explained that at present, approximately one of every five of its products is made of polyester. But the company plans to transition “on scaling textile-to-textile recycling for synthetics.”

Montgomery also singled out a pair of women’s jeans at Zara. She described the hang tag as using appealing imagery such as bees and clouds along with positive phrases about the world, which included “supporting the creation of ecologically grown crops” and “helps to preserve biodiversity.”

Montgomery points out that all crops could be considered ecologically grown and that “these seemed like very empty and vague statements with an unclear connection to the product and no apparent proof of what Zara is doing to back up all of these.”

Zara didn’t answer Marketplace‘s questions about that tag. In an email, the company referred CBC to its annual report, adding that “customers continue to be able to check all relevant information about the origin and composition of all our garments, including the information related to the sustainability of the fibers used.”

Zara also said it has committed to reducing its consumption of virgin synthetic fibres.

Montgomery admits it can be tough for Canadian consumers looking to make more environmentally friendly fashion choices.

“Greenwashing is far too prevalent and it is harming companies that are truly trying to make progress on sustainability. It is harming consumers who may pay more for products they believe are sustainable.”

With files from Katie Swyers