While such depictions largely mirrored the gender norms and roles of the time, they occasionally transcended these constraints.

And more importantly, they were an active, albeit much less known, force behind the production and advancement of Buddhist art itself – both as devout practitioners and influential patrons.

“Unsullied, Like a Lotus in Mud” at the Hoam Art Museum in Yongin, in South Korea’s Gyeonggi province, is a groundbreaking exhibition that, for the first time in the world, revisits centuries-old Buddhist art of Korea, China and Japan through the specific lens of gender.

“In ancient Buddhist paintings, our attention is often drawn to the splendid figures of the Buddha and bodhisattvas, shimmering in gold, exuding delicacy and dignity,” Lee Seung-hye, the show’s curator, explained in a recent press preview at the museum. “However, this show aims to highlight the presence of countless women beyond that golden brilliance.”

The exhibition features 92 treasured paintings, statues, scriptures and embroideries from 27 collections worldwide, making it an exceptionally rare event.

Got any of your pet’s fur to spare? This Hong Kong artist wants it

Got any of your pet’s fur to spare? This Hong Kong artist wants it

In fact, more than half of these artefacts – which hail from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, the Tokyo National Museum and the National Museum of Korea, among others – are being displayed in Korea for the first time.

The show also marks a brief yet remarkable homecoming of a seventh-century gilt-bronze standing Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva statue from the Baekje Kingdom (18BC-AD660). The 28cm-tall (11-inch) sculpture of an enlightened being with a mysterious smile was last seen in its homeland in 1929, before being taken to Japan by a collector.

In 2018, Korea’s Cultural Heritage Administration attempted to repatriate the relic for 4.2 billion won (US$3 million) but ultimately fell short of the owner’s demand for 15 billion won.

In many early texts, women were taught that they could not attain enlightenment through their bodies

The exhibition starts by exploring representations of women in traditional religious art. Historically, the Buddha and bodhisattvas have predominantly been depicted as male or as gender-transcending beings, limiting the portrayal of female subjects.

As human figures, they were often depicted fulfilling their expected familial roles – Queen Maya as the birth mother of the Buddha, Mahapajapati Gotami as his carer and Yasodhara as the grieving wife upon learning of his departure from palace life to pursue asceticism.

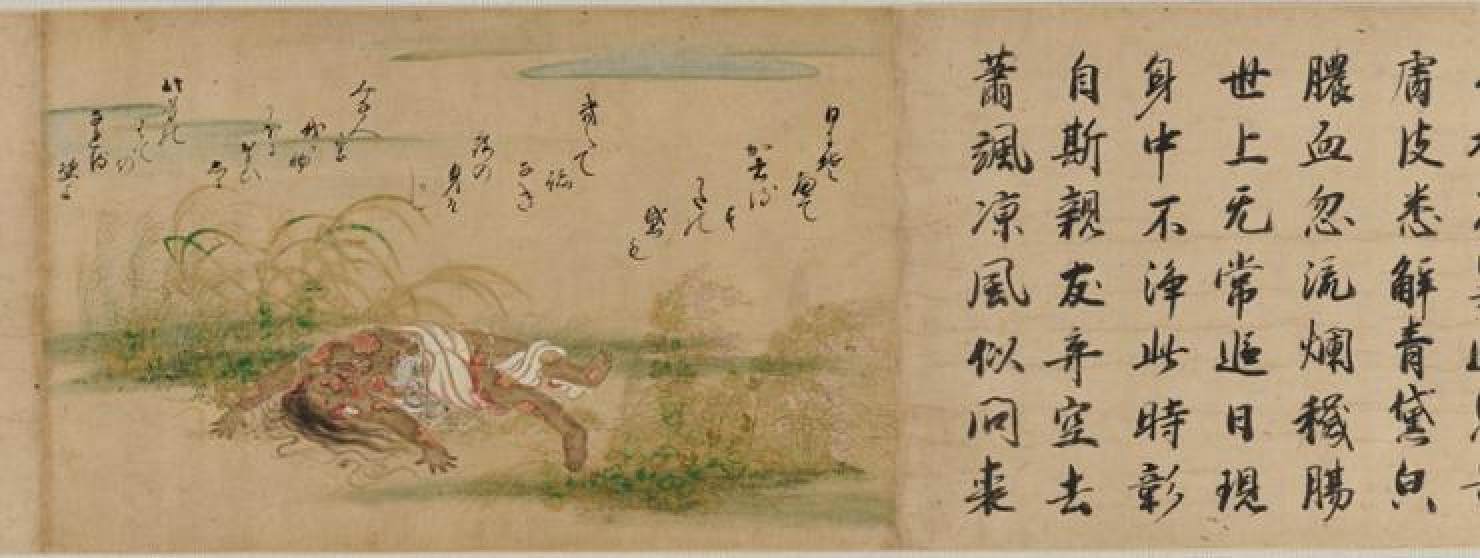

Women’s bodies were also regarded as symbols of impurity and sin, a perception vividly captured in artworks such as Nine Stages of a Decaying Corpse from Japan’s Muromachi period and Edo era.

These paintings originated from Buddhist meditative practices, where practitioners visualised or observed the gradual decomposition of a corpse to cleanse their minds of sensual desires. In most, if not all, cases, the bodies portrayed were young and beautiful, reduced to mere objects of contemplation for male viewers.

However, there were instances where women were represented as the holy bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokitesvara. Originally portrayed as male in India, he gradually assumed various guises over the centuries in East Asia, including manifestations as a female figure.

Through a series of portraits and statues, the show presents the bodhisattva in both male and female forms, including Water-moon Avalokitesvara, Thousand-armed and Thousand-eyed Avalokitesvara, Guanyin with a Fish Basket and Avalokitesvara, the Bringer of Sons.

Shanghai’s Art021 art fair to launch Hong Kong version in summer 2024

Shanghai’s Art021 art fair to launch Hong Kong version in summer 2024

The highlight of the exhibition is on the museum’s second floor, where the spotlight shines on the essential contribution of women as driving forces behind the advancement and flourishing of Buddhist art, both as patrons and artisans.

As devout followers of the faith, women sought spiritual attainment by commissioning illustrated manuscripts of the scriptures, as well as paintings and sculptures. Their roles as patrons are evident in dedication materials, particularly in votive inscriptions, sealed inside the relics.

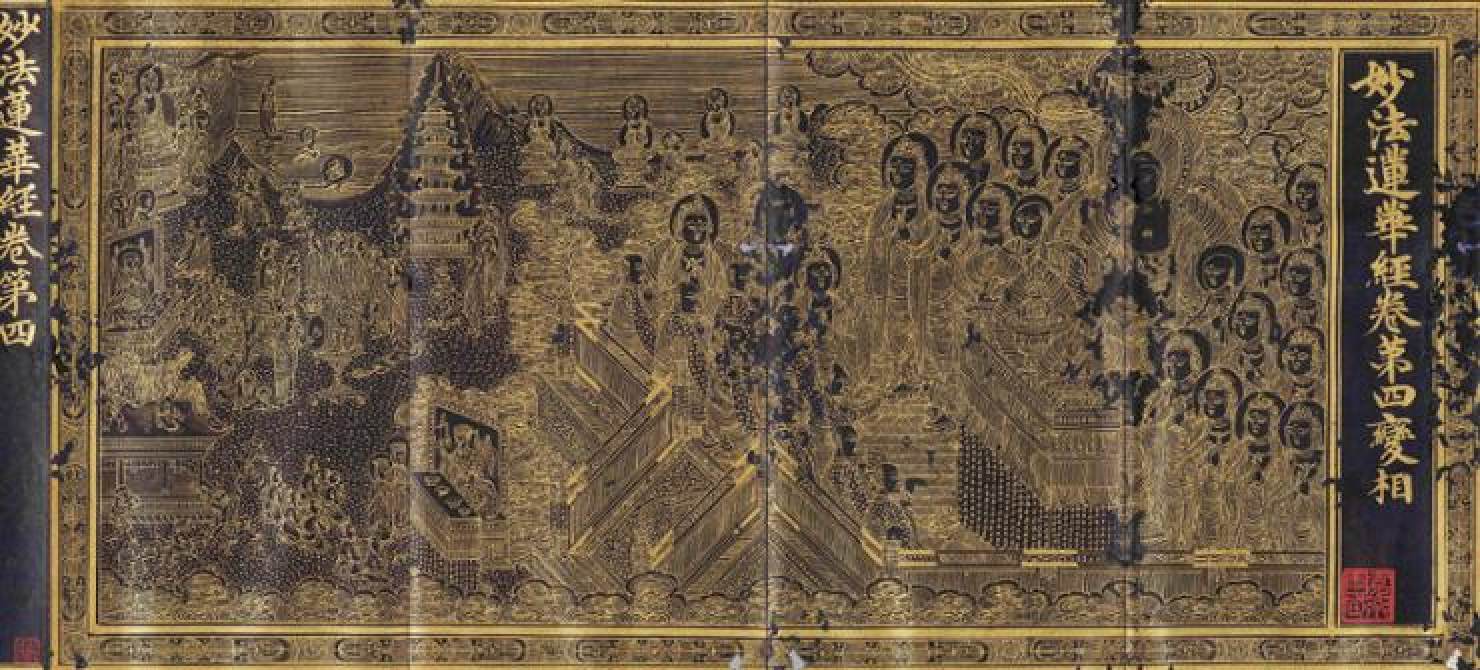

“For my past life’s misfortunes, I have been reborn as a woman … Therefore, with the deepest sincerity, I earnestly wished to create one copy of the ‘Avatamsaka Sutra’ written in silver and one copy of the ‘Lotus Sutra’ written in gold,” wrote an unknown noblewoman of the Goryeo era (918-1392) in her inscription as the commissioner of one such manuscript.

Somewhat ironically, other notable patrons of Buddhist art included queens, consorts and members of the royal court during the Joseon Kingdom (1392-1910), a period when the official policy was to suppress Buddhism in favour of neo-Confucianism. Their prominent patronage of religious art was viewed as an offering for the king’s longevity and the birth of sons.

Visitors can admire a series of magnificent paintings commissioned by Queen Munjeong (1501–65), the wife of King Jungjong and mother of King Myeongjong, all in one place. Among them is The Assembly on Vulture Peak, which renders the Buddha, bodhisattvas, arhats and heavenly spirits in delicate golden strokes against a backdrop of red-purple silk.

As creators, women, often unnamed and unrecognised, crafted intricate textiles and embroideries in dedication to their faith.

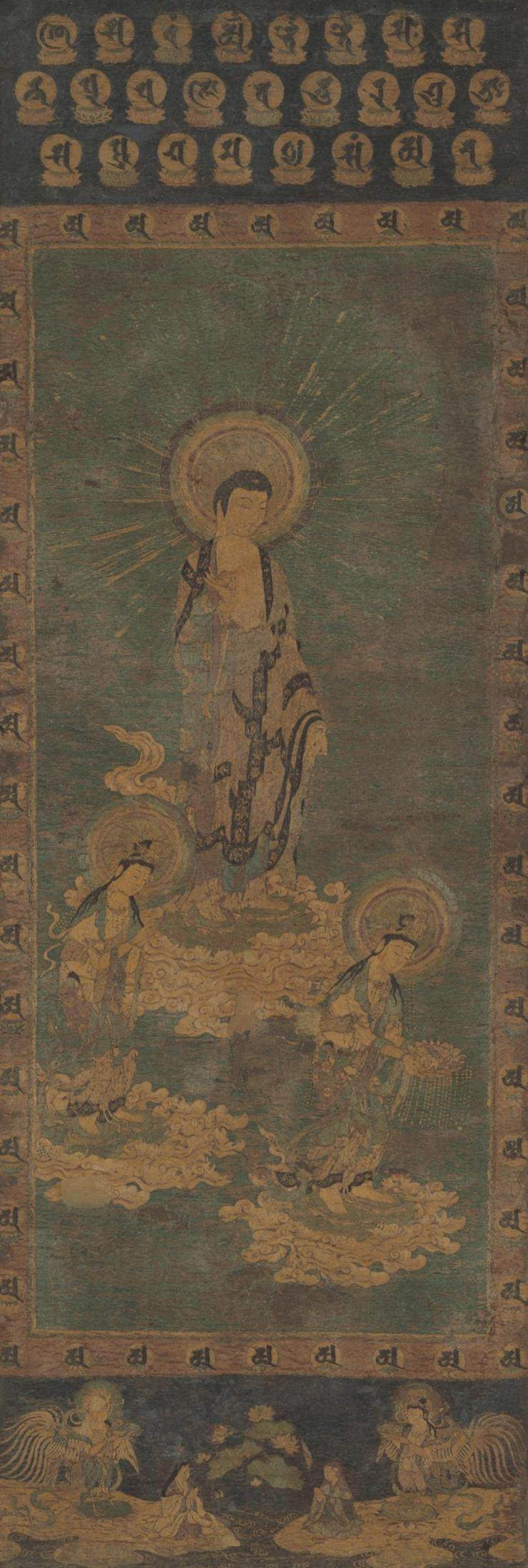

The medieval Japanese piece titled Welcoming Descent of Amitabha Buddha Triad stands out as the centrepiece of this section.

Its subject matter is a familiar one: the descent of the holy triad to welcome the recently deceased into the Pure Land. What makes it striking, however, is the use of real strands of hair to embroider Amitabha Buddha’s ringlet curls, the bodhisattvas’ hair and the Sanskrit syllable “A” – most likely sourced from the female artisans or patrons themselves.

“In many early texts, women were taught that they could not attain enlightenment through their bodies,” curator Lee said. “But, by using parts of their own ‘sinful’ bodies to portray the most sacred Buddha, these artists have achieved a remarkable creative transformation.”

Overall, the show offers a meaningful visual feast to relish and celebrate the legacy of women in an overlooked chapter of artistic history.

To ensure accessibility for a wider audience, a free shuttle service will run every Tuesday and Friday throughout the exhibition period, ferrying visitors between the Leeum Museum of Art in central Seoul and the Hoam Art Museum.

“Unsullied, Like a Lotus in Mud” runs through June 16.