Its copper-coloured, environmentally friendly roof is peppered with photovoltaic components to maximise generation of renewable energy from sunlight. Below it stand multi-laminated transparent walls up to 16 metres (52 feet) high, constituting China’s first self-supporting glass facade, its zigzag, folded design meaning one piece bolsters the next.

As for that world-beating space, it’s no void. Norwegian architectural firm Snohetta, commissioned to design the library after winning an international competition in 2018, called it a “reading landscape” in early communiqués.

And although it would be a stretch to say a river runs through it, a pathway “stream” does meander across the valley floor, past trees growing out of a moat.

Up the valley sides are terraced “hills” of stepped seating recalling rice paddies; and gazing down on the whole ecosystem is a forest canopy of overlapping giant ginkgo leaves, in which the tops of glass-reinforced gypsum columns flare out, supporting the roof and draining rainwater for recycling. Real ginkgo trees have been planted outside.

The library’s overall sustainability quotient has earned it a Three-Star Green Building Evaluation Label, China’s highest ranking.

As designer – and Snohetta managing director for international projects – Robert Greenwood has described it, being inside the library is like “sitting under a tree reading a book”. Appropriate, given the generous use of solid white oak.

Greenwood, until recently based in Hong Kong, explains how the building’s nature-inspired, sinuous interior landscape suits the project parameters. Erected in Tongzhou, a “sub-centre” of the city to Beijing’s southeast, the library, which opened in late December, stands in what was an extensive post-industrial wasteland.

“When we started this project, which is a spin-off from the Capital Library of China, in Beijing, there was nothing there, just old factories being torn down,” he says. “The project was called the Green Heart, but it looked brown and industrial – a brownfield site.

“Now, it’s also a new administrative centre,” he says, “with some things moved out of central Beijing. They’re putting in a metro line and station, with some associated retail, but it’s very much a cultural district.

“There are three buildings: a performing arts centre, museum and library, all in one big park. It was a complicated competition, because it called for a master plan with those three. We were on the shortlist for all of them and happy to get the library.”

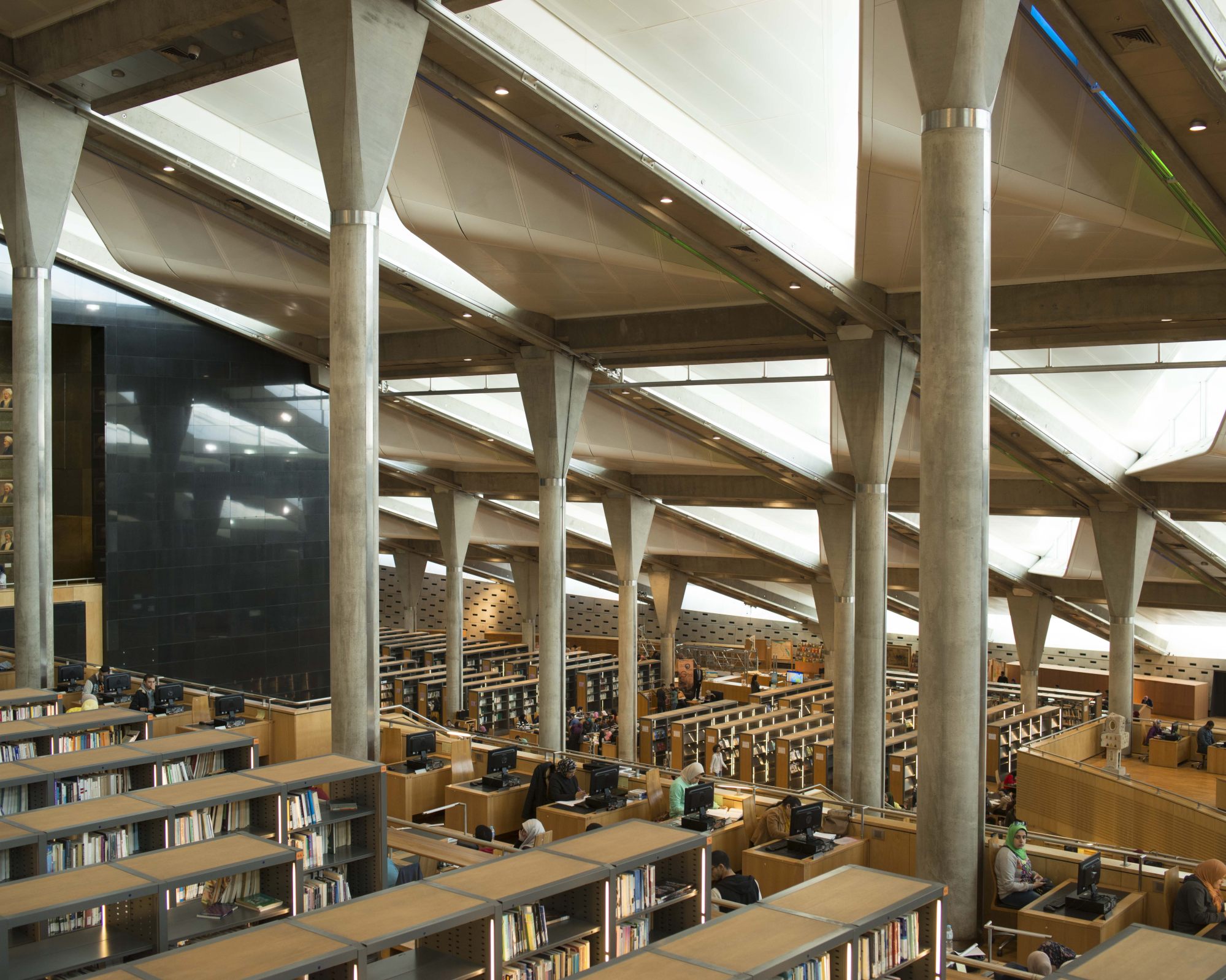

“Until we opened Beijing,” says Greenwood, “Alexandria was the biggest library space in the world and we were very proud of that – and in many ways it’s a development from Alexandria: the idea of the big space, the big room.”

With nine independent libraries and four integrated into a museum or campus now in the Snohetta portfolio, was it possible to design the Beijing City Library on a blank slate?

“I don’t think anything is from complete scratch,” says Greenwood. “I don’t think it’s possible. It’s not how the world works. In our minds, you are exposed to these things. You take with you what you think is relevant and what means something.

“We are always building on things we’ve thought of before – maybe you didn’t build, didn’t win, didn’t get the chance to build, but we’re taking those with us. We probably lost 10 library competitions before we won this one.”

Inside, the library is so vertiginous in parts that not all “paddies” are accessible. “We have to restrict where people can sit, because in places it’s really steep,” says Greenwood. The structure, covering 75,000 square metres, also contains work desks, open-access bookshelves, a basement storage area with book retrieval by robot, and audiovisual equipment rooms beneath the terraced “landscape”, within which are floor divisions.

As Greenwood puts it: “You go to a library not to go into a little room and study your one little book alone, but because other people are there. There are lots of books, but you can get all that information at home in front of a screen.

“You go to a library because you’re not alone. You’re alone with lots of other people,” he says. “And in this big space, everyone is under the same sky, the same canopy; we’re all there together.”

The library’s “acoustically treated” sound dampeners aside, isn’t it noisy in there? Isn’t the librarian constantly hissing, “Ssshhhhh …”?

“People aren’t making a lot of noise and dancing, but I think [going to the library] is definitely a social event,” says Greenwood. “It’s a place to meet.

“I used to study a lot in Liverpool Central Library (in northwest England) and that was a huge dome of a space. But the acoustics were such that if you dropped your pencil everybody would hear it. So you were extremely quiet, you didn’t rustle newspapers or anything like that.

“This is a very different space,” he says. “And as with Alexandria it isn’t a dead space acoustically. You’re surrounded by bookshelves, books, furniture; these things absorb some of the sound around you, but it has acoustic presence.

“It’s a little bit lively; that doesn’t make it noisy, it just means you’re in an acoustically alive space. I think that’s really important, being in a space where you can hear a bit of background noise, but not enough to be disturbing.”

“It’s an easy space to be in,” adds Greenwood. “You can relax. That’s probably not the worst thing.”